By Tiago Nunes Ribeiro & Valentin Richoz

Abstract

In the following, we will focus on three ethnic shops in Lausanne, a very multicultural city. All the three shops use the migrants’ language (in our selection of shops: Russian, Spanish and Portuguese), as well as French and English. We will try to determine the reasons of the use of two or three languages. Some owners use language to reach a specific, migrant clientele and then propose foreign products to respond to its needs. Foreign languages on signs flag authenticity for migrants but also for locals or members of other communities. The staff is itself bilingual. They can then respond to the migrant clientele’s needs but also to those of the local clientele. Indeed, those shops also propose usual products, not necessarily culturally marked, to respond to the basics needs of the district on which the shops are inserted inhabitants who comes from many different countries. Furthermore, the authenticity of ethnicity conducted by language on signs can attract both migrant and native customers attracted by the foreign. We also noticed a particular use of French and English as linguas francas on regulatory signs. Finally, if it is recognised that the owners use their first language or mother tongue for advertising purposes, oriented both towards migrant and native customers, some admit that “it works that way”, it was not their purpose when putting the signs.

Introduction

Many migrants open shops in their host country, proposing products linked to their cultures and imported from their countries of origin. Our main research question in this project regards the use of migrant languages on those shops’ signs, especially in three ethnic shops located in the centre of Lausanne: Doushka, a Russian shop in Maupas Street, La Tienda de la Esquina, a Latino and Casa Graça, a Portuguese shop, both in the Riponne/Tunnel district. Lausanne is indeed a very multicultural city, where about 43% of the population do not have the Swiss nationality, according to the Contrôle des habitants[1]. We suggest that some owners use language to reach a specific, migrant clientele and then propose foreign products to respond to its needs. According to our questioning of the staff, they seem to be bilingual (in French and their mother tongue) in all the participating establishments, thus being able to better respond not only to the migrant clientele’s needs but also, to those of the local clients. Yet, foreign languages on the signs are used for commercial purposes. They flag authenticity for both migrant and native customers, thus attracting them both.

Our research follows the research that Maria Sabaté i Dalmau did on locutorios in Catalonia, Bernardino Tavares did on Cape Verdean shops and restaurants in Luxembourg, and Michael Parzer, Franz Astleithner, and Irene Rieder did on native Austrians’ use of immigrants’ groceries.

We first took pictures of the multilingual signs on the exterior of the shops and then interviewed the owners or some staff members about their use of multilingual signs. In the paper, we will present and discuss both the pictures and the interviews, after having introduced more precisely the three studies presented above and some linguistic concepts used, as given some contextual and methodological information.

Theoretical Framework

In her article Maria Sabaté i Dalmau suggests that, in the domain of mobile phones in Spain, ethnic mobile operators and multinationals that can propose formulas that specifically aim at a migrant clientele only use their languages as a marketing tool. Migrants’ languages are used in advertisements, but the workers do not necessarily speak the language of the migrants at whom they aim through the advertisements. Those ones are sometimes translated via generic automatic translations, usually providing an incorrect translation. Only locutorios (call-shops) provide a satisfying response to migrants’ needs, by proposing services in the migrants’ languages. They are “ethnic businesses run by and for migrants in urban localities”. Their huge success can be explained by the social infrastructure they provide, that usually goes beyond the only needs for accessing technology. Thus, they can overcome and subvert the linguistic and legal regimes imposed by the state to observe and restrict immigration. That subversive dimension should be less observed in the Swiss context because no law forbids the use of non-Swiss languages in advertisements. Thus, we may expect that Lausanne’s ethnic shops are not only used by migrants but also by natives.

