Avenue d’Echallens: A Small Multilingual World Inside Lausanne

Abstract

This paper is focusing on the shop windows on Avenue d’Echallens where a large number of multilingual signs have been found. The purpose of this paper is to understand to which extent these shops use different languages on their windows and which the functions of those signs are, and in which ways they relate to the business. To do so we have not only analyzed and compared the signs but also interviewed the shop owners/employee in order to learn about their shop, their use of multilingualism and the signs on their windows. Talking to them was revealing mainly because we discovered that many signs were not advertising for products inside the shop but aiming at a specific community, promoting events and gatherings. Therefore, those signs are there not only designed for commercial purposes, since some of them also have social purposes. It is showing—just like in Maria Sabaté-Dalmau’s work that is talking about migrant callshop in Barcelona (Sabaté-Dalmau, 2014)—that those places are not only businesses but also places for social interaction.

Introduction

Recently, a considerable amount of literature has been written about the theme of Linguistic Landscape and Multilingualism. As we are living and studying in Lausanne, we thought it could be interesting to investigate its signs, especially as it has never been done before. The objective of this study is to focus on an Avenue in Lausanne called Avenue d’Echallens and to understand the use of multilingualism on shop windows. We noticed that on Avenue d’Echallens, a number of shops from different fields (food, beauty salon, money exchange, religious) are aimed at different communities, with speakers of different languages. We could find a variety of languages on the shop windows, such as Tamil, Albanian, Portuguese, German, Spanish, among others. It may be important to mention that the official language in Lausanne is French. This avenue is not located exactly in the city center, but not on its periphery either. In such a multilingual environment, the question we would like to answer is: To which extent these shops use different languages on their windows? What are the functions of those signs and in what way do they relate to the business? We will try to answer those questions through linguistic landscaping complemented by interviews that we conducted with the shop’s owners/employees. This case study/blog entry will be structured as follows: theoretical framework, the contextualisation of Avenue d’Echallens and the city of Lausanne, the methodology and a final section with the results and a discussion.

Theoretical Framework

The first two important terms to introduce are multilingualism and linguistic landscape because in this paper in order to talk about the multilingualism in Lausanne we will analyse the linguistic landscape of a part of the city. Multilingualism can be seen as a set of resources people have to communicate in any language, may it be in the spoken or written form. The investigation of written multilingualism is also called linguistic landscape, Gorther Durk provides a definition of that term: “The language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings combine to form the linguistic landscape of a given territory, region or urban agglomeration.” (2006:2). He explains that “the data are not meant to indicate the linguistic composition of the city as a whole, but simply as an illustration of the linguistic diversity”. (Durk, 2006:3). It is interesting and easy to study multilingualism through linguistic landscape because it is “the most perceivable sign of diversity for passers-by, so that the Babel of languages and alphabets on display in certain areas, in particular those where immigrant communities are present, immediately perturbs passers-by”. (Helot, 2012: 28).

The fact that Switzerland is a quadrilingual country always calls people’s attention, even though the population do not necessarily speak each other’s language. Georges Lüdi points out in his study the fact that through immigration, Switzerland has become an even more multilingual country (Lüdi, 2008:196). Apart from the official languages which are German, French, Italian and Romansch, the Swiss Federal census in 2000 shows 14 non-national languages which are widely spoken by immigrants in Switzerland. Serbian, Albanian, Portuguese, Spanish and English are some of them. In his study, he wanted to investigate how the country deals with its linguistic diversity. He also discusses the different linguistic landscapes in Switzerland. In Basel, even though all the official signs are in German, many other languages are used for advertising, billboards, commercial shops and private inscriptions, without any translation to German. These signs are usually in English, French, Italian, Russian, Turkish, among other immigrant languages. Another interesting fact is that sometimes different languages are used in the same signs, not as a way to translate the message, but to convey different ideas.

Nikoloau (2017) explored the composition of shop signs in a touristic city in Greece and he discovered that foreign languages were used to suggest a symbolic identification, English was linked to free market economy and languages such as French or Italian were synonyms of prestige. Most of the time, in touristic shops Greek (the national language) was smaller than the other languages and appeared second. He explains that “English appears to be the preferred language of the primary sign which has a more emblematic function, whereas Greek is the language of choice for the secondary sign fulfilling more utilitarian purposes.” (Nikoloau, 2017: 174) which means that “the arrangement of different codes on single signs indicates a tendency to assign indexical or symbolic prominence to languages” (Nikoloau, 2017: 174), such as modernity or prestige. Those discoveries are close from the one Lüdi made (2008).

