Arlinda Ramqaj & Sophie Künzi

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to focus on the use of English as a lingua franca in Flon (Lausanne, Switzerland) in order to highlight the values and purposes given to the English language. Through the observation of commercial signs present on window displays and semi-directed interviews with sellers, we analyse how English and French interplay. Our hypothesis is that sellers decided to settle their establishment in Flon because it is a commercial and cultural centre. Thus, it justifies the use of English in the shop names. English therefore would have a commercial value. Another hypothesis is that the English brand names were associated to sellers that speak this language. After the analysis of our data, our hypotheses were disproved. Most of the sellers do not speak English or just enough to be understood. The value given to English is commercial but the aim of their English logo is not to attract foreign customers. This “paradox” can be partly explained through the fact that French translation of the concepts of the store are not possible.

1.Introduction

Lausanne is one of the most diverse cities in Romandie. Since it acquired the label of Olympic city, it has become an important cultural centre. Composed by different neighbourhoods, we decided to focus on the neighbourhood of Flon: one of the most well-known neighbourhoods in the heart of the city. One of the many languages used in this region is English, which is no surprise since it is a global language or more commonly designated by lingua franca (Kaur 2013; 214). The aim of this paper is to focus on the use of English as a lingua franca in this neighbourhood through observation of window displays and brand logos, in order to highlight the values and purposes given to the English language. This research project aims to see the connection between the use of English on branding or logos and the owners of those shops. This study would fill in the lack of research done in this region. Data collection in this study consists of taking pictures of different English commercial signs throughout the Flon and interviewing the owners or employees of those shops or restaurants. From a sociolinguistic point of view, we analysed our data with a mixed quantitative and qualitative approach which enables us to highlight in detail the interconnexion between English and Flon. This study will introduce a theoretical framework in section 2 based on the examination of other works that studied commercial signage, linguistic diversity in a neighbourhood and English as a global language. In sections 3 and 4, we will provide information about the area chosen and the methodology that we used. In the last sections, 5 and 6, we will provide the results, their analysis and their discussion. Section 7 will conclude our study.

2. Theoretical framework

According to Mooney and Evans, the world is surrounded by “semiotic material”. Linguistic landscapes are defined as “the attention to the use of languages and other meaningful objects in the construction of space” (Mooney and Evans 2015: 87). These signs are useful in order to understand the social construction of space in which multilingualism occurs. Moreover, the researchers assert that there are two different types of signs, top-down and bottom up (89). Those signs need a thorough examination when considering their emplacement (90). “Considering multilingualism in LL can also tell us about the languages used by inhabitants of those spaces and whether this “matches up” with the official languages” (97). This paper helped us define our subject, it oriented us towards the analysis of commercial signs and it also sets our first hypothesis that the commercial situation of Flon plays a role in the use of English in this region. English is therefore considered as a global language.

Many attributes were given to English. According to Piller, English has been established as a language of authority, he explains that “everyone wants to be perceived as a global player, and such perception is best achieved by using English” (Piller 2001: 161). The question of English as a global language is explored by Crystal, who states that “language achieves genuinely global status when it develops a special role that is recognized in every country” (Crystal 2003: 3). Furthermore, the extension of English as a lingua franca helps solve problems of communication within people of different backgrounds (Lüdi 2001: 57). For Görgülü, English is explored as being a strategic tool in order to attract people and also for its “trendiness”. For us, these aspects of English set the beginning of our understanding of its complex role. Therefore, we wanted to explore the use of English in the light of these elements and especially the use of English as a global language. We also consider a term used by Görgülü in her study, which is the “Englishization” of signs (Görgülü 2018: 139).

