Frassineti Michela and Maksuti Sara

Abstract

This paper explores the role of exotic languages (including English and French) and cultures of restaurants in two opposite areas of Lausanne, namely Ours and Sallaz. The aim of this study is to investigate what languages are employed in a determined space. For this, our paper tries to answer the following research questions: is language linked to space and how?, and why are certain foreign languages used more than others in the city centre? We found that there is a hierarchy between non-official languages used in a particular space, and an inevitable connection between these two, indicating thus a socio-economic factor caused by globalization in terms of economy and a growth in popularity of cultures and their languages.

Introduction

With Lausanne being part of a multilingual country, this city is populated by different nationalities (43.1% foreign population, Demographic Context 2017) other than Swiss people thanks to mainly its well-known universities that attract a great number of students every year. This influx of foreign languages has an impact on local signs, among these restaurants as well. That is why, for this project we took into consideration the neighbourhood of Vallon / Béthusy (we will refer to this as Ours because it is commonly known as such) and the one of Sallaz, where we encountered different types of food service businesses. Furthermore, our aim was to study how languages are strictly related to space and what languages have the most importance in a multilingual city. Indeed, this essay will focus on the following research questions: how is language linked to space and vice versa?, why are some non-local languages employed more than others in the city centre?, analysing commercial signs, namely restaurants, with a special regard to the socio-economic aspect. By observing the language of restaurant signs in two opposite areas, we will, thus, make a comparison between these two spaces. This essay is structured as follows: firstly, we will take into account previous research with a similar concept of languages and space, but in different cities; then we will provide information on the areas we chose and a further presentation of our methodology; concluding, therefore, with a discussion of the results in comparison with the previous researches as well.

Theoretical framework

Considering our field of research, it is significant to highlight that in nowadays societies foreign restaurants are more and more acknowledge by, in our case, the residents of Lausanne. This, due to many factors that include cultural appreciation, the growing popularity of specific cultures, and particularly globalization. This idea is conceived by Appadurai (1996: 10, as quoted in Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck 2005: 206) as ‘vernacular globalization’, that is ‘a grassroots dimension of globalization expressed, amongst other things, in dense and complex forms of neighbourhood multilingualism’ (Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck 2005: 206). By tanking into account the research of Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck (2005), which shows how different languages and their use is organized in different spaces of an immigrant neighbourhood in Ghent (Belgium), we aim to point out the difference between the languages used in distinct areas of the same city, Lausanne, proving thus that “it is obvious that no single neighbourhood can be characterized by one dominant, uniform ‘culture’” (Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck 2005: 207).

Studies like Cenoz and Gorter (2006) have already focused on comparing the linguistic landscape of two different streets, but in two multilingual cities, namely Friesland (Netherlands) and the Basque Country (Spain), thus demonstrating that “the linguistic landscape is related to the official language policy regarding minority languages” (Cenoz and Gorter 2006: 67) spoken in these two areas. Similarly, Lausanne has only one official language which also affects the linguistic landscape of foreign languages (not minority languages). Furthermore, this study proves that the English language does not transmit a “factual information” (Cenoz and Gorter 2006: 70), but rather a “connotational value” (Cenoz and Gorter 2006: 70); sustained by Piller (2001, 2003) as values that are “international orientation, future orientation, success, sophistication or fun orientation” (Piller 2001: 163). Likewise, restaurants have the tendency to use non-local languages in signs in order to preserve their identity and underline the nature of their cuisine. Hence, foreign words do not intend an information but rather a preservation of their culture for an economic profit.

By choosing to focus on the socio-economic aspect of our study, the use of different languages in a specific area depends on the power that a certain language has in that particular space. Indeed, as put forward by Backhaus (2006: 52), “the hierarchy of languages is at the same time an expression of power relations”, consequently proving that unpopular stereotyped languages (Castellotti and Moore 2002: 10) such as Turkish or Hindi have not the same linguistic power as Italian or Japanese in the city of Lausanne. Therefore, we wanted to focus our attention on why certain foreign languages are more popular than others in a particular space, depending on the influx of population of the area, eventually finding a connection between a non-local language and its location.

