Ethnic Businesses in the Neighbourhoods of Tunnel and La Borde

Saara Jones and Susan Effamonh

Abstract

This study tries to understand the purpose of the different signs found on ethnic businesses’ window displays. The paper focuses on the neighbourhood of Tunnel and Borde which have a high percentage of the migrant population and show visible signs of multilingualism. We collected the data by taking pictures of the different grocery shops and by analysing the way in which different languages are being used and the possible intended audience and purpose of the signs. We found that while most signs are written in French or Lingua Franca English, some signs were only for a specific community in a non-official language, therefore intended to a specific migrant community.

- Introduction

Prior to this research, we had noticed that in the neighbourhood of Tunnel and Borde in Lausanne, there was a diverse soundscape. We could hear different languages being spoken around, so this is why we chose to investigate further and see if there would be visual proofs of what we could hear, and we were not disappointed. We found plenty of ethnic businesses which displayed different degrees of multilingualism and a variety of languages. This paper will try to understand what the purpose of the signs of ethnic businesses’ window displays is, which languages are being used, why and to whom they are addressed. In previous research, Sabaté i Dalmau shows the importance of ethnic businesses in translating ads into migrant languages to advertise and give the opportunity to different migrant communities to access and understand offers that were at first only in Spanish (2013). Also, when studying the linguistic landscape, we will look into “uncovering the everyday communicative strategies of the people who actually use a particular space” (Mooney and Evans 2015:96). This paper will start by explaining more in detail previous research done on similar matter. Then, it will show why we chose the specific neighbourhoods, where they are located and statistical information about them. We will explain which method we used, how we collected our data and why we selected it. Finally, we will discuss our results and conclude with possible further studies.

- Theoretical framework

Linguistic Landscape, like Mooney and Evans explain, is “a testament to the languages actually being used in a place” (2015: 97) It is a visual proof of an invisible soundscape. They suggest that “some research (…) can provide insight into linguistic diversity not captures by official top down discourses or even by official audits (e.g. a census).” (2015: 97) This is what we will be looking at when analysing our photos. Signs can be top-down which usually means official government-made messages or bottom-up which are made by individuals or smaller groups (Mooney and Evans 2015: 87). Unlike Mooney and Evans who would consider signs produced by business owners as top-down, we think of them as bottom-up because of the smaller scale of ethnic businesses.

Also, Sabaté i Dalmau’s research aimed to study on how the Locutorios fill up the linguistic gap with their services to the undocumented migrants, because the ICT multinational companies in Catalonia and Spain do not deem it economically profitable to invest in their migrant languages. According to the official statistics and references in her article, Catalan as an autonomous community, on the north-eastern side of Spain has witnessed a great influx of migrants, notably from Europe, Africa and South America. Evidently, these migrants came along with their linguistic repertoires but unfortunately, the ICT multinational companies in Catalonia (Spain) do not want to incorporate these newly arrived languages into their linguistic advertising approach to customers because they think that they won’t make a significant profit from the languages of these migrants. So, the Locutorios business, which are ethnic businesses owned by migrants who are well established in Catalonia, offer not only access to the internet, computers, cabin calls, prepaid phone cards, top ups, photocopying, fax and money transfers, to these other (undocumented) migrants but these locutorios also provide the platform on which these undocumented migrants can communicate with the outside world, in a language in their repertoires. Through their workers, the locutorios also offer crucial services of: translation of text messages and promotion offers from Spanish into migrant languages like Urdu, and filling of administrative.

However, because it has not been previously done, our research focus will be on ethnic businesses and their linguistic landscapes, in Tunnel and La Borde neighbourhood, Lausanne in Switzerland. For the purpose of this study, we will refer to other languages that are not French language as non-official languages, French as the official language because it the local authorised language, spoken in this region of Switzerland and English language as the lingua franca because it is the “global language” (Pennycook 2003:516).