In Lausanne’s context, there is a lack of research in the field of commercial signage. Additionally, only a few studies examine the use of languages in Switzerland’s commercial signage. One of them investigates the use of multilingualism in hair salon names, especially focusing on the use of the official national languages and a fifth language, English (Paviour-Smith 2016: 231). English is in this study considered as a global language or more commonly designated by lingua franca. “English as a lingua franca is nothing more than a useful tool: it is a “language for communication”. And because of the variety of functional uses of global English, English has also a great potential for promoting international understanding.” (House 2001). This viewpoint is shared throughout Switzerland. Swiss people use English as a way to understanding each other at the expense of national languages.

An additional hypothesis was formulated on the basis of those studies. Since no studies on multilingualism have been done in Lausanne yet, it opened our research field. Given the use of English as a lingua franca across the globe and in different countries or cities, we suggest that English is also used as a global language in Switzerland and especially in Lausanne. In Switzerland, multilingualism is defined by the territoriality principle, the four national languages are defined by geographical and political boundaries (Stotz 2006: 249). Nonetheless, the territoriality principle is not as concise and delimited as it is supposed to be. Indeed, languages in Switzerland overlap even if in some places the dominance of one specific language is possible. What interests us in the context of this study is the presence of English as an almost “fifth language of the country” (Stotz 2006: 249).

3. Contextualization

Before 1950, Flon was an industrial region, constituted by warehouses. Afterwards, Flon is linked to the city of Lausanne and becomes an “original, creative and alternative neighbourhood” (Brève histoire du Flon, n.d.).Situated in the centre of Lausanne, the Flon is a neighbourhood of 55’000 m2,mostly pedestrian. It is served by public transportation such as buses and the metro, which allows it to be a very accessible district. What was historically an industrial place is today a centre of activities and a place of interactions. The 28 bars and restaurants in addition to the 61 shops, attract over 7.5 million people per year (A district to experiment, n.d.). The use of English on window displays and brands’ logos is frequent as it allows to attract potential business opportunities. Moreover, the different activities like cinema, bowling and nightclubs contribute to give a trendy and lively reputation to the neighbourhood. Finally, the Flon and its architectural style, combining modern and vintage, is a welcoming place for visitors from all over the world.

4. Methodology

The first step in the process of collecting data was to choose a subject and a region to study. We quickly agreed on the exploration of the neighbourhood of Flon, for its easy access and its interesting placement near the commuting accommodations. As Flon is a commercial neighbourhood, we decided to focus on commercial signs. The data corpus is mainly composed of window displays and brands’ logos. We went there a first time in order to take pictures of commercial signs present in this neighbourhood in at least two different languages. Later on, we came back and took more pictures and decided to extend our data collection to semi-directed interviews with owners or employees of a selection of commercial centres either restaurants or shops. Semi-directed interviews were chosen because they offer a clear and direct response to a set of questions asked, and also, the respondents could speak more widely and answer in more detail. We formulated the following questions with the intention to ask more general aspects about the use of languages by the sellers and gradually asking them specific questions about the use of English in their signs. The interviews were conducted in French because of our assumption that not all the sellers would speak English and because it is the official language of the canton. Their decision to open a commerce in Flon was a piece of information that we considered important because of the potential commercial opportunities.

- Do you speak English?

- What languages do you speak?

- Why did you choose to have your logo/sign written in English?

- Why did you choose to open a shop/restaurant in this neighbourhood?

- What value does English have for you? E.g. commercial, touristic, trendy, international, etc.

The questions above are translations in English of the French questions that we originally asked. The transcription of the answers was done via paper-pen. Afterwards the answers were rewritten in a Word file.

Finally, we selected a corpus of data composed by pictures from 9 shops and 3 restaurants. The criteria of selection have been the presence of English in brand names. It also considers the sellers’ responses to the 5 preceding questions. Among the 12 sellers interviewed, 5 of them speak English and define their level as a B2-C1. This level was acquired in high school. 2 of them are fluent and 3 sellers do not speak English. Referring to the second question, 10 sellers are multilingual and speak at least 2 languages (German and French most frequently). The selection of data was done according to brand logos that used the English language. All the data collected has received approbation to be used by the sellers. They were informed about the study we conducted and the scientific purposes of the collected data. The discussions lasted 10 minutes on average and were conducted in their shops/restaurants the 19thof December 2018.

