The Power Struggle of Two Discourses: An Analysis of the Linguistic Landscape in La Cité in Lausanne

by Lucie Mottet and Teodora Trujanovic

Abstract

This paper explores the power struggle between two cohabiting types of discourses, regulatory and transgressive, in one neighbourhood: La Cité. With both a quantitative and a qualitative analysis, it presents the old town of Lausanne under a new light. This research analyses how the delimitation of the named neighbourhood is determined by signs, presenting the dichotomy between the capitalistic and anti-capitalistic discourses, such as anarchist and anti-consumerist ones. The interactions between those two discourses illustrate the different constructions of space and shape the neighbourhood. The languages used in those signs also help to understand some tensions between the municipality of Lausanne and its inhabitants. Throughout the paper, the notion of delimitation emerges given that there exist inner boundaries between the spaces where each of the groups have their place to express themselves.

Introduction

“(Social) space is a (social) product” wrote Henri Lefebvre in his book The Construction of Space translated in English by Donaldson-Smith (26). Through this quote, Lefebvre expresses the fact that the delimitation of spaces corresponds to a social construction by ideologies, namely capitalism in our case, rather than to a natural phenomenon. As a consequence, those delimitations are not perceived similarly by every individual which can initiate conflict within spaces.

Among the neighbourhood of La Cité in Lausanne exists a contrast between two opposed discourses; a top-down discourse present in the regulatory signs, particularly in commercial and touristic ones, mainly displaying the strong influence of capitalism and, in opposition, bottom-up signs, namely graffiti and stickers, conveying an anti-capitalistic conception of the space. The power struggle between the two illustrates this notion of socially constructed spaces Lefebvre wrote about. Both discourses evolve in the same space and each one of them is transforming the old town of Lausanne by their interactions within the neighbourhood. These contradictory interactions reveal tensions between these two discourses in the same neighbourhood and multilingual practices tend to contribute and/or influence this conflicting dimension between discourses.

Analysing pictures taken within this neighbourhood will provide us an insight into the interactions between these discourses: how the regulatory and the transgressive discourses cohabit within this space visited by tourists throughout the year. We will start our paper with a contextualisation of both previous researches on the matter and of the neighbourhood. We will continue by presenting both a qualitative and a quantitative analysis of the way those discourses have created space for themselves within La Cité’sboundaries and how a transgression of those limits will generate an erasure of the opposing discourse.

Theoretical Framework

Observing the delimitation of space by looking at the linguistic landscape (LL) allows us to understand the eventual power struggle present in this region. Other studies have been made regarding neighbourhoods and how people cohabit within the space. As quoted before, Lefebvre considers the delimitation of spaces to be a social construction (26) rather than a natural conception, particularly in the context of capitalism in which we live because we are in a society that aims to achieve financial benefits.

Looking at the signs present in a socially constructed neighbourhood warrant us to grasp the power dynamic between the people living there. Trinch and Snajdr outline in their article that “as signs embody different language ideologies they come to shape political, social and economic contexts by conferring differential and competing symbolic and material values on the land” (66). According to them, signs are particularly interesting to look at for understanding the social organisation in a given space because of the different types there are. In this paper, we focus on the comparison between regulatory and transgressive signs. This binary distinction can also be found in terms such as top-down and bottom-up signs. The former defines signs that are on public institutions and announcements which we mostly found in regulatory signs. On the other hand, the latter, which was present in transgressive signs, reports what can be considered as produced by private individuals.

For this research, we will base ourselves on Screti’s round-up of Lefebvrian conception of space: “For Lefebvre, the city is constructed according to, and to reinforce, capitalism and is a space where capitalism is enacted, but also resisted” (2018: 22). We will try to shed light on this dichotomy between the capitalist ideologies represented by regulatory signs and the one resisting it, so transgressive signs.

Next to Lefebvre and its socially constructed space, Ben-Rafael et al. (2006) define the linguistic landscape as the shaping process “of the very scene—made of streets, corners, circuses, parks, buildings—where society’s public life takes place”. By looking at the LL of the city of Lausanne, it is possible to grasp the “sociosymbolic” dimension of the concerned city as well as of the studied neighbourhood, which becomes emblematic of that precise place (Ben-Rafael et al. 2006: 8).