- Contextualisation

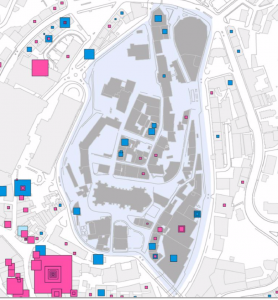

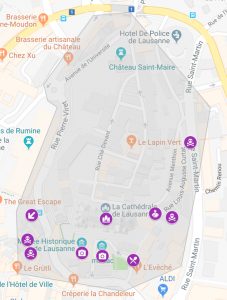

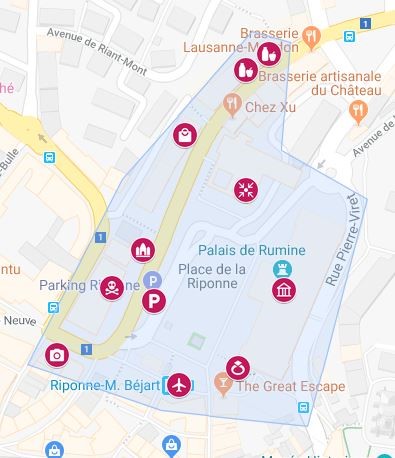

Figure 1. Shop locations on Google maps

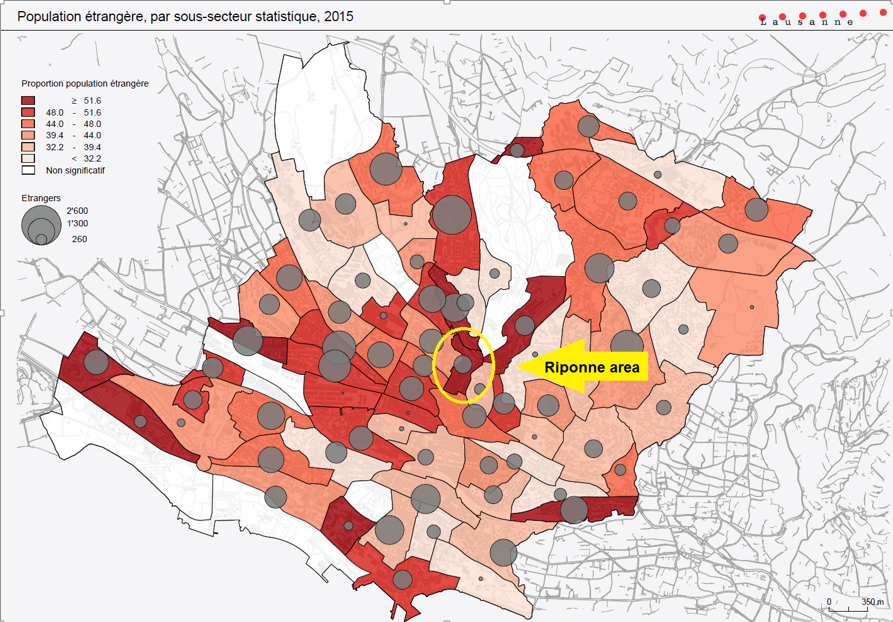

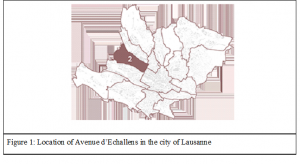

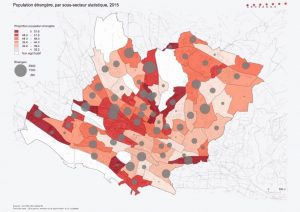

Figure 2. Percentage of foreigners in Lausanne

This paper focuses on the two main streets of the neighbourhoods of Tunnel and La Borde in Lausanne which were chosen because of previous soundscaping in the area. They are situated relatively close to the center of the city and Tunnel is part of the center district and La Borde of Borde/Bellevaux, but both situated next to each other. When we first went with the intention of taking pictures and collecting data, we were looking for any signs of multilingualism, but we discovered that they were mostly on the window display of ethnic shops. Therefore, we decided to focus on ethnic businesses. In Figure 1, the green dots represent the different shops we found although there were many more, but we decided to filter through the multitude of shops to a selection that best represent the multilingualism of the area. According to the official statistics of Lausanne, more than half of the inhabitants of these two areas are foreigners (2017). We can see in figure 2, the blue dots show where our two neighbourhoods are located and where we collected our data. They are both in dark red because more of half the inhabitants are immigrants which explains why we have found so many ethnic businesses around there. Tunnel/Riponne has 60,6% of foreigners and La Borde 59,8%. We could not find more details on the origins of the foreigners of the neighbourhoods, but in the whole of Lausanne out of all the foreigners, there is a majority of European migrants (65,3% – Germans, Italians, French, …) but also a smaller but considerable proportion from Asia (7,7% – China, Sri Lanka, …), from South America (5,2% – Brazil, Chili, Ecuador, …) and from Turkey (1,5%). The neighbourhoods are quite vibrant with many restaurants, hairdressers, cafés and specialised shops, but according to the official statistics of Lausanne, the number of businesses in the area (and Lausanne in general) has decreased since 1995 and some of the shops we photographed seemed to have already closed down when we took photos of them.