Taking pictures was the easiest part. When interviewing the sellers, we proceeded as if it was a dialogue. Each researcher asked one question at the time. Rephrasing was sometimes needed for the better understanding of the questions by the sellers but also because they asked us directly to rephrase the questions and be clearer. For example, the question “What value does English have for you?” needed to be rephrase as “In which context is English valued according to you?” or “What is the importance and the meaning of English for you?”. It was difficult to write the given answers while asking questions. Moreover, the device used to collect data was uncomfortable. One of the difficulties we faced was the refusal or the reluctance of some sellers to address our questions especially in restaurants. As a consequence, we had to search for other restaurants/shops which took us more time. Finally, we succeeded in collecting data about our questions and about our initial questioning.

5. Results

For our analysis, twelve pictures were selected out of our data corpus. These signs were produced top-down by the business owners. Out of those 12 commercial signs including the shops’ names and brands, 8 are exclusively in English and 4 in both English and French. However, the schedules on the window display are always written in French as well as prices, e.g. picture 2.

Picture 1: Green Van Company window display (French schedule).

Picture 2: The Next Cut Barber Shop window display (information about prices in French).

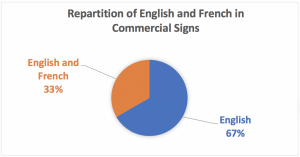

Figure 1: Repartition of English and French in Commercial Signs.

The distribution of languages is not equal, 8 signs are monolingual in English (67 %) whereas 4 are bilingual (33 %). Most monolingual window displays are accompanied by images. Picture 1 is a burger restaurant, even if the sign and the information are in English, the client can understand what type of product is sold there, by looking at the images. The same goes for picture 2, even if the client does not understand what is said in the sign, the image of hair makes it clear. For picture 3, there are no images but the written sign “Cosmetics Obsession”, which assumes that the client knows about what it is since these words resemble to French.

Picture 3: Cosmetics Obsession sign.

Picture 4: Pompes Funèbres sign.

Picture 5: Pet-station sign.

In bilingual signs, it is interesting to denote an interlingual wordplay. In picture 4, the owner uses the wordplay of a funeral parlour in French (pompes funèbres) and the use of “pompes” in jargon which means shoes. The presence of a shoe image and the explanation in English below, “the shoe store”, are tools for the customers to understand. The same wordplay can be observed in “Pomp it Up” (cf. Appendix). In picture 5, the owner also used an explanation in French.

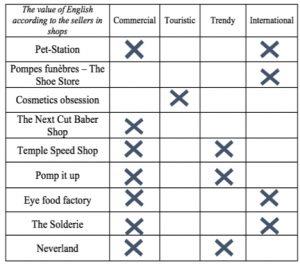

According to the interviews we conducted, most of the sellers responded to the first question by saying that they had a level of English that was enough to understand and be understood: “on se débrouille” [we get with it, we do with it] was the main sentence that we came by when asking this question. The Green Van Company owner has a “perfect” English (as reported by himself). Temple Speed shop has very little knowledge of English as well as The Next Cut Barber Shop and Neverland. Among the other languages spoken by the sellers, besides French and English (for some), we find Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Arabic, Albanian, Turkish, Kurdish, Italian, German and Swiss German. The questions 3 (“Why did you choose to have your logo/sign written in English”) and 5 (“What value does English have for you? E.g. commercial, touristic, trendy, international, etc.”) are linked. The respondents often answered one question by the other and inversely. More specifically, for question 3 people tend to answer that they did not find an equivalent of what they tried to convey in French or another language to use, so they choose to have an English sign. For example, the owner of Pet-station could not find an equivalent in French, he states: “animaux-station is not attractive, and it is longer”, the English version better suits the idea of his shop. When asked about the value of English a majority of 7 respondents give to the English language a commercial value while 3 respondents argue that it has a trendy value. The English language is considered to be international by 4 participants. Only 1 participant thinks that English assumes a touristic value. A majority of 7 sellers use the English language in a trendy way and 2 of them also add commercial purposes. The commercial purposes are mainly coupled with other reasons such as trendiness and a touristic factor.