In “The point of arrival: Cape Verdean spaces in Luxembourg”, Bernardino Tavares also remarked that migrant shops and restaurants are not only a way to earn money. The migrants’ enterprises he studied are also a way to maintain transnational ties. In Luxembourg, the Épicerie Créole, a Cape Verdean shop, even gained the status of an informal embassy because they propose different services such as promoting cultural events, engaging in some solidarity campaigns, or advertising some jobs. For many Cape Verdeans, the shop is closer than the official embassy and the relationship with the staff is less formal than with the embassy’s workers. Obviously, the shop’s staff is trilingual. Creole and Portuguese are spoken in Cape Verde and are then the migrants’ languages. French is finally used as a lingua franca with other customers. In theory, the Luxembourgish context is closer to the Swiss one, even if we would not dare to call Lausanne’s shops “informal embassies”, though the idea to maintain transnational ties is still very present as our research may show.

Finally, Michael Parzer, Franz Astleithner, and Irene Rieder brought another interesting perspective in “Deliciously Exotic? Immigrant Grocery Shops and Their Non-Migrant Clientele”. They studied the native Austrians’ use of immigrant groceries. They propose two different modes of shopping, usually represented by two types of customers. The “consuming for convenience” mode is often motivated by reasons of practicability (e.g. closeness) and linked with the “Nevertheless-consumer”. They use migrants’ shops routinely, “in spite of the migrant background”, what risks to lead to xenophobia, at least according to the authors and their observations. We find their position too radical on that point. The “Nevertheless-consumer” could be totally delighted by an immigrant grocery, even if its frequentation is mainly motivated by reasons of practicability. The second mode is “consuming for exceptionality” and is linked to the “Because-consumers”. These ones are attracted by the “foreign”, and thus choose ethnic shops because of ethnicity. In contrast, they risk engaging and reproducing ethnic stereotypes. The authors also argue that their findings challenge some previously believed statements where arguments pointed towards natives shopping routines in immigrant stores become increasingly ordinary.

There are still some important notions that will occur in our own body of work that have to be defined previously. The difference between monologic (monolingual regimes) and dialogic regimes (multiple regimes in one place) regarding space (Blommaert, Collins and Slembrouck, 2005). Also, the deictic nature of the signs, explaining how they take a major part of their meaning from how and where they are placed is considered within this theme. The production of signs is analysed through the notions of top-down and bottom-up: the first one is produced by the government, local councils or the owner of a site, thus mainly displayed in official languages, and the latter is produced by individuals or small groups, consequently in non-official language. Furthermore, different types of signs will be discussed and these are divided into four types: regulatory discourses (traffic signs or other signs indicating official/legal prohibitions), infrastructural discourses (directed to those who maintain the infrastructure or to label things for the public), commercial discourses (advertising and related signage) and transgressive discourses (a sign that intentionally or accidentally violates the conventional semiotics at that place such as the discarded snack food wrapper or graffiti, any sign in the “wrong place” (Mooney and Evans, 2015: 92).

Contextualisation

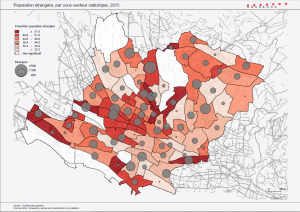

We focus on three ethnic businesses, but there are many more in Lausanne. Indeed, that city, which is the fourth biggest of the country, is a very multicultural city. For an increase of less than 20 thousand people residing in Lausanne since 1981, the foreign population has almost doubled, reaching 42.98% in 2017, according to the Contrôle des habitants. Such a proportion of foreigners logically encourages the opening of ethnic businesses. In Lausanne, 15.52% of the foreigners are Portuguese (6.67% of Lausanne’s population), 8.16% are Spanish (3.51% of Lausanne’s population), and finally 0.93% are Russian (0.40% of Lausanne’s population). Portuguese and Spanish people are respectively the second and third foreign population, after French. Furthermore, there is no ghetto, Chinatown, or similar type of districts that would enclose reunite foreigners only in some areas. Every district is multicultural, though the repartition of Swiss and foreign people is not totally uniform, as the following map shows.