In addition, Ben-Rafael et al. (2006) take into account the great number of actors engaged in this shaping process as public institutions, associations, firms, individuals and many more. The interesting point to focus on is the power struggle and dissensions found in this process between different actors “that do not necessarily act harmoniously” (8), which in our case we hypothesise to be reflected in the dichotomy between top-down regulatory and bottom-up transgressive signs. In order to analyse the space, one has to consider “the era of modernity, globalization and multiculturalism” characterising today’s world, which completely changes the nature, status and population of quarters, neighbourhoods and cities growing in diversity. In this newly contoured space, interactions between public authority and civil society, often characterized as a power struggle, evolve and shape in turn this same space (9). Indeed, power relations act as one of the “structuration principles” building the linguistic landscape (Ben-Rafael 2009, 45-6).

To stick to power relationships, Papen (2012) interprets the space as “one of the arenas where [debates are] taking place (61). The public space is socially constructed through interactions of individuals and authorities, displaying the mainstream ideology, as Lefebvre develops in his work (1991). This propriety of space enables individuals, despite the controlling of state’s authorities, to express their opinions and, as Papen claims, “to disseminate their views” (73). This point shows another facet of LL, “used primarily to shed light on aspects of multilingualism, [that] can be harnessed to seek insights into much broader issues relating to social change, urban renewal, gentrification and its concomitant class tensions” (Papen 2012, 58).

Contextualisation

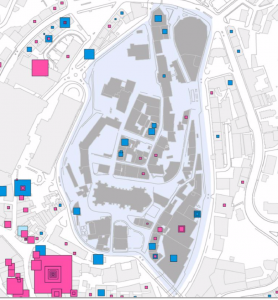

Our paper focuses on the neighbourhood of La Cité in Lausanne, the capital of the French-speaking canton of Vaud. Our choice of this specific sector of the city is based on its touristic nature, as it represents the historical and cultural centre of the city, as well as on our expectations to encounter multilingual practices, in particular featuring English. La Cité is situated in the quarter of Lausanne named “the Centre”, figuring on the map as the number 01 (see appendix Image 11). We observe that its name corresponds well to its centralised localisation. Thanks to the collective Google Mapof the Multilingual Lausanne project, we are able to associate our localisation and boundaries of La Citéwith the one of the official website of the city, here below in Figure 1 and 2. According to statistics found on the official website of Lausanne, La Citécounts 737 inhabitants in 2017. However, this website does not give any information concerning statistics of spoken languages in the area.

While the beginnings of Lausanne were by the lac Léman (lake Geneva), the population moved during the 9thcentury to the hills to what we call La Citétoday. With time, Lausanne was Christianised and started to spread beyond the small section of La Cité, all the way over the “Centre” mentioned previously. The cathedral was officially finished in 1275 and Lausanne became a place of pilgrimage which can be considered as the beginning of tourism in Lausanne. The city continued to grow to what we know today and La Citéremains the historical centre of Lausanne mainly because of its cathedral.

Figure 1: Map of La Cité, found on the official website of the city of Lausanne.

Figure 2 : Our own map of La Cité, based on our linguistic landscaping and data in purple.

Methodology

Our choice of the neighbourhood of La Cité, as previously mentioned, is motivated by its touristic nature considering museums and the cathedral in this area, as well as by our expectations of multilingualism, especially English. Thus, our linguistic landscaping data collection began at the emblematic monument of Lausanne, the cathedral. Then, we stopped by the two museums located in front of the cathedral, the MUDAC (museum of contemporary design and applied arts) and the historical museum of Lausanne (Musée historique de Lausanne). After taking pictures around these touristic attractions, we have continued our search in smaller streets as Escalier du Marché and Rue Louis-Auguste Curtat away from the cultural and historical area. There we found a great presence of transgressive signs, as the map shows (i.e. skull symbols), in the official (according to Lausanne’s official website) border of the neighbourhood. In addition, we encountered many shops, bars and restaurants, considered as a meeting points for its inhabitants.

When dealing with this specific area, we decided to focus on three main aspects that interact with one another as they exist in the same space: signs in touristic places such as museums and the cathedral, commercial signs in activities such as bars and restaurants (places encompassed in capitalist ideologies) and transgressive signs most of which dialogue with top-down signs documented.

