ABSTRACT

This study examines the use of language at the main station of Lausanne in order to see if it coincides with the city’s international status. The analysis of multiple signs demonstrated that the main station essentially uses its national language, French, which is directed to its population but also uses it to presents itself.

- INTRODUCTION

The significant presence of bilingualism and multilingualism promoted in more and more societies influences the way language is represented in public places. This is the particular subject of Linguistic Landscape (LL), that attempts to analyze how language is represented in public places, through the way it is used in written signs. More precisely, it seeks to study what and how language(s) is(are) represented, in order to learn more about what message it sends, and how it informs us about the language use in a certain place. In this study, I will examine the city of Lausanne, in Switzerland, referred as the ‘‘Olympic City’’. I will specifically focus on the railway station of the city, and demonstrate how it partially embodies its international reputation, through the prominent use of its national language, French, in infrastructural and commercial signs. Overall, linguistic studies about Switzerland discuss the issue of the country’s multilingualism, and how it is dealt in the Swiss Confederation as well as among the local population. Instead, my main focus will be on how the use as well as the presentation of language(s) in the main station of Lausanne do or do not represent the city’s Olympic status. Following this introduction, I will, first, introduce the main notions about LL, then a contextualization of the city of Lausanne as well as the railway station as well as the city of Lausanne, and finally, I will proceed to my data and its analysis.

- THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

According to Annabelle Mooney and Betsy Evans (2015), many sorts of linguistic and semiotic material are found in public places, enabling people to situate themselves. They are various, and are not necessarily noticed, since many people know their surroundings, and, thus, do not require them. They constitute the studies of Linguistics Landscapes (LL) and Semiotic Landscapes (SL), that observe how language and objects/materials contribute to the ‘‘construction of space’’ (Mooney and Evans, 2015: 87). Jennifer Leeman and Gabriella Modan (Leeman and Modan, 2009) argue that LL studies, first, focused on taking into account every representation of languages and comparing their numbers between each of them in relation to the landscape in which they were situated, without considering the meaning of it. The different types of LL essentially depend on which language is represented, who produced them, and who is targeted. On the one hand, we find officials signs, generally produced by the government for instance, and non-official signs. On the other hand, we find bottom-up signs, which are produced by people, and can be identified from the message they convey and the materiality of the sign, and top-down signs, typically from the government. For instance, we immediately recognize the significance of a message if it is produced on a hard material, rather than if it is poorly written on a piece of paper. However, it is not always easy to identify either of these two. In that case, we can identify signs on individual shops as bottom up, since they chose personally choose the display of their shops.The materiality of the sign can help too, as stated previously. There are different kinds of signs (Mooney and Evans, 2015: 92): regulatory discourses (traffic signs, indicating official/legal prohibitions), infrastructural discourses (‘‘directed to those maintaining the infrastructure or to label things for the public’’), commercial discourses (ads), and transgressive discourses (‘‘any sign in the ‘wrong space’’’, generally graffiti, which gives marginalized people a voice).

In addition to the way language is represented, the message of a sign can also depend on its position. Geosemiotics, specifically, emphasizes the importance to take into account not only language, that plays a part in the understanding in linguistic signs, but all the semiotic signs, such as the placement of the material or the colors. Indeed, the placement of a sign tells us about ‘‘its meaning and the intentions of the sign maker’’, that is to say it needs to be well-placed, or else the population targeted will probably not understand, making us question the agency of people. According to Mautner, ‘‘physical signs can function as ‘boundary markers’ … playing an important part in carving up space into public and private areas, and into zones where it is permissible to enact some social roles (e.g., cyclist or angler), but not others (e.g., busker or dog-walker)’’ (Mooney and Evans, 2015: 91). Overall, multilingualism in LL can tell us a lot about the official language of a place, in relation to the actual use of the population, which does not necessarily represent the official language of the place.