The three shops we analyse dwell in Maupas Street (Dousika), at the Tunnel place (La Tienda de la Esquina) and close to the Riponne place (Casa Graça). There are 45.35% of foreigners in Maupas District, including 1.16% who come from Eastern Europe (0.53% of Maupas’ population). In the Tunnel/Riponne District, there are 60.66 %? of foreigners, including 47.50% of people coming from South Europe and 11.08% from Central or South America. It is the second district in terms of proportion of people coming from those regions. Unfortunately, the Contrôle des habitants does not divide in countries, but in regions. It is hard to know the proportion of Portuguese among people coming from South Europe, for example. Those numbers are then difficult to use but give an idea of the proportions.

Methodology

We first looked for shops using multilingual signs on their shop windows and took some pictures of them. Then, we analysed the way they use the different languages. For some only the name is in the migrant’s language, while others use French or English as lingua franca. Finally, we interviewed the owners or some employees to get some information about the reason of using different languages and about the kind of clientele they have.

What we learnt thanks to these interviews is that some owners chose to use their mother tongue as a cultural distinction, but without any real commercial purpose. It is once the shop opened, that language works as advertisement, though involuntarily.

Results

To discuss our findings, we firstly looked at our pictures and described them from a linguistic point of view. Firstly, the majority of the signs placed are top down; within this category we find signs giving the name of the place as well as their slogan or other precisions such as the kind of service provided. Bottom-up signs are visible in the Latino and Portuguese shops as a manner to provide punctual information (such as a concert) or some legal information, as it can be seen in the Portuguese’s shop window.

Regarding the type of presented signs, they are mainly of the commercial discourse type, although in the Portuguese shop vitrine, we can find regulatory signs addressing purchase and consumption of alcoholic beverages. To address language itself, we have separated the different occurrences of each language to provide a more visual aspect to the numbers, or in other words, a quantitative analysis, so we can get an idea of what language(s) rule(s) the other(s):

Language No of occurrences %

English 3 12.5

French 11 45.8

German 1 4.16

Portuguese 1 4.16

Russian 1 4.16

Spanish 7 29.1

A qualitative analysis seems to establish a certain hierarchy of the different languages in contact where French seems to be on top. This is due to address not only a native audience, but also people of a foreign heritage that may not master the language and is mostly present on Doushka’s window. In La tienda’s case, only the welcome sign is in French (along with events posters), which reinforces our idea that it serves as a way to tie a bond with native customers.

.

Also, English appears on 12.5% of the signs but mainly as a language of trade and a certain prestige as it can be seen in the shop window of the Portuguese shop, where the language informs people that the business is protected by a security company but is meaningless in a business point of view as it is not directed to customers.

Discussion

We can say that we have found what we expected, even though the articles we read to prepare this work not always pointed towards this direction. We initially thought that these commercial places were not only targeting an immigrant community but also the native community because they provide services found in any other kiosk or commercial surface in addition to the foreign products, thus all people around these places would turn to them in case of need. The fact that these places are situated on places that, according to official statistics, have a high foreign community also contributed to our opinion that these places are frequented by people of all national backgrounds. According to the interviews we made, this is the case: although a majority of clients share, as to be expected, the same national background and represent a majority of all three shops visitors, owners witness the surfacing of a minority constituted of native customers and from various other ethnic backgrounds. That is suggested in Parzer, Astleithner, and Rieder’s article and confirmed by the presence of certain clients on the store at the time of the interviews.

