By M. Florencia Cuadra and Eva Bouhana

Abstract

This study investigates the linguistic landscape of the area of La Riponne in the city of Lausanne, Switzerland. Through the collection of pictures of multilingual signs in the area, we observe how the confluence of a variety of social groups affects the linguistic landscape. We identify several social processes influencing the diversity of the linguistic environment, namely tourism, gentrification and migration, and notice how languages convey different values within the same space, depending on their producers and visibility. Additionally, multilingual signs present in the area index an opposition between official, prestigious languages and migrant languages, as well as between official, top-down discourses and alternative voices in transgressive signs.

- Introduction

As part of our linguistic landscaping research, we chose to study the Riponne area, which is located right in the Lausanne city centre. From local residents to international tourists and migrants, from students to drug addicts (24 Heures 2016), the Riponne area offers an extraordinary cultural and social mix in different spaces, all in close proximity. Based on a corpus of multilingual signs photographed in this area, we were interested in observing how the confluence of people from very diverse social backgrounds shapes the linguistic landscape of the area, with alternative signs emerging alongside the official signs. This research will specifically analyse what languages official and alternative discourses use and what values are associated with these languages in both types of discourse. Firstly, we will go over various theoretical concepts relevant to our analysis. Secondly, we will give some statistics about the Riponne area in order to contextualize our research. Thirdly, we will analyse the results of our research and highlight how tourism, migration and gentrification shape the linguistic landscape. Lastly, we will make some concluding remarks and provide future research directions.

- Theoretical framework

The study of linguistic landscapes (LL henceforth) has been used as a tool to analyse the social diversity present in a given time and place. As a departing point, LLs have been defined as the set of written signs within public space (Backhaus 2007), such as posters, noticeboards and graffiti, among others, which may be part of both official and informal discourse (Landry & Bourhis 1997). Mooney and Evans (2015) further categorise these signs as either “top-down” when produced by an official government agency or the owner of a building or shop, or “bottom-up” when produced by individuals or groups. The authors also make the distinction between four types of discourse, these being regulatory (used to portray official indications or prohibitions), infrastructural (used to refer to a city’s infrastructure), commercial (used in marketing), and transgressive (used intentionally or accidentally to violate the semantics of a place). Additionally, Lefebvre (1991) highlights the set of relationships that occur within a place and how both social interactions and space shape the configuration of each other. One way these set of relationships can be studied is through what Coulmas (2018) calls city language profiles, which proposes a consideration of the language diversity within a specific area, assessing how social and linguistic variables interact.

Among the many language choices in LLs, two types can be highlighted in relation to our study: the use of English and the use of migrant languages within different types of signs. On the one hand, Piller (2001) argues that English in advertising is not only vested “with the meaning of authority, authenticity and truth” (p. 160) but also linked to internationality, the future, success, sophistication, and fun (p. 163). On the other hand, the use of migrant languages within ethnic businesses is a topic explored by Sabaté i Dalmau in her article about locutorios, i.e. migrant-tailored call shops, in Spain (Sabaté i Dalmau 2013). In order to bypass the legal, economic, and language barriers, these highly multilingual sites run by and for immigrants, provide various services in the language of their customers.

Going back to the topic of interactions between space and language, Blommaert, Collins and Slembrouck (2005) introduce the concept of interactional regimes, understood as the range of behavioural expectations, including language. Each space may have its own type of regime: either an ‘old’ one challenged by ethnolinguistic diversity (e.g. official institutions such as museums that use official languages prominently but have to accommodate to other languages too), or a ‘new’ one springing locally from contact, usually not supported by governmental institutions. When referring to the types of spaces created by the two regimes, the authors talk about monologic and dialogic places, wherein the former impose single regimes and are often monolingual, and the latter allow for multiple regimes to be present in one space, often translating into multilingualism.

