Authors: Lisa Wulf & Emma Pivoda

Abstract:

English branding is a well-known strategy in marketing and there are many researches on the usage of foreign languages in branding and its effects on the brand and consumers. However, as students on a campus, we were not aware of how much it was actually used. Therefore, we wanted to make our own research on the campus of the University of Lausanne and the EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) to know in which context and for which purpose English is used in branding. We collected the data for our paper by collecting bilingual English advertisements on both campuses. Through the analysis of these data we found that English was used mostly to give an image of internationality, which encompasses an image of modernity, urban, cosmopolitan and upper-class way of life, comprehensibility and in some sort, connects to quality, which however, was the least striking reason for English usage.

- Introduction

As students at the University of Lausanne, we encounter a lot of advertisements for different restaurants and events while we are on campus. To our greatest surprise, once we actually paid attention to it, most of it is brought to us with either a foreign brand name or foreign language catchphrase. Consequently, our interest was to know to what extent the English language in branding influences the consumers on a university campus and the purpose of English usage in the analysed ads. As a result, in this research, we want to analyse the purpose of foreign language branding, in this case English on a French-speaking campus, and its effect on the product and the consumers. Ayse Öztürk et al.(2015) found out that products with an English brand name are perceived as a more competent and that the consumer have more intention to buy if it is an English brand name. In addition to this study, Mrugank V. Thankor and Barney G. Pacheco also argue in their study (2015) that, in fact, attitudes and perceptions of consumers can be influenced by the brand name alone. Regarding these studies, we wanted to know how much foreign language branding is actually used and what kind of effect it creates. For this purpose we collected some commercials on the university campus of the University of Lausanne and the EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne). Our method was to collect these data on the most viewed billboards that are placed so that every student passing by sees them. Therefore, we hypothesize that English brand names or catch phrases are used in practically every advertisement and that it, in fact, promotes an image of modernity, urbanity, (Piller 2001) which will attract young university students, and that what is written in the local language has the purpose to give essential information.

- Theoretical framework

Ayse Öztürk et. Al. (2015) found that an “English brand name suggests a more competent product, more favourable attitude towards the brand name and higher intention to purchase the product” (283). To come to this conclusion they tested how business students perceive a brand name and its effect on the brand personality. They used three types of brand names: English brand name, English sounding brand name and a local brand name, which were used for two categories of products: blue jeans and café which were selected because they were categories that already often have foreign brand names. Mrugank V. Thankor and Barney G. Pacheco (1997) replicated earlier work done by Leclerc et al. (1994), which had investigated the effect of foreign branding on product perceptions and attitudes towards the brand name and see if their results were generalizable. Furthermore, Thankor and Pacheco also tried to extend Leclerc et al.’s study “by examining the role of gender as a moderating factor on the effectiveness of foreign branding” (17). They found that the results were very product specific and that there were no differences across brands and countries for their hedonic product. They also found that attitudes and perceptions of consumers can be influenced by the brand and especially that foreign branding can be important, which should encourage managers to, indeed, use these information to position their products and manipulate the image of their products. Furthermore, they find that the impact of Country-of-Origin (COO) is weak and therefore “suggest that country images are not readily transferred to products originating from those countries” (27). Additionally, there is also a significant interaction of gender with foreign branding that should not be neglected, which shows that foreign branding appears to have a negative effect on the perception of the product by females.

These researches are interesting to us because they prove how important foreign branding is for advertisement and proves that it has major effects on the consumer and the brand. We will use these studies and results as a basis and report them on a university campus where the local language is French and we will restrict the foreign branding on English branding, because it was, in our case, the most striking foreign language we saw on the campus of the University of Lausanne and the EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne).