Contextualization

At first, we wanted to focus only on the neighbourhood of Sallaz and Bessières, but after taking pictures on the street, we were not sure of the type of signs we managed to find because we realised they were only advertisements without multilingual features. Consequently, a classmate suggested to take a look in the neighbourhood of Ours, where we found interesting multilingual signs, the majority of them related to food service. Then, we decided to compare these signs with the ones in Sallaz, where we live.

Our linguistic landscape is based on a corpus of six pictures taken in the area of Ours and Sallaz. The first four restaurants are enclosed in black circles (Illustration 1), all of them located in the same street Rue de Marterey. Likewise, restaurants in Sallaz are enclosed in black circles (Illustration 2): they are both in Place of Sallaz, however, one is more visible than the other.

Illustration 1. Map of Ours showing the four restaurants

Illustration 2. Map of Sallaz showing the two restaurants

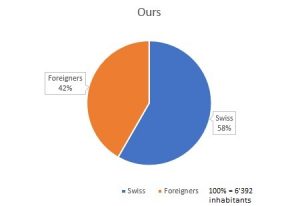

The neighbourhood of Vallon/Béthusy includes Ours, which gives the name to the metro stop (m2, direction Croisettes). This area distinguishes from the others due to the presence of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV), that is the most important employer of the city (Fiche de Population, Vallon/Béthusy 2017). Furthermore, this zone is located in a great position, close to the city centre: by going down Rue de Marterey, it is possible to reach the Cathedral of Lausanne. This neighbourhood consists of the 5% of the population of Lausanne: the 58.3% are Swiss, while the 41.7 % are foreigners out of 6’392 inhabitants, as shown in Graph 1 (Fiche de Population, Vallon/Béthusy 2017). Once stepping outside the metro stop the first noticeable thing is the amount of different food service businesses, such as bakeries, wine shops, bubble tea shops and restaurants as well. Particularly these latter do not offer local food: among these the main types are Italian, Chinese and Japanese.

Graph 1. Percentage of people living in Ours

Conversely, Sallaz is part of the neighbourhood of Sallaz/Vennes/Séchaud, and it is a bigger area with more inhabitants than Vallon/Béthusy, including the 10% of the population (Fiche de Population, Sallaz/Vennes/Séchaud 2017). The metro stop takes the name from this area (Sallaz, m2, direction Croisettes), and it is located in the main square, where mainly lots of food service businesses are present, and other types, too. Among these we can find the optician, the post office, the Kiosk, a small open-air market, a bakery, two supermarkets (Migros and Coop), one Turkish restaurant, one Indian and another we could not identify. The apparent contradiction between these two areas is that the area of Sallaz includes 54.4% of Swiss people and 45.6% of foreigners, out of 14’985 inhabitants, as shown in Graph 2 (Fiche de Population, Sallaz/Vennes/Séchaud 2017). Thus, why are there fewer non-local restaurants in a bigger neighbourhood with more foreigners than in a smaller area with fewer foreigners?

Graph 2. Percentage of people living in Sallaz

Methodology

Our study is based on pictures we took in the interested areas. On the 2nd November 2018, we took a total of 33 pictures of signs in the neighbourhood of Ours and Sallaz, specifically in Rue de Marterey and Place de la Sallaz. Out of these pictures, we only took into consideration the signs that included English and other languages mixed together. However, the pictures we took in Sallaz that day were not food service related, but we decided last minute to make a comparison between food services of this area and the ones of Ours. That is why we could not take the pictures due to personal reasons and the deadline of this project, as we thought about this just before going abroad. Nevertheless, we are completely aware of the food services of the area, since we have lived there for a year now. For our study, we will only use six pictures taken in Ours and Sallaz, respectively four and two pictures. Those pictures represent the only restaurants that can be found in those areas and the only thing these two have in common are restaurants, that is the main reason of our choice. Furthermore, the chosen signs offer a variety of different languages including not only English, but also Italian, Japanese and Chinese. For Japanese and Chinese, help in translation was asked to acquaintances who are fluent in those languages.

At first, we took pictures to everything that was multilingualism related, then we excluded every sign that was not appealing to us, considering, thus only restaurants. This experience stimulated our curiosity because we explored an area (Ours) we had never been to before and we also had the chance to enrich our knowledge of the neighbourhood we live in (Sallaz). For the first area, multilingual signs were easily found, whereas for the second one we had to explore it attentively.