The relationship between space and language becomes evident in the phenomenon of gentrification, which is bound to cause a modification on the LL. However, as cited by Papen (2012) referring to Ben-Rafael et al. (2006), the LL not only maps the population shift, but also allows for this shift to happen, attracting more businesses that can appreciate the modernity of the city. At the same time, however, other voices can emerge in protest of such phenomena, which is also reflected on the LL. Overall, considering past research on language landscaping will be useful in analysing our own corpus of data and in discovering the way social interactions and language choices influence one another in our chosen area of study.

- Contextualisation

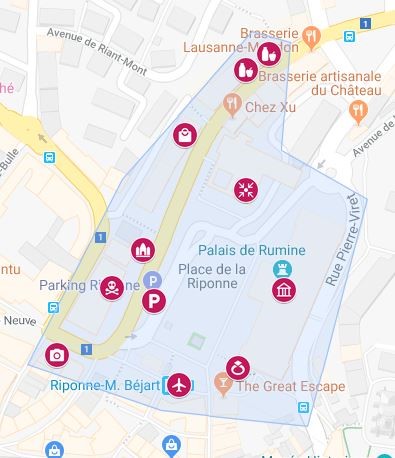

Located between the immigrant neighbourhood of Tunnel and the touristy pedestrian streets of the city centre, the Place de la Riponne is a social, cultural, commercial and transportation hub at the heart of the city of Lausanne, in the area called “Centre”. The Centre area accounts for 38% of jobs in Lausanne and for 9% of the population, while the sub-area of Riponne-Tunnel alone has a population of 1102 inhabitants, out of which 853 are between 20 and 64 years old (Ville de Lausanne 2018). The area delimited on the map below will be the focus of our study (the fuchsia icons indicate the sites where the pictures were taken).

Map 1: Map of the present linguistic landscape study

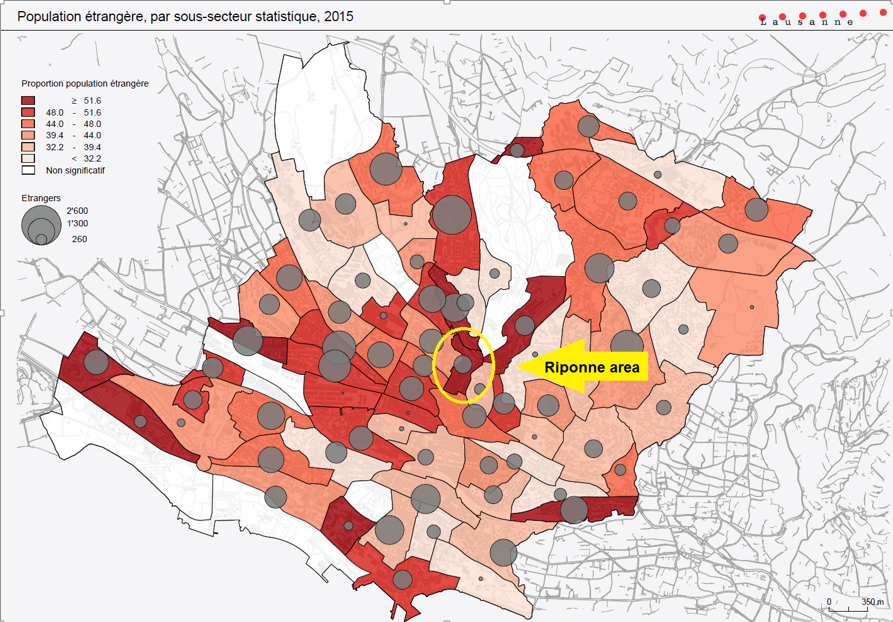

Map 2: Map of Lausanne, highlighting the position of the Riponne area

The square is bordered by the Palais de Rumine (which hosts four museums and a university library) on the western side; by the municipal administration and the local police station on the northern side; by the cultural venue Espace Arlaud, a post office and a labour union branch office (UNIA) on the southern side; and by a commercial street called Rue du Tunnel (close to the immigrant neighbourhood of Tunnel) on the eastern side. Additionally, the Riponne Square contains one of the largest covered parking lots in Lausanne (with a capacity of 1190 places), as well as a metro station just two stops away from the Lausanne railway station.