There does not exist a lot of linguistic work that deals with linguistic landscape about railways station, especially in Switzerland. The work of Wareesiri Singhasiri (Singhasiri, 2013), is the most relevant article for the purposes of this project. It focuses on the Thai context, and demonstrate the influence of internalisation/globalisation through LL in the railway station of Thailand. Specifically, the author attempted to observe the rising use of English in infrastructural and commercial signs, because of the place’s visitors, mostly communicating in English. They differentiated their data collection by LL items created by the State Railway of Thailand, and by the companies and local shops. They also delimited language in terms of monolingual and bilingual. In the first category, Thai was mostly used in infrastructural signs, and the use of English was only found in warning signs, to be careful of hustlers who would mislead tourists in their destination / where they ought to go. Therefore, the State Railway seems to be conscious of the use of languages, by addressing specifically local people and visitors. Moreover, the companies, because their target was only visitors, used English, whereas local shops (food, books) used Thai and English, since their target was everyone. Overall, they observed that more and more signs were bilingual, both in Thai and in English. The fact that local shops used English too suggests that they are aware of the significance of that language, and the status/power it gives them access to.

Jennifer Leeman and Gabriella Modan’s study (Leeman and Modan, 2009), is also a great example of a more complete qualitative LL analysis. In their work, they attempted to demonstrate how Chinatown, in Washington DC, changed from a neighborhood shaping the identity of Chinese people, to a ‘marketing commodity’ (Leeman and Modan, 2009: 333). To do so, they did a historical contextualization, discovering that the settlement of the neighborhood proceeded in a few phases, during which LL changed accordingly. Therefore, their method concentrated on a micro-level, that is a subjective representation according to them, something that is constructed according to what is displayed in the public sphere, and with the languages used. The study of historical contextualization and the analysis of LL enabled them to demonstrate the evolution of Chinatown that shaped the neighborhood to what it is today. Particularly, the settlement of the city to add more Chinese symbols, as well as the rising of more and more large-scale commerce reversed the place to an ‘exotic’ neighborhood, especially for non-Chinese speaking people. In other words, the aim of the rising use of Chinese was not to favor the use of a language, or to give a minority access to information to a community, but it was used as an aesthetic element favoring economic profits. That is how LL can help us understand unfolding social processes.

- CONTEXTUALISATION

The city of Lausanne is the fourth largest city of Switzerland, situated in the French-speaking part, with more than 140,000 people domiciled or that have permanently stayed there. It is generally described as the ‘‘Olympic city’’, implying an international aspect, and is very touristic. It finds itself in a particular place linguistically speaking. Generally speaking, Switzerland was formed by multiple heterogeneous groups that wanted to merge together as a homogenous nation (Mayer, 1951: 157). Despite the ‘cultural heterogeneity’ of Switzerland, Kurt Mayer states that a national equilibrium is settled in order to avoid tensions within the country (Mayer, 1951: 157). Switzerland’s national languages are German, French, Italian and Romansch. They have been represented equally as the national languages in the Confederation politically, since the creation of the Swiss Constitution in 1848 (Schwab, 2014: 3). The federal laws are published in the three official languages they are all equally authoritative, but most of the official documents are only written in German and French. Indeed, according to Swiss statistics, German is spoken by 62.8% of the population, French by 22.9% of the population, Italian by 8.2%, and Romansch by 0.5%. Moreover, although the three official languages are equally acknowledged by the Federal Constitution, they are unequal in terms of importance.

Image 1 – Distribution / proportion of national languages in Switzerland: the yellow part represents the German speaking proportion, the blue part represents the French speaking proportion, the green part represents the Italian speaking proportion, and the red part represents the Romansch proportion.

Image 1 – Distribution / proportion of national languages in Switzerland: the yellow part represents the German speaking proportion, the blue part represents the French speaking proportion, the green part represents the Italian speaking proportion, and the red part represents the Romansch proportion.