Results

The four restaurants in Ours consist of two Italian and two Asian (Japanese and Chinese) restaurants: the first two show signs in both Italian and the local language, namely French, whereas the other two signs are in Japanese, Chinese, English and French. As for Sallaz restaurants, one is Turkish, named “Istanbul” and their menu has Turkish names for dishes with French descriptions, while the Indian Restaurant only presents the English language in its sign, namely “Indian Curry House”. All these languages and cultures coexist in a multilingual environment as these two neighbourhoods include a high number of foreigners as previously showed.

As revealed by the two graphs of the contextualisation section, the number of foreign people is almost at the same level as the one of Swiss people. Nevertheless, the number of inhabitants of Sallaz is more than twice of Ours. Hence, this difference in inhabitants was contradictory at first. As we have already seen, Ours has a lot of non-local food services but has fewer foreigners than Sallaz which has very few restaurants. This proves once again that space and languages are related and there is a hierarchy between languages that are employed in a specific space and not in another as “not all spaces are equal” (Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck 2005: 202): the closer the area to the city centre (more influx of people), the more mainstream languages (they are the most studied languages in the world, MOSAlingua 2018) such as Italian, Japanese, Chinese are employed; and vice versa.

As for the two Italian restaurants located in Rue de Marterey, they both chose to have an Italian name (“L’antica trattoria” Picture 1, “Bravissimo” Picture 2) in order to keep their identity clear and underline the nature of their cuisine. The Italian language is one of the official languages in Switzerland and a lot of Swiss people speak fluently Italian as it could be also studied at school. Thus, Italian restaurants are known to have a worldwide reputation for their cuisine; as a consequence, it is common to find this type of restaurants abroad, mainly in Lausanne where Swiss Italian speaking people and Italian people come to live for work or university (Piller 2001). Therefore, Italian restaurants are placed in the city centre because on one hand, they are widely recognized and requested, on the other hand, being in the city centre means more economic profit than being in the suburbs. Moreover, in order to appeal to a French speaking community, the technical information regarding opening hours, the type of business and menus are given in French, which has an informational function since it is the official language.

Picture 1. Sign of “L’antica trattoria”

Picture 2. Sign of “Bravissimo”

In order to draw more attention and preserve even more its identity, the restaurant “Bravissimo” used graphic signs like the colours of the Italian flag and drawings of typical Italian dishes such as pasta and pizza. Similarly, both Asian restaurants use respectively a drawing of a fish (Picture 4) to indicate that is a sushi restaurant and Chinese characters (Picture 3) to highlight the name of the restaurant and to appeal to the Chinese community and to the non-Chinese speaking population.

Picture 3. Sign of Chinese restaurant “Nihao”

Picture 4. Sign of Japanese restaurant “Ichiban”

Nowadays, Chinese and Japanese cuisine is gaining more and more popularity in Europe. Especially, Japanese sushi is at the centre of acclaim since it could be perceived as the new Big Mac (Renton 2006). Indeed, this type of restaurant can mostly be found in the city centre as there is a high influx of people who are more captivated by Asian culture and its healthy food. These two restaurants display words in their respective native languages such as nihao (hello) and ichiban (number one) to preserve their identity. Still, as the Italian restaurants, technical information are written in French with the use of an English word that is takeaway: this word is interesting because it does not appear in Italian restaurants as this cuisine, except for pizzerias, does not make food to be taken away, whereas Japanese and Chinese food are known for takeaway.

As for the two restaurants located in Sallaz, they are part of two foreign cultures whose languages are not prevalent in the hierarchy of languages. Indeed, languages such as Turkish and Hindi are not even part of the most popular and studied languages in the world (MOSAlingua 2018). Nevertheless, the Turkish restaurant “Istanbul” keeps its identity with its name and also the name of the dishes that are in Turkish with French descriptions. Conversely, the Indian restaurant sign does not show any hint of linguistic identity as the whole name is in English.