A major place of transit, attracting a varied population of local residents, international tourists and students due to its transportation and cultural options, the Riponne square hosts a popular marketplace on Wednesday and Saturday mornings, as well as regular flea markets and festivals. It also gives access to touristy pedestrian streets and squares (including Rue Haldimand, Place de la Pallud, Rue Neuve, Rue de l’Ale) of the city centre, with their many shops, restaurants and cafés. Another popular hang-out place is the bar called “The Great Escape” (which overlooks the square), always crowded on Saturday evenings. In the summer, a trendy bar also occupies the northern side of the Place de la Riponne, in the area called La Grenette.

Finally, we should also note that the Riponne square has had a bad reputation in Lausanne and is known for being a hub for homelessness and drug abuse. There have been regular complaints regarding insecurity in the area, which is why the presence of the police has been reinforced (24 Heures 2016).

- Methodology

As part of this research, we found the Riponne area to be an interesting place to investigate since it presents a rich mix of populations and linguistic variety, being central to commerce and tourism. From the graffitied wall of La Grenette to the steps of the official Palais de Rumine, we wanted our corpus to reflect the multiple facets of the Place de la Riponne, which is why we took pictures of multilingual signs in different locations in and around the square, including in the parking lot, next to the subway entrance, inside the Palais de Rumine, and in the adjacent commercial streets. To see the specific locations, please refer to our collective Google Map, where all pictures have been classified according to specific criteria such as the main and secondary languages used, the type of discourse used, the type of medium and the related activity domain. Our pictures are marked by fuchsia icons (as on the map above).

In total, we selected twelve pictures for analysis, which were meant to reflect various social processes at work in la Riponne such as:

- the gentrification of the square, especially towards the south of the square, with shops trying to attract a well-off, international clientele

- the influence of tourism, especially in official institutions like the Palais de Rumine and in advertisements

- the role of migration, visible on the shopfronts of ethnic businesses, but also in bottom-up messages in the form of private ads or subversive posters against authorities

- the surfacing of alternative voices within the area, seen in the graffitied walls

Our objective was to show how various written messages and voices (with varying degrees of visibility) intersect, overlap or clash in a single neighbourhood, sometimes even on a single board, thus revealing the tensions and transformations this area is undergoing.

Even though we both knew the Riponne area from our own experiences, this research was an interesting process as we started paying attention to signs we had never seen before and looking at familiar places with fresh eyes. Besides, we also had the opportunity to discuss with the shop clerks of one of the ethnic businesses we photographed, as we could not identify the language on the window front (which was in fact Amharic). The research raised our awareness about the complex “profile” of this neighbourhood due to the confluence, over just a few thousand square meters, of people from many social and cultural backgrounds, and their written signs evoking different ideologies. As these people cross paths or live alongside one another, sometimes without even realizing it, the signs around them bear traces of their presence, revealing a cohabitation of sorts between the most diverse populations.

- Results and discussion

All twelve photographs depict multilingual signs that feature messages in two to five languages. French (as the official language of Vaud) is used in all twelve pictures, while English (mostly used as a lingua franca) is present in all but one. The other languages represented on the pictures are German (another official language of Switzerland, but not of the Canton of Vaud); Amharic, Spanish, Portuguese (all three as migrant languages), Chinese (in a poster promoting the exhibition of a Chinese artist’s work) and finally Vietnamese (language of a travel destination).

In order to analyse our data, we decided to regroup it by types of signs (shopfronts, institutions, advertisements and transgressive signs) to identify similarities and differences so as to see how alternative bottom-up voices emerge alongside official, top-down discourses.

5.1. Shopfronts

The two pictures below illustrate the contrast between the commercial strategies of two types of businesses located on the Rue du Tunnel, which borders the Riponne square. Picture A shows an ethnic grocery shop where Spanish is the predominant language, while Picture B shows a Swiss bag store.