As expected, French takes a major place in the disposition of the different signs as we are in an area where it is its main/official language, so, in order to attract such clients, business owners must also address them, and this is common to all of the three shops. The business less in contact with its roots is Doushka as its native language, Russian, only appears once in the bottom of their vitrine. This is, once again, to show how much importance they give to the natives but also, partly because the Russian population in Lausanne is rather limited as shown with the Ville de Lausanne’s statistics. In comparison, Casa Graça and Tienda de la Esquina face a larger immigrant audience (Portuguese and Spanish-speaking) and as such, the presence of foreign languages with business purposes are far more popular with French being, once again, a means of appealing to native clients. Additionally, in both cases, publicity to events appealing to all communities appear (such as a circus, some concerts) thus showing a will of integration in the local culture. Events proper to their communities also appear, thus joining the point made by Tavares’ research where these places are a place of gathering for people of the same ethnic and/or linguistic background.

Lastly, the use of French as a lingua franca (as suggested by the proportion of French in the shop’s windows) is noted. By using this language, the window becomes appealing and understandable to all in the surroundings, thus making these businesses truly remarkable by the variety of the clientele. To be noted, is the word Epicerie, in French although the rest of La tienda’s vitrine is in Spanish once again highlighting the importance of the “Nevertheless-consumer”.

As previously stated, English is seen in one instance, as a publicity to a security company. Although it could be interesting to add English to this already big bouquet of languages, in this particular case, it is irrelevant to our research. Indeed, the security company uses it as a lingua franca but it is required to visibly mark their intervention zones. The sign is in no way directed towards the clientele (or at least the honest one); the presence of this sticker has a dissuasive role on potential robbers.

There is a last important element for our research which was revealed thanks to the interviews. The shop tenants are unable to explain their choice regarding what is displayed in the windows, and more specifically, the languages (except, in our case, to the Russian business which specifically wanted a simple vitrine that reflected their affiliation). Although they willingly make publicity to some events in the nearby area. It comes across as accepting to be a kind of relay for these kind of events, thus highlighting and affirming the business’ culture and specificity. The commercial character of the multilingualism found in these businesses would be, then, unintentional. The tenants do not make a clear effort to maintain transnational ties beyond the strict foreign products they sell in their shops.

Conclusion

We finally discovered that shop owners do not necessarily mean to use migrant languages, namely Spanish, Russian and Portuguese, for commercial purposes, though it involuntarily and indubitably gains a commercial issue, as advertisement. The owners propose both cultural products and generic products to attract any close inhabitant. Thus, French is used as a lingua franca not only by the staff who needs to answer in both languages (French and their mother tongue), but also on the signs to attract and prove to natives or migrants from other places that the shop is also designed to respond to their needs. If owners want to propose to the migrants some products that will help them to keep a transnational tie with their origins, their purpose seems to be mainly motivated by the only wish to open a shop, and the association to their origins seems to occur very naturally.

Finally, such a research must be more exhaustive by enlarging its panel of shops analysed. Not only improvement in number can be done, but also some gatherings in districts or regarding the origins of the owners and staffs. Indeed, we could make comparisons between the way Spanish, Portuguese, and other migrants use languages. Maybe the tendencies change according to the origins or to the place where the shops are located.

References

Blommaert, Jan & Collins, James & Slembrouck, Stef. (2005). Spaces of Multilingualism. Language & Communication. 25. 197-216.

Mooney, A., & Evans, B. (2015). Language, society and power. New York: Routledge.

Parzer, Michael, Astleithner, Franz, and Rieder Irene (2016). Deliciously Exotic? Immigrant Grocery Shops and Their Non-Migrant Clientele. International Review of Social Research, 6(1). 26-34.

Sabaté i Dalmau, Maria (2013). Fighting Exclusion from the Margins: Locutorios as Sites of Social Agency and Resistance for Migrants. In A. Duchêne, M. G. Moyer, C. Roberts. (Eds.), Language, Migration and Inequality: A Critical Sociolinguistic Perspective on Institutions and Work. Multilingual Matters. 248-271.

Tavares, Bernardino (2018). Cape Verdean migration trajectories into Luxembourg: A multisited sociolinguistic investigation.Unpublished PhD thesis: Université de Luxembourg

Appendix

[1] https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/cartes-thematiques.html, last consulted on 03.07.2018