After having selected pictures representing each aspect aforementioned, we have evaluated them in reference to the global project of Multilingual Lausanne and therefore, looked for multilingual use in particular. For the purpose of this paper, we have selected pictures that are situated in the south of La Cité, where the two discourses cohabit closely and the power struggle between them is the most visible.

Then, we have uploaded the different chosen pictures on the collective Google Map of the lesson, “Multilingual Lausanne Autumn 2018”. When uploading the pictures, we have categorised them according to these criteria: name, address, authors of the picture, date of collection, presence of multilingual or monolingual practices and considering which are main or secondary languages, the neighbourhood, the support/medium (of the text), activity domain and finally the type of sign (regulatory, transgressive…).

As noted before, we have chosen this specific neighbourhood because of its touristic dimension and the conviction to encounter multilingual practices and especially English as a lingua franca. We were very surprised to notice the negligible use of English compared to French, which is prevalent considering the French-speaking nature of the canton de Vaud of which Lausanne is the capital and its associated legislation policies. Furthermore, it was interesting to observe differently the space, namely as an interaction of signs as well as a construction of these contacts. We were not completely aware of the issues anchored in space when just passing by this area. To “read the space” correctly as Screti mentions in his article by quoting Lefebvre (Screti 2018, 2), we have to take into account “the histories of space and the social practices that occur within it”.

Results and discussion

To compare our different signs, we decided to analyse them on both a quantitative and qualitative analysis to examine and try to understand the coexistence and interaction between regulatory and transgressive signs.

A/ Quantitative analysis

In our selected corpus of 10 images in 9 locations, we count a small number of languages. French is predominantly present. It is found in both regulatory and transgressive signs, in standard and non-standard French respectively. We also found an occurrence of franglais (see Image 8 in the appendix).

While the presence of French was expected as it is the official language of the city, it is the absence of other languages that surprised us, particularly the lack of English. It was indeed mostly used in schedules for touristic attractions as English is considered as a lingua franca and in some transgressive signs, where individuals use English language to emphasize their comments.

We also encountered two other languages: Italian and Chinese. The former was present on the signs for a Pasta bar while the latter was indicating the availability of Chinese audio guides. Those were the only occurrences of those languages we noted during our data collection.

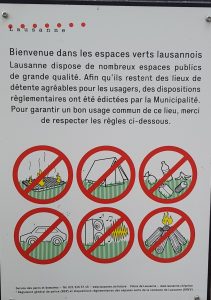

Finally, a number of signs, two in our corpus, were displaying illustrations instead of written texts. In one of our images, the pictures symbolize an assortment of rules to respect in green spaces. The other indicates the direction to take to reach the cathedral. Rather than using the word that might not be universally understood, a sign depicting the cathedral is far more efficient as semiotic signs convey meaning across speakers of different languages.

B/ Qualitative analysis

Throughout the neighbourhood of La Cité, different kind of signs were spotted. Among these, commercial and touristic ones can be considered as signs deriving from capitalist ideologies of Lausanne, since they are encouraging economic transactions and growth of their activities. Signs opposed to those ideologies figuring in the same space tend to be transgressive. These are consequently opposed to the first ones as transgressive additions try to regain control over the neighbourhood by transforming its construction and representation.

Image 1: Pasta Bar Pomodoro della Nonna

As a first step, we concentrate on a commercial sign situated at the entry of the neighbourhood, named Pomodoro della Nonna (Image 1). The sign displayed on this pasta bar is mainly written in Italian. Considering the commercial nature of this sign, its aim is to attract a wider audience and to make the commercial activity thriving in the light of capitalist ideology. In order to fulfil this aim, the use of Italian does not suggest only the traditional and typical Italian food, it also affirms the authenticity of the kitchen through the stereotypical figure of the Italian cook, la nonna. This figure of la nonna, here a semiotic and written sign, can be interpreted as a brand for Italian culture and cooking regarding the definition of “branding” given by Sebba (2015): “process whereby a specific visual/graphical element of written language [such as an alphabetic character (see Screti 2018, 15)] becomes emblematic of a group of people”. In addition, Piller (2001, 170) observes that Italian is used in commercials “as the language of the good life, unambiguously connected to food”, which is considered as a “passion”. Moreover, the colour of the sign plays with a crucial ingredient of Italian food as it mirrors the colour of the tomato – figuring also on the sign and its title – that makes the sign generally visible in the entry of La Cité.