Picture A, La Tienda de La Esquina store front

Picture B, Qwstion store front

We found it interesting to set these two pictures in opposition to illustrate two co-occurring social processes taking place in La Riponne: the impact of migration versus the gentrification of the area. While ethnic businesses promote the language of their community (here Spanish), targeting a specific clientele of migrants speaking their language, Swiss shops build on the prestige of the “Swiss-made” label and mix signs in French and English in order to target an international, well-off clientele. Connecting this with Piller’s research on the values of English in advertising (Piller 2001), we can deduce that the latter type of business uses English as a way to construct an ideal customer, that is a young, future- and success-oriented, sophisticated and fun. This also transpires in the message written on the shopfront, which puts an emphasis on quality, contemporary designs and the use of sustainable materials. The idea of English as the language of modernisation and progress is very clear in this bag store, even when French is the de facto primary social language in the Riponne area, as well as in the rest of the city of Lausanne. The depiction of such values on shopfronts attracts new businesses that can see the global identity of the city, while fuelling the process of gentrification (Papen 2012). On the other hand, the use of migrant languages on the ethnic businesses’ shopfront is an example of an alternative voice coexisting alongside the use of the official Vaud language and English as a lingua franca, thus indexing locality and globality in the same space.

Interesting to note is that ethnic businesses using migrant languages are more present towards the northern side of the Rue du Tunnel, going towards the Tunnel area, which is an immigrant neighbourhood (Ville de Lausanne 2018) while shops like the Qwstion store, using multilingual messages in French and English, are rather located on the southern side of the Riponne area, close to the more tourist city centre.

5.2 Official institution

We took two pictures inside the Palais de Rumine depicting multilingual signs that reflect the multifunctionality of the building, which hosts four museums and a university library. Picture C below features the entrance steps of the museum, with an official, top-down message designed to entice people to continue their visit. This sign reflects the official language policy of the museum, which uses French as the official language of the canton in larger characters, then German as the most widely spoken official language in Switzerland and then English as lingua franca for the rest of the visitors who speak neither of these languages. We should also note that Italian, the third official language of Switzerland is not present at all, which may indicate that the Italian-speaking linguistic community is a minority in Switzerland and not considered big enough to add a translation into Italian.

Picture C, entrance steps of the Palais de Rumine

Picture D was taken in the same building, just up the stairs from picture C, in the outer room leading to the entrance of the university library. As opposed to the latter picture, here the personal ads left on the board by private individuals are clearly bottom-up and reflect the whole range of languages spoken in Lausanne. French, the official local language, is the most visible language on the wall, in terms of size and prominence, but other languages are also represented, including German (another official language of Switzerland) and migrant languages such as Spanish, Portuguese and English. Looking at our analysed space from Blommaert et al.’s perspective (2005), it is interesting to see how a single building can mix various interactional regimes: the official top-down language policy of the museum designed for tourists, and alternative, bottom-up messages posted by and/or targeted at people frequenting the building, reflecting the impact of migration in Lausanne. The various linguistic signs index the dialogic practices in place in the Palais de Rumine, due to the touristic, academic and social function of the museum, where lots of visitors from both within and outside Switzerland (tourists, local residents, Swiss and international students, etc.) converge for various purposes.

Picture D, noticeboard in the library

5.3. Advertisement

Both pictures below are advertisements that portray the authoritative voice, i.e. the message that catches the eye (Piller 2001), in a foreign language rather than in French. In Picture E, located inside the Riponne parking lot, the English text “Events” dominates the panel, even though the subtitle “À ne pas manquer” (“not to be missed”) is in French and the events descriptions of the 4 Vallées ski resort are in both languages. In Picture F, from the Swiss airline Edelweiss and located at the metro entrance, a centrally aligned text in Vietnamese occupies most of the ad, with only the practical information in French. Two different commercial strategies can be identified here through the use of multilingual messages: on Picture F, the foreign language (written with a foreign script and unlikely to be understood by the local population) is meant to evoke exoticism and entice customers to travel to Vietnam to experience a change of scenery, while on Picture E, the use of English, the international lingua franca, is there to be understood by and attract an international clientele, building on the prestige and fun associated with the English language (Piller 2001).