- Methodology

The data for our study was collected on the 5th of November 2018, based on previous soundscaping. We started in the neighbourhood of Tunnel but continued up to the main street of La Borde. We took multiple photos of different ethnic shop window displays and signs because there were many businesses on the two main streets and most of them displayed non-official migrant languages. Therefore, since almost all our pictures were of shops, we decided to focus on ethnic businesses.

We selected ten photos of businesses for this study: ‘Akdeniz Voyages’ (travel agency), ‘The next cut’ (barber shop), ‘Au Bornéo’ (café), ‘Nice people’ (shop), ‘La Tienda de la Esquina’ (shop), ‘Thai délices’ (restaurant), ‘Créacion Del Tata’ (restaurant), ‘Chez Bui’ (shop), ‘Sam’s piercing and Tattoo’ (tattoo shop). All of them used language in a different way to advertise to locals or diverse migrant communities like the Spanish and Asian communities. Later, more data were collected from oral interviews that we conducted with the owners of ‘Chez Bui’, ‘Akdeniz Voyages’ and ‘Thai délices’ and we got oral permission from them to use our discussion with them in our data analysis.

Tunnel and La Borde neighbourhood have delivered our expectations of finding non-official languages there because of the dominant presence of ethnic businesses in it. Our research has proved that the soundscape is also visible in the linguistic landscape. It is rather an interesting project and we have learnt not to just walk into any shop without observing and mentally analysing the language signs that we find there.

5. Results

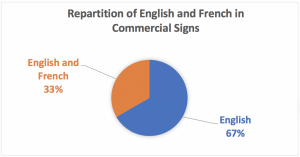

Fig. 3. Language distribution in signs

For this study, we had to choose ten pictures to focus on. Because there were too many different languages and language combinations, we divided them into three categories depending on the main language used: non-official, official & non-official and lingua franca. Three signs were fully written in non-official languages, three signs were in non-official languages but also in French and finally, four signs in Lingua Franca (English).

Image 1. Turkish travel agency

Image 2. Turkish ad

Image 1 is a picture we took on the window display of a Turkish traveling agency and the languages we found in it are in French, Turkish and English. It is a bottom-up advert and French language has a dominant presence because it is written in big font. According to the owner of the office, its targeted customers are French speaking travellers. However, there is a concert advert that is completely written in Turkish language (Image 2). This signifies that the physical space of the agency office is a medium of making relevant the Turkish language for Turkish people, in a French speaking neighbourhood. English language does not play a significant role in Image 1 because it is written in small font but is necessary because “it is the language of international communication in the vast majority of advertisement”(Piller 2001:164).

Image 3. Chinese and Thai ads

Image 3. Chinese and Thai ads

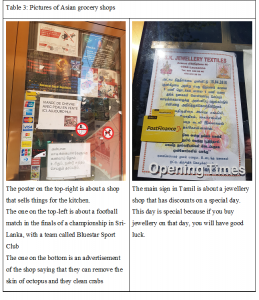

The presence of Asian languages is obvious in Image 3, and notably are Chinese and Thai languages. In the interview we had with the shop owner, his shop provides unique Asian products for the Asian communities living in this neighbourhood. On the window display, the price list and Thai massage advert, written in French is for locals who like Asian products. This shop also serves as adverts space for Chinese Buddhist religion, and a job proposal of 80%-100%. These adverts are written in Chinese and Thai, respectively and they are also bottom-up adverts. Image 3 is also a good example of non-official languages being used to target a specific language group.