- Contextualisation

We went on the campus of the University of Lausanne and EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) to collect our data, therefore our research context is higher education and concerns students. We chose this space because both of us are students and we never took the time to analyse and realize the constant multilingual advertisement around us. Nowadays, the University of Lausanne and EPFL are based next to each other in Dorigny. Furthermore, throughout the years, the Westside of Lausanne has been urbanised a lot: the first underground in Lausanne was innovated and the EPFL was built. The EPFL was founded in 1853, and at that time it was called “Ecole spéciale de Lausanne”. The building of the EPFL was a private initiative inspired by the Ecole Centrale de Paris. The name Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) emerged in 1969. It is also in this year, that the EPFL was moved to Ecublens-Dorigny. Because of these two renowned universities, a lot of students come from other countries to study there. The number of students and foreign students is growing every year. In autumn 2017 UNIL counted nearly 15’000 students[1] and EPFL nearly 11’000, with over 116 nationalities even though when they started they had less than 3’000 students.[2]

On the map[3] down below, we can clearly see that the two Universities are located next to each other.

- Methodology

To do our research and try to justify and support our hypothesis, we collected some advertising panels on the campus. We just walked around the campus, as we do every day, just focusing on advertisement. Throughout our data collection, and thanks to our focus on advertisements, we were astonished by the amount of advertisements in the first place, and furthermore, by the advertisement through foreign brand names and catchphrases, especially in English, even though the local language of this university is French and not English. First, we wanted to take a picture of every advertisement we saw, because we did not know what to expect by having a close look at the advertisement on the campus, but in the end, we thought that it would be better, for the purpose of this paper, to focus mainly on the English branding as it was the most prevalent and most used by the advertisers. The images selected for the final results were those which represented the most how English is used in advertisement on these university campus. Once we selected the right images that we found the most fitting for this research, we looked at the use of English language versus the use of French language, the local language of the region where this university is situated. As students ourselves in this university we are aware of the diversity that reigns there and the number of non-French speakers there is, but as Lausanne still is situated in a French-speaking region and its main language is thus still French, we had not expected to find that many English branding on the campus. We expected some, because we are used to advertisements and we see that it is often foreign language branding, but we had not expected that, on campuses of French-speaking universities there would be as many. Furthermore, we had to do some researches on the campus and on foreign branding to actually have reliable information for our research paper, which has taught us many new information on foreign branding and also on the universities’ culture and students. However, we found difficult to find the right information that were useful for our paper, which made it hard to find the main focus. Eventually, we thought that we should use our new knowledge on English and global foreign branding to look on the purpose of the use of English branding in the context of a University.

- Results

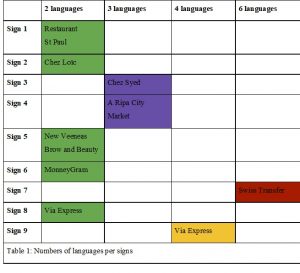

Table 1 shows the distribution of the purpose of the English branding used for each image in comparison with French usage. We explain in this table for which reasons the advertisers may have used English instead of French in some instances and, furthermore, also explain in which case and why French or English would be used (see Table 1 below). Consequently, we can see that the English language is used for several purposes as: attraction of the eye, international – famous – prestigious – stylish aspects, urban image, aspect of modernity and also for the purpose that everybody can understand what is sold.

Table 1 (see Appendix for a bigger format of the pictures):