In another study on language about polyglots urban areas in Switzerland, Lüdi realized that shop signs were “mobilizing the whole range of their resources whilst conforming to the value of each variety, they do not stick to one language on a particular time, but interweave elements of different languages most creatively”. (Lüdi, 2010:62).

Another study that can be relevant for our paper is the one Maria Sabaté-Dalmau conducted on locutorios in Barcelona (Sabaté-Dalmau, 2014). She explained that those shops who were offering money transfers and SIM card to migrants were “testimony to a grassroots reaction against the top-down institutional barriers imposed on migrant populations by a hostile late-capitalist block” (Sabaté-Dalmau, 2014:25). She observed that those shops were also giving a “social infrastructure” (Sabaté-Dalmau, 2014:83) to the migrant helping them to gain their place in the society as they could socialize there and meet people who encountered the same problem as they did. Also because they do not suffer from “digital exclusion” (Sabaté-Dalmau, 2014:33) anymore.

In view of all that has been mentioned so far, one may suppose that the multilingualism on Lausanne’s shop windows is mainly going to be symbolic but could also act as a “language mediators and articulator” (Sabaté-Dalmau, 2014:78).

Contextualisation

The context chosen for this research is the linguistic landscape on Avenue d’Echallens in Lausanne. We noticed that there is a variety of languages used for advertisements in the commerce of this neighbourhood, especially at the beginning of the Avenue which is closer to the city center and bus stops. This is the reason why we chose this area. This Avenue is part of the Maupas/Valency neighbourhood, with about 13’834 inhabitants, which is just 10% of the population of Lausanne.

Figure 1: Location of Avenue d’Echallens in the city of Lausanne.

Map found on : https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/presentation-des-quartiers/02-maupas-valency.html

There are 3887 people who live in the area of Avenue d’Echallens, according to the website of Ville de Lausanne (https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/presentation-des-quartiers/02-maupas-valency.html). It is a region with a considerably large number of foreigners, since 49% of the people living there are not from Swiss nationality. Most of the foreigners come from other parts of Europe, followed by South America and South Asia.

When walking on Avenue d’Echallens, from Park Valency to Chauderon—which is only a small part of the avenue considering its length, we can see a wide range of ethnic shops and restaurants, such as Vietnamese, Italian and Japanese restaurants, Asian grocery shops, Turkish butcher, among others. When going to these grocery shops, the owners are usually from Sri Lanka, but they sell products from Africa, Asia and South America, and different languages can be heard by the customers. The shops in our research are varied, as we analysed windows from food shops, beauty salons, travel agencies and money exchange shops. It is difficult for us to understand the reason why the owners chose to open their shop on this Avenue. According to the results of the interview we had with the staff/owners, most of them chose Avenue d’Echallens because that is where they found a place to rent, only a few chose it because they claim it is a convenient area near the centre and with bus stops nearby. None of them chose this Avenue for ethnic or linguistic reasons.

Methodology

On Avenue d’Echallens we found many different kinds of shops and places that had different languages on their windows. Therefore we just walked around and took some pictures of the shop we thought could be interesting to study. It was surprising because on one small part of that street there were maybe 15 shops with multilingual shops one after the other and then the shop windows were monolingual again. Once we selected our pictures, we decided to go back on this street and asked to shop owners a few questions in order to better understand their use of multilingualism and find out more about the use of languages in this area. These were the questions asked mainly in French but also in Portuguese, especially in the money transfer shops.

1) How long have you been in this area?

2) Why did you choose to come here?

3) What languages do you speak?

4) What languages do you speak with your customers?

5) Where are your customers from?

6) Where do you come from?

7) Why did you choose these languages in particular for your advertisements?

It was really interesting to directly talk to the owners and discover some facts about the conditions of production of the written signs there. The first two meetings did not go really well. The first shop we went to was a “bistrot” and we directly felt uneasy there, everyone was staring at us. The owner then asked us what we wanted and we explained to him that we were students at the university and we wanted to ask him a few questions. As soon as we mentioned the word multilingualism and blog entry he/she said “Non” and explained to us—with a strong accent foreign accent while talking in French—that she/he was not interested at all. He/she seemed scared and was quite disrespectful towards us so we left for the next business. The encounter in the next shop did not go really well either. We entered the shop and waited for the owner to finish with his customer in order not to disturb him/her in his/her business. When we were about to explain him why we came into his shop, a man with a strong African accent entered and started to shout at the owner who had a strong Indian accent. They were arguing about some money they owe each other, something related to dollar currency and not Swiss Franc. As it was quite tense, the owner asked us to come back later. After that, our meetings went well and we could gather the answers we needed to help us in our research. It was surprising to discover so many multilingual shops and signs on that street but also all around Lausanne. Our perception of the city has definitely changed, and we are now more aware of the different languages used by people in different contexts. The city might look limited when it comes to the linguistic landscape at the first glance, but once we start to look at it in more detail, we find languages being used that we would not imagine. It also shows us that more research can be done in this field, as there is still a lot to discover in terms of linguistic landscape in Lausanne.