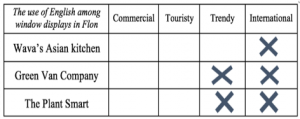

Table 1: The value of English according to sellers in shops.

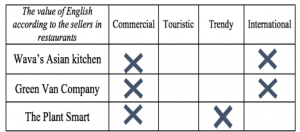

Table 2: The value of English according to sellers in restaurants.

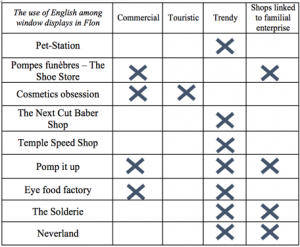

The answer to question 4, about the situation and emplacement of the store, was that all the participants agree on the commercial opportunity of being situated in Flon though different aspects: the proximity to public transportation and the number of customers in the street. The proximity with other shops also needs to be considered knowing that 4 shops are family businesses (Table 3).

Table 3: The use of English among window displays in Flon.

Table 4: The use of English among window displays of restaurants in Flon.

6. Discussion

As seen in the previous section, several results emerged from the pictures and the interviews. The aim of this paper is to focus on the use of English as a lingua franca in this neighbourhood through observation of window displays and brand logos, in order to highlight the values and purposes given to the English language in commercial signage. According to the results, the use of English as a lingua franca does have commercial value. Indeed, table 1 shows this purpose. However, in practise and in the conception of the window displays, only 4 of the participants really use it as such (cf. Table 3). It contrasts with the first hypothesis of this research, which considered English to have commercial value and purposes for the conception of shops’ names. After interviewing the twelve participants, it appeared that English was used in a trendy way such as expressing a concept/name, which couldn’t be translated. The use of English here is almost an evidence for the sellers and it can be considered as Englishization (Görgülü 2018; 139). “Foreign elements and English lexical items influence the naming of store signs in the language” (Görgülü 2018: 140). Moreover, the brand names and slogans of those shops are mainly in English and they encapsulate the philosophy of a brand (Piller 2001; 160), e.g. Temple Speed Shop. This is considered by Piller as the proof of English as global lingua franca that everyone is able to understand or speak. But the interview results show that there is a difference between what we see on window displays and what the sellers really think. Many owners did not think about the global aspect of English and did not think of it as a tool to attract tourists. They do not consciously recognise in their speech that English is a global language, but they say that English is everywhere, it surrounds them so it was evident to choose an English branding name.

In addition, the contrast between the use of English on the window display and the actual knowledge of this language by the owners can be drawn. Owners of Neverland and Temple Speed Shop do not speak English. It refutes Piller’s argument about the global usage of this language as to make communication processes easier. In addition, Lüdi’s case study can be reflected through the Flon. Even if the owners do not speak English and that English is used only for commercial purposes or because everyone uses it, the fact that all the schedules and the information are given in French, shows that the English language serves because of its “high visibility” while French is used to “convey the meaning” (Lüdi 2001: 62).

In restaurants’ commercial signs, one interesting aspect is that it reveals the philosophy or the concept of the restaurant which cannot be translated into English. But also, it denotes that those three different restaurants are connected with the North American culture, e.g. Green Van Company with burgers and Plant Smart. The owners directly explained that this was a concept which found its origin in an English-speaking country or that the concept could not be translated. When considering Wava’s Asian kitchen, it brings to an interesting phenomenon, since Asian restaurants are nowadays present in every country. It is the globalization of the Asian restauration. The owner himself explained that it was obvious to have English for Asian restaurants since it was a global phenomenon. Finally, all the restaurant owners agreed on the fact that their customers are mainly Anglophone clients, even if they do not target this clientele specifically. For example, Wava’s Asian kitchen targets students who will transmit their impression to others, and focus on the “bouche à oreille”. The international food selling in Wava’s Asian kitchen also targets foreigners, whereas, Green Van Company and Plant Smart try to attract local customers.