We then focussed on transgressive addition on a direction sign (that used to indicate the direction of touristic attractions) (Image 2), which does not fit within the capitalist construction of the space anymore as it has been heavily tagged and consequently acquires a dialogic nature. Indeed, the sign was originally regulatory, therefore representative of the mainstream ideology and has become almost unreadable under the tags. Direction signs’ primary purpose intends to help individuals to reach specific places, as touristic ones and implicitly, corresponds to a capitalist construction of the space. By covering the direction signs with tags – that are difficult to read and thus, to understand – the capitalist ideology is “challenged” by other discourses, called transgressive in opposition to regulatory, capitalist signs (Lefebvre 1991, 23).

Image 2 : Transgressive additions on a direction sign

The sign’s situation is crucial in order to fully grasp the power struggle underlying this direction sign and in La Cité in general. The sign is situated on the official boundary (also accepted by the locals according to our knowledge of the neighbourhood) of the neighbourhood where a great presence of graffiti characterize the margins of La Cité. In addition, the direction sign figures next to a tunnel that is completely tagged (see some parts of it on the left in the picture and also Image 8 in the appendix). This point illustrates the correlation between the boundaries as well as the margins of the neighbourhood and the expression of minority’s voices, considered to be transgressive as they do not fit in the main ideology and official signs. For instance, one of these voices mentions by code-switching a xenophobic concern in the tunnel as the Image 8 shows. Thus, boundaries of La Cité appear as a place “providing marginalised people a voice” (Mooney and Evans 2015, 101) as well as for transgressive discourses opposed to the capitalist ideology (see Image 9 in the appendix denouncing animal cruelty for its use of fur).

Image 8 : Graffiti in the tunnel ” Fuck les Valaisent [misspelling of inhabitants of other canton] + Portugais (Portuguese)” (Steph)

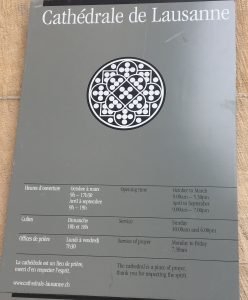

In this case, there are multiple signs displayed in the picture. The first one being analysed is the one present on the left corresponding to schedules of Le Musée historique de Lausanne (Image 3) (the historical museum). Similarly to other touristic places in La Cité, it is written in both French and English but no other languages (see Images 5 and 6 in the appendix). This multilingual practice contributes to the attraction of a wider audience in this neighbourhood, particularly as this museum is situated in front of the cathedral. It is contributing to the commercial activity of the museum and which can be related to capitalist ideologies as it represents a way to be lucrative.

Image 3 : Le Musée historique de Lausanne

On the right side of the picture, there are two different signs. One of which is solely in French and is the poster for the exhibition present in the museum that was also spread around the city. The other represents a promotion poster in Chinese. Although it is written in two different writing systems, traditional and simplified Chinese, the machine translation we used (Google Translate) translated the two lines as an indication of the availability of Chinese audio guide. It might suggest a frequency of Chinese speaking tourists and therefore, the museum’s advertisement is oriented to these specific consumers, so adapting its activity in relation to the multiculturalism we live in (Ben-Rafael et al. 2006, 9).

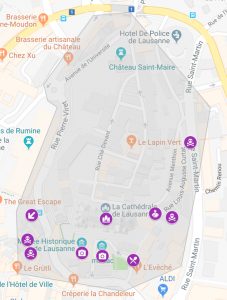

Image 4 : Direction signs leading to the cathedral

Finally, the last sign we are analysing is also an official, top-down one. Those direction signs (Image 4) are also present in the borders of La Cité, close to the tunnel and the transgressive sign (see Image 2 and appendix Image 8). However, those have not received transgressive dialogic additions. It can be linked both to the fact that it is situated in a busier street than the one near the tunnel. Another reason for its monologic nature is that it is situated high on the wall which can also protect the signs from graffiti.