Results & Discussion

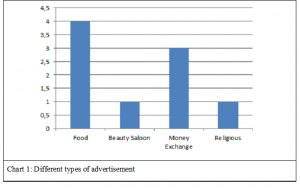

As we have seen, Avenue d’Echallens is a place in the Maupas/Valency neighbourhood with a big quantity of commercial shops. The shops that we are analysing in this research are from different sectors, as seen in Chart 1 below. From the chart, it can be seen that restaurants and food shop are the most numerous types of establishments along with money exchange shops. Those money exchange shops are typical establishments for transnational survival-as in the call shop that Sabaté-Dalmau analysed ((Sabaté-Dalmau, 2014:70).

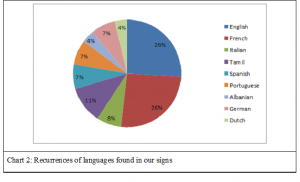

Some of the shops had signs related to their business, and others had signs that were probably placed there by a partner or as a way to advertise another event or product. The languages used are also varied, as illustrated in Chart 2 below:

The languages that occur the most are French and English, but that does not mean that they occur in large quantity. Some of the signs contain a few words in these languages, but the main text in another language.

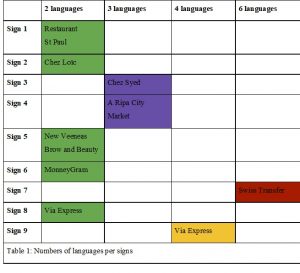

As we can see on Table 1 below, each sign uses a number of different languages. We noticed that the Money Transfer businesses are the ones who use the most languages. Grocery Shops come second, with an average of three languages and restaurants, beauty salon and religious signs are usually monolingual or bilingual.

These restaurant signs shown in Table 2 are bilingual but the reasons for using those languages are apparently not the same. They have their menu written in the signs, but different ways. The Italian one has a translation in French for every dish written in Italian, and it confirms what the owner said about the choice of language. He said that he chose these languages in his sign to advertise what is served in the restaurant, and the use of Italian makes it more authentic and also attracts Italian customers. But he said that most of his customers are French speakers, which explains the use of French, and not English for instance. However, the second restaurant uses a mix of Spanish and French, without necessarily translating them in both languages, which also occurs in George Lüdi’s research. Indeed, they are “mobilizing the whole range of their resources whilst conforming to the value of each variety, they do not stick to one language at on particular time, but interweave elements of different languages most creatively” (Lüdi, 2010:62) This is the place where the owner refused to talk to us, but we have the impression that he uses Spanish and French in quite a random and complementary way, as the restaurant does not seem to be frequented by Spanish or Latin American people and as we do not have the same text in different languages. We could hear people speaking French inside, and they did also not seem to be there to eat, but to socialize.

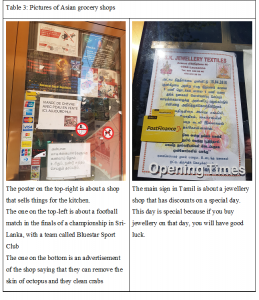

The pictures on table 3 can almost be considered as monolingual signs as most of their information is in one language, only a few details appear in other languages. Most of the posters are written in Tamil, and the picture on the left shows signs referring to things that are not directly related to what the shop sells, except the sign about viande (meat). One of the posters is about a sports team which is significant because it is not for commercial purpose, and the other is about another shop selling something else. When we asked the shop owners the reason why he put those signs there, he explained to us that someone else put them here and that they were not his. This answer has important implications because it means that the person who puts those signs knew that the customers were mainly Tamil— as it has been confirmed by the shop owner—and thus could be interested in that information. Those signs have no direct link to the shop, they are addressing a community in accordance with Maria Sabaté-Dalmau’s finding that those shops provide “migrant populations with a migrant-operated social infrastructure” (2014:83). Therefore those kinds of shops are not only for commercial purposes but they are a place where the members of a migrant community can find information about their own group. The right picture also reflects this idea as it is also located on a grocery shop window but the sign advertises jewellery and it is also aimed to a peculiar audience, in this case Tamil speakers, while the other important information concerning the shop is addressed to any kind of customers. It may be important to underline that there is a visual overlap of signs which may prove that those signs are aimed to different audiences. These findings raise intriguing questions regarding the Tamil community of Lausanne as we find many signs directly addressed to this community in a small area of this street.