Discussion

The popularity and hierarchy of certain languages is caused by globalization. This phenomenon, as put forward by Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck (2005: 201), “results in increased cultural contact and conflict, increased linguistic diversity and tension, resulting in quotidian and formal public challenges”. Thus, nowadays it is common to find exotic restaurants in big cities due to the constant growth of the reputation and also the acceptance of other non-local cultures. However, there is a clear division between spaces and the languages employed in those as “some spaces are affluent and prestigious, others are not, some are open to all, while others require intricate and extensive procedures of entrance” (Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck 2005: 203) depending on the linguistic identity. That is why, in the area of Ours we found a huge variety of food services including Italian, Japanese and Chinese restaurants; while outside the city centre there are restaurants that are not generally considered as “valuable” because they are not in a strategic position for an economical profit (Mealey 2018). Hence, “the linguistic landscape reflects the relative power and status of the different languages in a specific sociolinguistic context” (Cenoz and Gorter 2006: 67), creating a tangible division between spaces and languages.

Moreover, this separation is clearly conceptualized by the World System Analysis (Wallerstein 1983, 2000, 2001 as quoted in Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck 2005: 201), that sees the world as structured in three parts: centres, semiperipheries and peripheries, establishing a capitalist production. Space and languages are not only socially connected, but also economically. Therefore, this great division could be attributed to cities as well. For example, peripheries have a low economic profit and they completely depend on the centres which rule the economy. Indeed, the “Indian Curry House” restaurant in Sallaz could have a lower level of accumulation of capital than the Japanese one in Ours due to its peripheric position and lower influx of customers. Conversely, semiperipheries manage to have their own high economic profit, still depending on centres’ supremacy. In addition, Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck (2005: 201) claim that “the value of goods from the centres is systemically higher than that of the (semi-) peripheries” which in our study “goods” is replaced by restaurants.

For the first part of our research question, space is inevitably linked to language and vice versa because they both coexist as communication is present in every type of space. Specifically for our study, the economic point of view is the one that has the most influence because, for example, putting an Italian restaurant far from the centre would not be economically advantageous because the influx of population and tourists is focused in the city centre (Mealey 2018).

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to find a link between languages and space as “multilingualism is structured and regimented by space and relations between spaces” (Blommaert, Collins, Slembrouck 2005: 205). Nonetheless, our study had some limitations regarding the restricted number of areas and the limited food service businesses. For this, it would be interesting to analyse all the neighbourhoods in Lausanne in order to widen the number of languages employed and to prove concretely the connection between languages and space in terms of socioeconomics. We also focused our attention only on restaurants, whereas more types of food service businesses could also confirm our findings. Nonetheless, our research demonstrated that spaces and languages are somehow related to each other and there is a visible hierarchy of languages of determined areas due to the growing popularity of these and their socio-economic value derived from economic globalization.

References

Backhaus, P. 2006. Multilingualism in Tokyo: A Look into the Linguistic Landscape. International Journal of Multilingualism, 3:1, 52-66.

Blommaert J., Collins J., Slembrouck S. 2005. Polycentricity and interactional regimes in ‘global neighborhoods’. SAGE Publications, (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) www.sagepublications.com Vol 6(2): 205–235[DOI: 10.1177/1466138105057557].

Blommaert J., Collins J., Slembrouck S. 2005. Spaces of Multilingualism. Language and Communication, 25, 197-216.

Castellotti V., Moore D. 2002. Social Representation of Languages and Teaching. Language Policy Division, Strasbourg, 1-28.

Cenoz J., Gorter D. 2006. Linguistic Landscape and Minority Languages. International Journal of Multilingualism, 3:1, 67-80.

Piller, I. 2001. Identity Constructions in Multilingual Adverstising. Linguistic Department, Language in Society 30, F12, Sydney, 153-186.

Websites

Official statistics of Vallon/Béthusy, on the official website of Lausanne. Available on: https://www.lausanne.ch/de/officiel/statistique/quartiers/presentation-des-quartiers/10-vallon-bethusy.html

Official statistics of Sallaz, on the official website of Lausanne. Available on: https://www.lausanne.ch/de/officiel/statistique/quartiers/presentation-des-quartiers/12-sallaz-vennes-sechaud.html

Article on The Guardian. Available on: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/feb/26/japan.foodanddrink

Article on MOSAlingua. Available on: https://www.mosalingua.com/en/most-studied-languages-in-the-world/

Article on The Balance Small Business on: https://www.thebalancesmb.com/choosing-a-location-for-your-restaurant-2888635