Finally, shop owners accord little importance to commercial or touristic value to the English language (cf. Table 3). Moreover, restaurant owners think that the English language does not have a commercial use in Flon (cf. Table 4). Therefore, we can see the difference between the two kinds of sellers selected and the similarities: almost every shop and restaurant use the English language as a trendy tool to fit in the fashionable Englishization of the world.

7. Conclusion

The neighbourhood of Flon is full of multilingual aspects to examine. The analysis of data has revealed the dominance of English in commercial signs over other languages, including the official language in the canton. There are a lot of differences between what we assumed at the beginning of this study and what we discovered. It would not have been possible without interviewing the different sellers. Talking to the sellers allowed us to see more differences and to reveal more dimensions to the use of English in Flon, such as the linguistic landscape and the soundscape. Indeed, as described in our hypothesis, the sellers give to the English language a commercial value but do not explicitly use it for this purpose. Some limitations of our study are that we focused on a corpus of only 12 pictures, which is not representative of the neighbourhood. Our study is not representative of the linguistic landscape present in Flon since we only chose the signs that featured English. Thus, it could be interesting to further investigate the linguistic landscape of Flon by considering all the languages present there. Our study demonstrated that English is used a lingua franca in Flon. It also allowed us to see that there is a difference between what the sellers tell us and what the landscape tells. Therefore, the main value given to this language by the sellers is commercial but its actual use in Flon is most importantly trendy.

8. References

Blommaert, J. Collins, J. Slembrouck, S. 2005. Polycentricity and interactional regimes in “global neighborhoods”. Ethnography, 6(2), 205–235.

Crystal, D. 2003. English as a global language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Görgülü, E. 2018. Foreignization and Englishization in Turkish business naming practices. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies 14. 139-152.

Kaur, P. 2013. Attitudes towards English as a Lingua Franca. Kedah: University Utara Malaysia. 214-221.

Lüdi, G, Höchle, K, Yanaprasart, P. 2001. Pattern of language in polyglossic urban areas and multilingual regions and institutions: A Swiss Case Study. 55-78.incomplete

Mooney, A. Evans, B. 2015. Linguistic landscapes. In A. Mooney and B. Evans (eds.), Language,Society and Power: an Introduction. London: Routledge. 86-107.

Official website of the city of Lausanne. Available on: http://www.lausanne.ch/fr/. Accessed the 20.12.2018.

Official website of the neighbourhood of Flon. Available on: https://flon.ch/fr/. Accessed the 20.12.2018.

Paviour-Smith, Martin. 2016. In S. Knospe, A. Onysko, M. Goth (ed.), Crossing Languages to Play with Words, Section II, Cutting across Linguistic Borders? Interlingual Hair Salon Names in Plurilingual Switzerland: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Berlin: De Gruyter. 231- 257.

Piller, I. 2001. Identity constructions in multilingual advertising. Sydney: University of Sidney. 153-186.

Stotz, D. 2006.Breaching the Peace: Struggles around Multilingualism in Switzerland. Language Policy, 5(3), 247-265.

The Guardian, A Stateless Language that Europe must embrace, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2001/apr/19/languages.highereducation. Accessed the 23.12.2018.

9. Appendix : Corpus of images

Picture 6: Wava’s Asian Kitchen sign.

Picture 7: Plant Smart – Whole Plant Based Nutrition sign.

Picture 8: Temple Speed Shop – Les Essentiels sign.

Picture 9: Temple Speed Shop products advertising.

Picture 10: Pomp it Up sign.

Picture 11: The Solderie sign.

Picture 12: Eye Food Factory sign.

Picture 13: Eye Food Factory entrance.

Picture 14: Neverland sign.