Image 4. Tattoo and piercing ad

Image 4. Tattoo and piercing ad

Image 4 is a typical example of English language as a global language, staking its presence in Tunnel and La Borde neighbourhoods, in Lausanne. As seen on the window display of this shop, every word is written in English and mostly in big font, too. The use of English language indicates that its targeted customers are only English speakers. The featuring of the crown symbol which is popularly associated with the Queen of England, might be an indication that the owner of the shop is from the United Kingdom and therefore is staking a place for English language in a French-locally spoken neighbourhood.

Image 5. Ads on a Spanish shop

Image 5. Ads on a Spanish shop

Based on the linguistic signs in Image 5, we could say that it is a Latino shop. This means that even as ‘Bienvenue’ is written boldly in French language,and ‘Open and Pull’ in English Language, the dominant language on the window display is Spanish language. As advertised in Spanish language, this shop sells food items (“productos latinos”) and Lebara top-up cards. It also buys euros and dollars, as well as provides fixing up services of perhaps broken car windows. Thus, it is a shop that provides information for different kinds of services. It targets the Latino community but is obviously open to locals through the welcome signs of (‘Bienvenue’, ‘Open and Pull’) written in French and English.

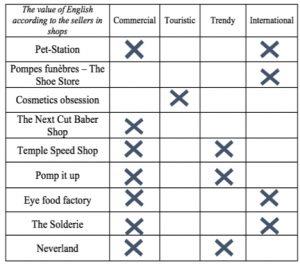

- Discussion

Our results reveal the diversity of purposes and addressees. Most shops, of course, had signs in French or English to open the business to a majority of customers, but we noticed that some shops specifically intend some ads or messages for a specific community. A few signs were only written in a non-official language therefore solely focused on one immigrant language speaker group. They represent visible signs of migration as also revealed in the statistics that show the two neighbourhoods have some of the highest proportion of migrants in Lausanne. We could not study and interview the owners as much as Sabaté i Dalmau did, but we were able to find out that ‘Chez Bui’, for example, targets specific ads to the Chinese community or adverts jobs directly for Thai speakers. In his study, Blommaert describes the LL of Antwerp as mostly Turkish and Belgian being visible and audible but also found traces of Chinese migration through a sign written in Chinese advertising a flat to rent (2013: 45-46), which is also what we were able to find in Lausanne. The poster ad fully written in Turkish directly addresses the Turkish community, but we found out that the owner only speaks in French to his customers.

- Conclusion

This study set out to understand the purposes and targeted audiences of the different signs found on window displays of ethnic businesses, in Tunnel and La Borde neighbourhoods, in Lausanne. Our findings confirm with the findings in Sabate i Dalmau (2013), namely that ethnic business provide various non-official languages services like: selling of top-ups phone cards, money transfers, and advert services. It would have been interesting to study linguistic services (e.g. to fill in administrative forms in French as the official and locally spoken language) provided to migrants in these neighbourhoods; however, this was not possible in the scope of this study but further research could be undertaken on it.

References

Blommaert, Jan. 2013. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes: Chronicles of Complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. pp. 45-6.

Mooney, A., B. Evans. 2015. Linguistic landscapes. In A. Mooney and B. Evans (eds.),Language, Society and Power: an Introduction. London: Routledge, pp. 86-107.

Pennycook, Alastair. 2003. Global Englishes, Rip Slyme, and performativity, Journal of Sociolinguistics 7/4, p. 516.

Piller, Ingrid. 2001. Identity constructions in multilingualism advertising, Language in Society 30, p. 164.

Sabaté i Dalmau, Maria. 2013. Fighting Exclusion from the Margins: Locutorios as Sites of Social Agency and Resistance for Migrants. Bristol: Mulilingual Matters.

Websites

Official statistics from the website of Lausanne. Available on https://www.lausanne.ch/en/officiel/statistique/quartiers/cartes-thematiques.html Accessed on the 04.12.18.

Appendix

Image 1.1 Nice People Shop

Image 1.2 The Next Cut Barber Shop

Image1.3 Thai Délices Restaurant

Image 1.4 Créacion Del Tata Restaurant

Image 1.5 Au Bornéo bar à café

Image 1. 6 Rapid Lunch Pastelaria