Picture E, 4 Vallées advertisement

Picture F, Edelweiss advertisement

The two commercial strategies are shown through the use of multilingualism. However different, both ads promote a specific product and construct the identity of their targeted clientele. While Edelweiss is a Swiss company that targets a local clientele (all practical information is in the official local language), the 4 Vallées resort ad uses a mix of French and English in order to target a larger clientele, both local and international. Both ads reflect the impact of mobility in La Riponne, since they are strategically located in places of great transit, and of tourism since both ads entice customers to travel, whether inside or outside of Switzerland.

5.4. Transgressive signs

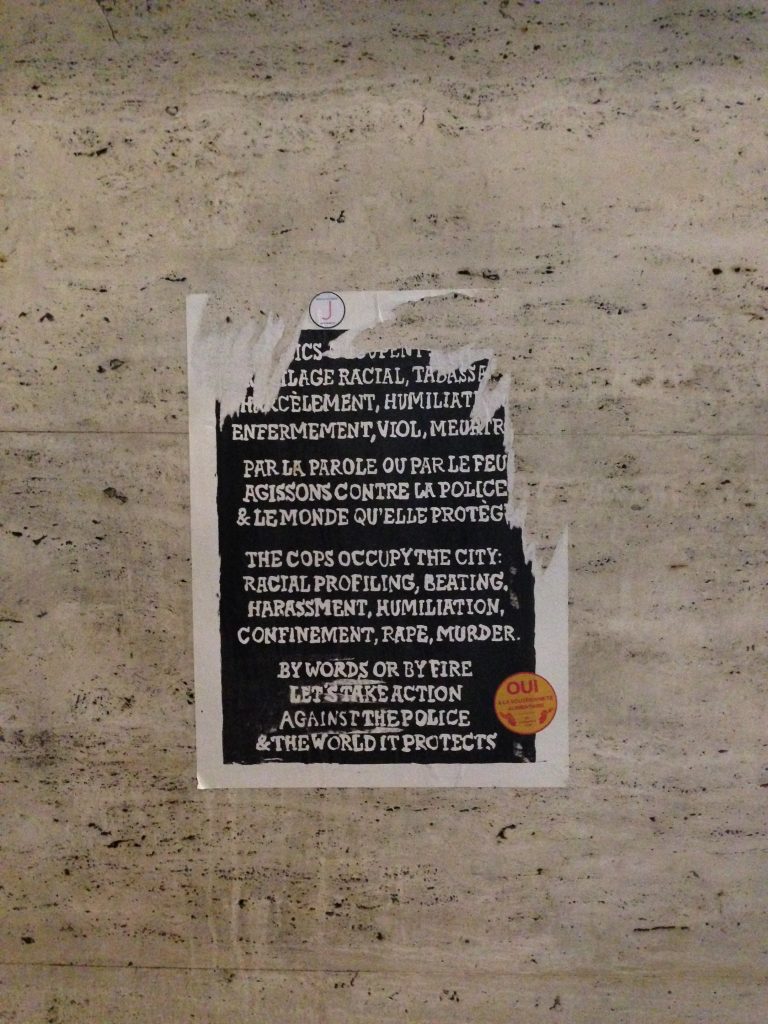

The two pictures below are of transgressive, bottom-up signs that use public, top-down urban facilities as a medium of support to express their opposition. Picture G shows a poster against the police on a wall in a bordering street and Picture H shows a graffitied wall located on the Riponne square. Both signs use French as their primary language and some English as secondary language. On picture G, the translation into English as lingua franca, could be a method to make the anti-authority message accessible for more people. Although the poster is not signed, we can arguably assume that it was produced by members of social movements in favour of migrant rights, following the recent death of a Nigerian migrant in police custody in Lausanne (20 Minutes 2018). In this context, the use of English on the anti-police poster could be understood as part of a wider global discourse of protest against the police that has been spreading around the world, especially on social media, following widespread scandals about police brutality (e.g. in the USA).