Their linguistic boundaries are clearly defined by territorial areas; however they are not so clear between French (Western part) and German speaking zones (Central and Eastern part), and the Italian speaking zone (Southern part) is separated from the rest of the country because of the Alps. Overall, the number of German-speaking people is more significant than French-, Italian-, and Romansch-speaking people. This linguistic pattern through the population has been quite constant, similar since the 17th century (1800), when data started to be collected. Mayer also noted that the second generation of Swiss used the official language in which reside, instead of speaking their parents’ language. Moreover, Switzerland inhabitants has an average of 2.0 languages spoken, representing the third multilingual European country (Schwab, 2011: 8). Overall, this demographic equilibrium is maintained by the political measures settled by the Confederation, to avoid conflicts. Significantly, the official languages are all used in the official documents, and the proportion of the representatives working for the Confederation has to be equal to the three most important national languages (German, French, and Italian) (Kobelt, 2011: 54). The research of Georges Lüdi, Katharine Höchle and Patchareerat Yanaprasaart (Lüdi et al., 2010), attempted to see the use of language(s) and cross-speeches in a professional environment in Basel, a bilingual city of Switzerland. They observed that English is the most used language after German in Basel, just like it is the case in a lot of cities of the world, however, the linguistic landscape is not representative of a population’s language distribution. Generally, the national language is still used because it plays an important role in identity. According to them, the history of Switzerland’s languages favored the construction of ‘‘a culture of communication’’ (Lüdi et al., 2010: 77) that made acceptable the plurilingualism of the country (education that favored the learning of a second national language).

Lausanne is situated in the Romandie, the French part of Switzerland. Lausanne became the Olympic Capital, the headquarters of the International Olympic Committee since 1915, and was named the Olympic Capital in 1993. It therefore has an administrative role in that domain, heading many international federations. It became economically strong after the economic crisis of the 1990s, currently having many research institutions settled there, like the Federal Institute of Technology, and the University of Lausanne.

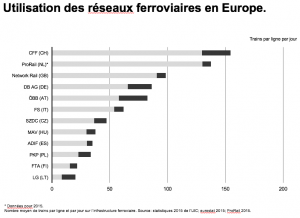

Generally speaking, Switzerland is the country of Europe that uses the most its railways, counting a complex network, as seen in the Image 2 (Swiss railways statistics). Significantly, the Image 2 demonstrates the number of trains used in many European countries’ trains system.

Image 2 – Use of the railway networks in Europe according to the official main station of Switzerland’s statistics.

Image 2 – Use of the railway networks in Europe according to the official main station of Switzerland’s statistics.

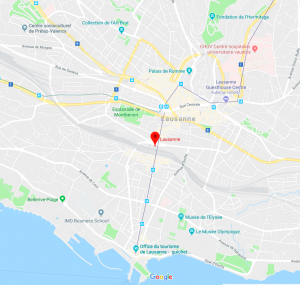

Image 2 – The location of the main station of Lausanne in the city.

Image 2 – The location of the main station of Lausanne in the city.

Moreover, as seen in Image 3, the main station of Lausanne is situated between the lake, and the center of the city, that are highly visited / busy places. The particularity of the main railway station of Lausanne is that, in addition to connecting Lausanne to other cities of Switzerland, it connects Switzerland, more globally, with direct trains to other towns in Europe, such as Milano and Venezia in Italy, and Paris in France. According to the main station’s statistics, there are around 110,000 passengers every day. The main station of Lausanne is quite frequented, mostly by Swiss passengers.

- METHODOLOGY

As this study is part of a collective project of the University of Lausanne, each student of the course ‘‘Introduction to Multilingualism’’ was required to take pictures involving material representing language(s) from what they wanted to examine, and upload them on Google Map Drive. This project was inspired by a Spanish project, ‘‘Lenguas pa’ la Citi’’, demonstrating in what way Madrid can be considered as a multilingual city. During this project, I initially had trouble finding a clear subject, causing my data collection to be insufficient. As I narrowed my subject to the national representation of the main station of Lausanne, more data was collected specifically on infrastructural and commercial signs. Also, because it is a place that is familiar to me, and which is very crowded most of the time, it was difficult to observe all the signs that are present. I decided to collect data at night, so that I was able to take time, and observe the totality of the place. The data collection counted around thirty pictures, in which I could immediately see the importance of French, the national languages of Switzerland, and of English. Since I concentrate on the type of signs that are infrastructural and commercial, following Singhasiri (2013), I decided to follow a similar structure, that is to use monolingual / bilingualism (multilingualism in my case) categories, and infrastructural as well as commercial categories. Overall, my data collection was essentially top-down and official signs.

- RESULTS

Figure 1 – Front of the main station of Lausanne.

Figure 1 – Front of the main station of Lausanne.

Figure 2 – Left front of the main station of Lausanne, next to the ‘Lausanne Capitale Olympique’ sign.