On table 4 we can see a sign with two languages, English and French. What surprised us the most was that, the shop sign says it is a beauty salon, but it looks like a textile shop.

When we went inside, there were typical Indian clothes, jewelry and shoes everywhere. On the center of the room there was a woman sewing and fixing “European” clothes and on the corner of the room there was just a chair and a mirror for the beauty services she provided. We asked the lady working in this shop why she chose those two languages for her advertisement and she explained that she could reach a wider audience with English, addressing any kind of customers. It is interesting to see that in this situation the sign is partly linked to the shop, in the sense that it is advertising only one of the services she is providing, the less visible one. The same goes for the shop’s name that is Brown and Beauty.

The sign on table 5 is places on the window of a travel agency, which organizes trips to countries like Albania and Kosovo. They also work as a money exchange office, and their main customers are from Kosovo, Morocco and Africa according to the owner. They usually speak to the customers in French and Albanian but not English. The sign on the shop window has nothing to do with their business, and when asked about the reason for posting it, the owner said he did not know, someone just asked him and he agreed. The sign is about an Albanian Islamic community in Lausanne, and similarly to the grocery shops, the language — Albanian— here is used as a way to attract people from that community, a very specific audience that speak that language. The sign is not translated into French, which confirms even more that the language is not used for commercial purpose or for attracting customers to the shop.

Table 6 illustrates two different money exchange businesses that use different languages in their advertisements, as their target audience is not only people living in Lausanne but also travellers and migrants. The picture on the left shows an agency where most of the employees are South American and speak Spanish. The manager said that most of their customers are from Brazil, Nigeria and Bangladesh. Surprisingly, their sign contains a message in Portuguese, English but not in Bengali. However, it has a translation into Dutch, which is not part of their target audience at all. The agency has other offices in many other countries, that could explain the presence of languages in the signs which that are not related to the local community or target audience. The sign might be standardized for all the shops. As for the second money exchange agency, the employees are all Brazilian, and we arrived the customers and the staff were all speaking Portuguese. The agency has other offices in Switzerland, but apparently not abroad, which explains the use of the Swiss official languages on one of the signs. Most of the clients are from Brazil, South America, Switzerland and Portugal, reason why they also use English, and have one sign mainly in Portuguese. The manager said that the use of different languages in the signs are to attract new customers, similarly to the first money exchange shop.

Conclusion

It was the aim of this study to investigate the linguistic landscape on Avenue d’Echallens in Lausanne. We discovered that various shops use different languages and not necessarily French, which is the official language in Lausanne. The signs are not only used to attract customers to their shops, but also as a way to advertise events or other local businesses related to a specific diasporic community in the city. Our results confirm that not all the signs are directly related to the kind of business they run, but some shops are used as a vehicle to give other information to a particular community, such as the sign for the final of the football sports’ team Bluestar Sport Club. Concerning the translation of some signs into the local language, this current study seems to conform with previous studies, the use of different languages on one shop windows does not mean that one sign is translated in various languages. Indeed, the main tendency is to link each languages to a peculiar content. this study helped us confirm that the linguistic landscape of this Avenue is varied, which shows that Lausanne is also a multilingual and multicultural city. It would have been interesting to study more other neighbourhoods in and out of the city center to compare the data and see if there is a difference in the number of languages used in shop signs. Moreover, it would be interesting to study the linguistic landscape of other Swiss French-speaking cities to be able to compare the results to the ones we obtained in Lausanne and try to understand the use of different languages in these contexts.

Bibliography

- Gorther Durk, 2006, Linguistic Landscape: A new Approach to Multilingualism, Multilingual Matters.

- Helot Christine, Barni Monica, Janssens Rudi, Bagna Carla, 2012 Linguistic Landscapes, Multilingualism and Social Change, Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Lüdi Georges, 2008, Mapping immigrant languages in Switzerland, Mapping Linguistic Diversity in Multicultural Contexts, Mouton de Gruyter, p.196-215.

- Lüdi George, Höchle Katharina, Yanaprasart Patchareerat, 2010, “Patterns of language in polyglossic urban areas and multilingual regions and institutions: a Swiss case study”,. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, January 205, 55-78, Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/view/j/ijsl.2010.2010.issue-205/ijsl.2010.039/ijsl.2010.039.xml, Accessed on: 11.05.2018.

- Nikolaou Alexandre, 2017, Mapping the linguistic landscape of Athens: the case of shop signs, International journal of multilingualism, 14, 2, p.160-182, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2016.1159209 , accessed on: 23.05.2018.

- Sabaté I Dalmau Maria, 2014, Migrant communication Entreprises, Regimentation and Resistance, Multilingual Matters.

Websites

- https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/tableaux-donnees.html

- https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/population/langues-religions/langues.html