Picture G, anti-police poster

The values associated with English on the graffitied wall in Picture H are different. Here, most graffiti, whether in French or in English, reveal an idealistic vision of society (e.g. “peace and love” or the crosswords in French including verbs like “love”, “believe” or “dream”). Thus, English is arguably used to reproduce the words of the hippie movement of the 1960s, and therefore indexes an alternative global discourse about society, advocating for a lifestyle outside of the mainstream consumer society and probably opposing the gentrification of the area. The fact that there are almost no orthographic mistakes in these messages makes us think that they were produced by people with a certain level of education; however, the area hosts such a mix of populations that it would be difficult to locate the authors.

Picture H, graffitied wall in La Grenette

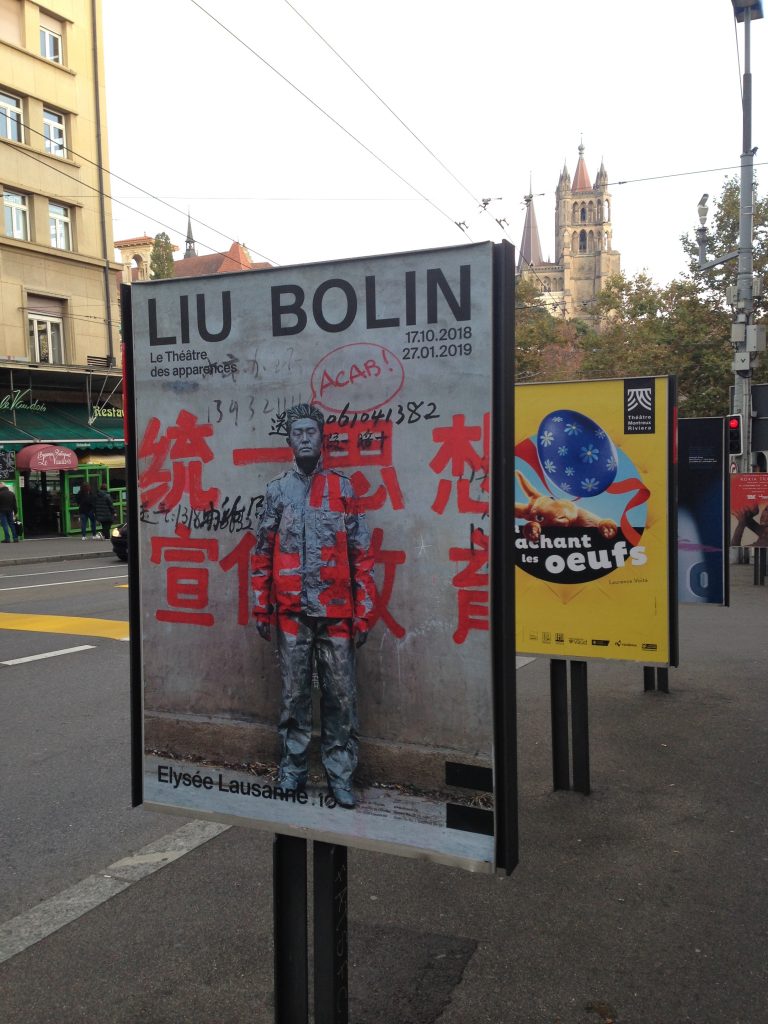

In these transgressive signs, English is used to express the voices of less visible communities, still pointing to a larger international community of alter-globalist social movements. The proximity of these transgressive signs to the local police station and to public facilities adds to their subversive effect and indexes the tensions in the area. Alternative voices do not have any medium of their own to convey their messages, so they just juxtapose their message over existing official buildings or advertisements made by others. For example, on Picture I, promoting the Liu Bolin art exhibition in the Elysee Museum, the transgressive ACAB acronym in non-standard English (meaning “All Cops Are Bastards”) has been drawn as coming from the Chinese artist’s mouth. In this way, the artist is used as a “spokesperson” for the anti-police movement, showing that this discourse transcends borders. Transgressive signs, therefore, add to the diversity of the LL and offer a medium for alternative voices to be heard within the community.