Figure 2 – Left front of the main station of Lausanne, next to the ‘Lausanne Capitale Olympique’ sign.

Figure 3 – Custom service situated in the halls of the main station.

Figure 3 – Custom service situated in the halls of the main station.

Figure 4 – Tickets machine of the main station.

Figure 4 – Tickets machine of the main station.

Figure 5 – Infrastructural signs, indicating the opposite directions of the city and the lake.

Figure 5 – Infrastructural signs, indicating the opposite directions of the city and the lake.

Figure 6 – Infrastructural sign indicating the destinations of the time in Germany and French.

Figure 6 – Infrastructural sign indicating the destinations of the time in Germany and French.

Figure 7 – Shop situated at the front entrance of the main station

Figure 7 – Shop situated at the front entrance of the main station

Figure 8 – Advertisement sign situated at the front entrance of the main station.

Figure 8 – Advertisement sign situated at the front entrance of the main station.

A) Quantitative analysis:

Figures 1 to 6 represent the first category of infrastructural signs, and all fall in the type top-down, since they are official signs from the Swiss railways, except for the shop sign in Figure 7, and for the advertisement in Figure 8, since they are commercial signs. Figures 1 and 2 represent the front of the main station of Lausanne. Only French is used in the first figure, describing its Olympic status. The second one shows the official sign of the Swiss railways, ‘‘SBB CFF FFS’’, in German, French, and Italian, the three of the national languages of the country in order of significance. They found themselves on each side of the Olympic title. Figure 3 is the official customs of the Swiss Confederation, in which written declarations are found, destined to tourists of Europe. We notice that the three national languages are represented, in the same order of significance as in Figure 1. However, Figure 3 is the only exception, changing the order of German-French-Italian we tend to have, in other figures; indeed, the order of that sign is the same except for the title of the sign, which begins with French and then follows with German, Italian and English. There is the presence of English too, following the three languages, in the titles, and explanations. It is interesting to note that the title of the Swiss Confederation, at the left top of the sign, represents the three national languages as well as Romansch. Moreover, the indication of what the sign is, is presented in French, largely at the bottom. Moreover, it is situated at the side of the hallway, not always visible when there is a lot of passengers. Figure 4 is the official train ticket of the main station, as the sign of the Swiss railways ‘‘SBB CFF FFS’’ are presented. The indication of its purpose is presented with the word ‘‘ticket’’, at the side of the machine, and is translated in the three significant languages, as well as English. There is also a publicity at the side, from the railway station, and a map of the Vaud canton, both written in French. Figure 5 and 6 demonstrate transportation indications. In figure 5, English is used to show where to find the city, while French designates the lake’s location. In figure 5, French and German are used to represent cities from the French or the German part of Switzerland. Overall, French is the language the most represented, followed by indications in the national languages of German and Italian, and finally English.

The category of commercial signs, portrayed by Figures 7 and 8, are top-down as well. The difference between both of them is that French is predominant in the display, in Figure 7, whereas English only is used in Figure 8. An English map of the hotel’s location is also provided at the bottom of the sign. Contrary to infrastructural signs, languages do not seem to be mixed together.

B) Qualitative analysis:

We remark that there is a predominance of the national language, suggesting a national system of the Swiss railways. First, Figure 1 demonstrates the way Lausanne wants to be presented to people, especially foreigners: the identity is concentrated in its Olympic status, implying an international reputation. However, it is not conveyed in English but in French, implying that Lausanne’s identity is linked to its national language, therefore using French symbolically. It is also emphasized by the fact that the official signs of Switzerland railways are positioned at the side of the Olympic title, suggesting its secondary place in Lausanne’s identity. Yet, the three most significant Swiss languages were represented in the customs’ declarations, and the ticket machine, facilitating accessibility to all Swiss people, but prioritizing French speaking people (Figures 3 and 4). English was also used, directly addressing foreign people, as it is the case at figure 8, which is also situated at the main entrance of the station. However, destinations were not indicated in English, but according to the location of a particular place. Indeed, places that were situated in the German part of Switzerland, or in parts that are bilingual, are represented in the specific language, in two languages in the latter case. Significantly, in Figure 6, we notice Murten/Morat, and Fribourg/Freiburg. The order of the language chosen in these two bilingual cities demonstrate the significance of the most used language, German in the first one, and French in the second one. It is, therefore, addressed to Swiss people of these places, but also translated in order to be understood to other speaking Swiss people.