These signs indicate the directions to access the main touristic attractions in La Cité. Those signs are mostly written in French. However, the sign indicating the direction of the cathedral on the left handside offers an alternative semiotic practice for a multilingual audience. It depicts the cathedral rather than have it translated in a different language. On the right of the picture, the highest sign indicates the cité cathédrale. Rather than translating it, a choice has been made to put an image. The use of illustration for directions applies to a wider audience. Illustrations allow a universal comprehension and avoid the need to present translations. A similar use of illustrations is also found in Image 7 (see appendix) where the rules and prohibited activities are represented with illustrations and act as a “structuration principle” in building the landscape (Ben-Rafael 2009, 45-6). It suggests an alternative way to describe the rules without having to translate it in different language and the need to choose which language to translate it in.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have intended to explore the cohabitation of two opposed discourses in the neighbourhood of La Cité, respectively a regulatory, top-down discourse and a bottom-up one, also qualified as transgressive. However, this cohabitation, as seen, does not necessarily imply harmony between discourses, mainly because of ideas conveyed within them that nourish a power struggle. Regulatory discourse is indeed vested in capitalist ideology and its shaping of space corresponds to and reinforces this mainstream influence, as observed in commercials and direction signs. On the contrary, transgressive signs acquire this designation as they do not fit in this ideology and tend to resist the capitalist conception of space by constructing their own, in our data by mainly using tags as form of expression.

The main limitation encountered in our paper is linked to the nature of a neighbourhood, namely its boundaries and margin zones. The delimitations of La Cité act also as delimitation for us in our research as we have to constrain to a specific space in which we have investigated the power struggle between top-down and bottom-up signs that actually might extend to a larger area.

Future research could focus on this specific neighbourhood during touristic periods, especially in summer and observe the measures, linguistic ones for instance, displayed in order to attract as well as to adapt their offers to tourists’ interests and on the other side, the bottom-up reaction to these measures. Another future direction might involve the soundscape of the same neighbourhood and to look at the existent languages and their representation in regulatory signs as well as in the bottom-up discourse, in other words an approach combining linguistic soundscape and landscape.

References

Ben-Rafael E., Shohamy E., Hasan A. M. and Trumper-Hecht N. 2006. Linguistic Landscape as Symbolic Construction of the Public Space: The Case of Israel. International Journal of Multilingualism 3:1, 7-30.

Ben-Rafael, E. 2009. A sociological approach to the study of linguistic landscapes. In Shohamy E. and Gorter D. (eds.) Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery. London: Routledge. 40–55.

Mooney, A., Evans, B. 2015. Language, Society and Power: An Introduction. Routledge. 4th edition. Chapter 5. 86-107.

Lefebvre, H. 1991. Plan of the Present Work, The Production of Space. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford : Blackwell. 1-67.

Papen, U. 2012. Commercial discourses, gentrification, and citizen’s protest: The linguistic landscape of Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin. Journal of Sociolinguistics 16/1. 56–80.

Piller, I. 2001. Identity Constructions in Multilingual Advertisements. Language in Society 30 (2). 153-186.

Screti, F. 2018. Re-writing Galicia: Spelling and the Construction of Social Space. Journal of Sociolinguistics 22/5. 516–544.

Sebba, M. 2015. Iconicity, attribution and branding in orthography. Written Language and Literacy 18: 208–227.

Trich S., Snajdr E. 2016. What the signs say: Gentrification and the disappearance of capitalism without distinction in Brooklyn. Journal of Sociolinguistics 21/1. 64-89.

Websites

Historical information on La Cité found on the official website of Lausanne tourism https://www.lausanne-tourisme.ch/en/Z5657/history, consulted on the 08.12.18.

Image 11, on the official website of the city of Lausanne: https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/presentation-des-quartiers.html, consulted on the 6.12.2018.

Statistic on La Cité, on the official site of the city of Lausanne on “population selon la nationalité” category: https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/tableaux-donnees.html, consulted on the 6.12.2018.

Appendix

Image 5 : MUDAC museum’s schedules

Image 6 : Cathedral’s schedules

Image 7 : Green spaces rules of Lausanne

Image 8 : Graffities in the tunnel ” Fuck les Valaisent [misspelling of inhabitants of other canton] + Portugais (Portuguese) (Steph)”

Image 9 : Transgressive sign “Sur cette promenade” [On this promenade], above the green space rules (see Image 7).

Zoom on the sticker denouncing animal cruelty

Image 10 : Anarchist graffiti that has been erased. However, it remains readable: “Abattre le capitalisme, construire la solidarité” [Bring down the capitalism, build solidarity) completed by the anarchist symbol.

Image 11 : Different quarters of Lausanne, the Centre under number 1. Map found on the official website of the city of Lausanne.