Picture I, Liu Bolin exhibition poster

- Conclusion

This qualitative study on the Riponne area helped shed light at how the inhabitants of the area influence their linguistic space. The convergence of various social groups is evident in the environment’s linguistic landscape, which gives a more detailed view of the diversity of its inhabitants, including Swiss-born residents, migrants, students, tourists and drug addicts. The languages employed by official top-down and alternative bottom-up messages are not necessarily intrinsic to one kind of message, as we saw in our corpus of data. English was used in both types of signs, as well as French. The values associated to English in particular seem to overlap, as both official institution signs and transgressive posters link it to progress, education and internationality, among other such values. The configuration of the Riponne area has allowed for alternative official and unofficial voices to emerge, as visible on the ethnic grocery shop front and the anti-police posters. This not only reflects the impact of migration and globalisation (as seen for example in the fact that the current global discourse of anti-police brutality can find a voice in a local area). It also reflects the varied identities and profiles of the people inhabiting the space, even if they may only be transitory residents (such as students and tourists).

Our sample of pictures aimed at reflecting the many varied practices at work in La Riponne, such as advertisement, business and the emergence of alternative voices. However, we are aware that our data is not necessarily representative of the real linguistic landscape. In future research, special attention should be put on gathering a more representative sample of the area as a whole so that the linguistic landscape can accurately show the frequency of the usage of certain languages, of the types of discourse and signage present, and of the different processes at play.

References

20 Minutes. (2018, September 18). Policiers accusés d’homicide intentionnel. Retrieved December 27, 2018, from: https://www.20min.ch/ro/news/vaud/story/Mike-serait-mort-des-suites-de-son-arrestation-23974624

24 Heures. (2016, September 29). La police va montrer les muscles à la Riponne. Retrieved December 27, 2018, from: https://www.24heures.ch/vaud-regions/police-s-apprete-montrer-muscles-riponne/story/27368614

Backhaus, P. (2007). Linguistic Landscapes: A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Blommaert, J., Collins, J., & Slembrouck, S. (2005). Polycentricity and interactional regimes in ‘global neighborhoods’. Ethnography 6/2, 205-235.

Coulmas, F. (2018). An Introduction to Multilingualism: Language in a Changing World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gorter, D. (2007). The Linguistic Landscape in Rome: Aspects of Multilingualism and Diversity. Working Paper, Instituto Psicoanalitico Per Le Recerche Sociale, Roma.

Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. (1997). Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16/1, 23-49.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Mooney, A., & Evans, B. (2015). Language, Society and Power: An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge.

Papen, U. (2012). Commercial discourses, gentrification and citizens’ protest. The linguistic landscape of Prenzlauer Breg, Berlin. Journal of Sociolinguistics 16/1, 56-80.

Piller, I. (2001). Identity constructions in multilingual advertising. Language in Society 30/2, 153-186.

Sabaté i Dalmau, M. (2013). Fighting Exclusion from the Margins: Locutorios as Sites of Social Agency and Resistance for Migrants. In A. Duchêne, M. Moyer and C. Roberts (eds.) Language, migration and social inequalities: A critical sociolinguistic perspective on institutions and work (248-271). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Ville de Lausanne. (2018). 01 – Centre. Retrieved December 15, 2018, from Commune de Lausanne: https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/presentation-des-quartiers/01-centre.html

Ville de Lausanne. (2018). Cartes thématiques. Retrieved December 15, 2018, from Commune de Lausanne: https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/cartes-thematiques.html