- DISCUSSION

Overall, my results demonstrate a clear link between the use of national language, and the construction of Lausanne’s identity. Indeed, by presenting itself as the Olympic Capital in French, it contradicts it international title, and claims its national identity first. This follows Jennifer Leeman and Gabriella Modan’s reasoning, in the sense that French is used symbolically to strengthen Lausanne’s identity within the Francophone part of Switzerland (Romandie). The same pattern could be seen with cities situated in the German part of Switzerland. We could imagine a comparable analysis to railway stations of these cities. Similar to Singhasiri’s work, the use of different languages indicates that the Swiss railway station of Lausanne is aware that the railway networks is mostly composed of Swiss passengers. Besides, the use of English is directly addressed to European foreigners, enabled by the direct access connections to European cities from the main station. Although Lausanne is quite a touristic place, there is note a lot of English use. When it is the case, they are clearly addressed to visitors, in customs services and hotel ads. However, the signs indicating the directions to the lake and to the city seems to be directed to foreigners.

Finally, the fact that the collection data is essentially composed of top-down as well as official signs, inform us about the languages policies of the main station, and more globally of Lausanne. Overall, the main station of Lausanne uses languages according to whom it convey information: French is essentially used in order to inform its population; the other national languages (German and Italian) are also used when directing to the more global population of Switzerland; and finally, English is only used towards foreigners, through advertisements or custom policies.

- CONCLUSION

This linguistic project, concentrated on the main station of Lausanne, allowed me to contradict the city’s international status. Instead, I could demonstrate, through its systematic use of French, that the main station of Lausanne follows a national and cantonal policy, which could be the case in the rest of Switzerland. What is more, that clearer knowledge on Lausanne’s language policy, informs us about the construction of the place, strongly linked to its national and Romande identity. Overall, the main station of Lausanne is a place for its national passengers, of all Switzerland, and slightly takes into account its touristic significance. As it is a small university project, I could not study the entirety of the Lausanne’s station. A brief historical contextualization could have been provided, as it could have been interesting to study its evolution, especially since it is currently being rebuilt, drastically modernizing it.

REFERENCES

Kobelt, Emilienne. ‘‘Enjeux de la promotion du plurilinguisme dans les administrations publiques : le cas de l’administration fédérale Suisse’’ Plurilinguisme et monde du travail : Professions, opérateurs et acteurs de la diversité linguistique (2001)

Leeman, Jennifer, Modan, Gabriella. ‘‘Commodified language in Chinatown: A contextualised approach to linguistic landscape’’ Journal of Sociolinguistics 13/3 (2009): 332–362.

Lüdi, Georges, Höchle, Katharina, and Yanaprasaart, Patchareerat. ‘‘Patterns of language in polyglossic urban areas and multilingual regions and institutions: a Swiss case study’’ 39 (2010): 55-78.

Mayer, Kurt. ‘‘Cultural Pluralism and Linguistic Equilibrium in Switzerland’’ American Sociological Review 16/2 (1951): 157-163.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2087688 (last consulted 01.06.2018)

Mooney, Annabelle, Evans, Betsy. ‘‘Chapter 5: Linguistic Landscapes’’ Language, Society and Power. Routledge (2015): 86-107.

Schwab, Philippe. ‘‘The Swiss Parliament as a Plurilingual forum’’ Union Interparlementaire (2014)

Singhasiri, Wareesiri. ‘‘Linguistic Landscape in the State Railway Station of Thailand: The Analysis of the Use of Language’’ The European Conference on Language Learning (2013)

Web:

http://ddc.arte.tv/uploads/program_slideshow/image/caption/2142802.jpg (last consulted 01.06.2018)

http://www.lausanne.ch/en/lausanne-en-bref/lausanne-un-portrait.html (last consulted 01.06.2018)

https://www.sbb.ch/fr/gare-services.html (last consulted 01.06.2018)

https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/population/langues-religions/langues.assetdetail.4542469.html (last consulted 01.06.2018)

http://ddc.arte.tv/uploads/program_slideshow/image/caption/2142802.jpg (last consulted 10.06.2018)