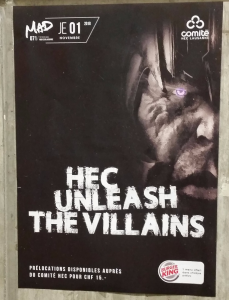

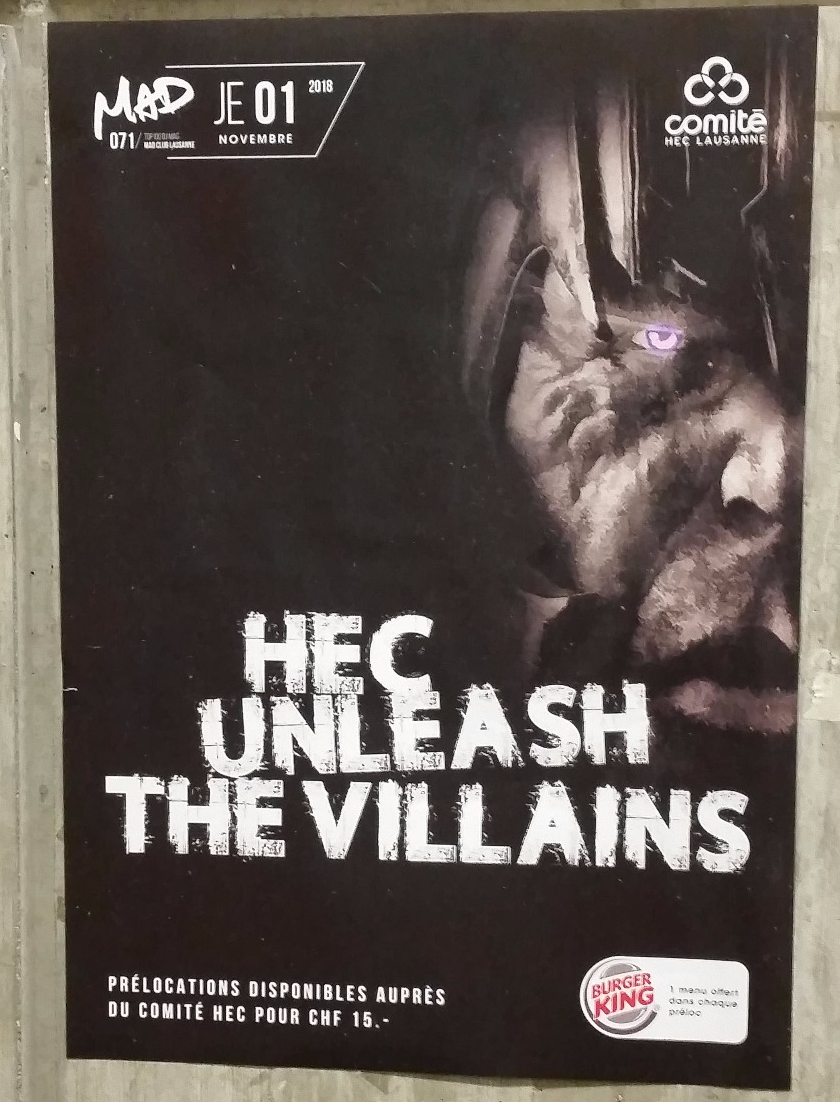

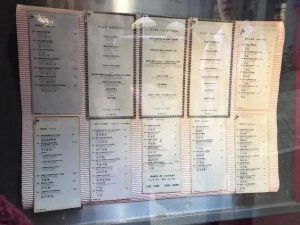

1) Picture 1: The French language is used for detailed and important information as opening hours, reductions, offers. However to catch people’s attention, they use the English because English becomes an important language of the society and here it makes it more serious and gives the image of internationality and modernity.

Picture 1: The French language is used for detailed and important information as opening hours, reductions, offers. However to catch people’s attention, they use the English because English becomes an important language of the society and here it makes it more serious and gives the image of internationality and modernity.

So here the English advertisement gives an image of modernity, urban, cosmopolitan and upper-class way of life and it is used as an eye catcher. English is used as a marker of internationality.

2)

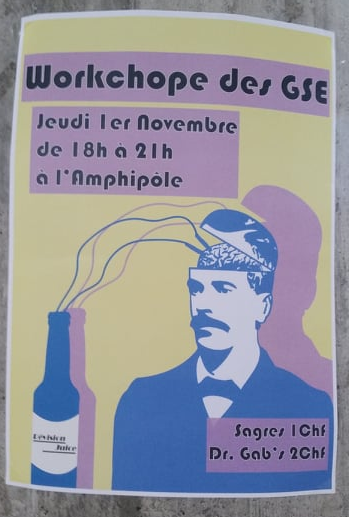

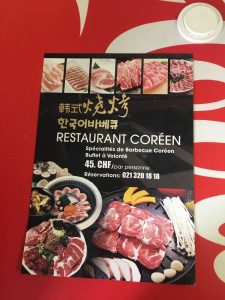

Picture 2: This beauty institute uses English for a catch phrase. Using English makes it sound more professional and mostly international which indicates a higher quality to the clients. Adding to this it also gives an image of urban, cosmopolitan and upper-class way of life.

Furthermore, the phone number, email address can be interpreted in both languages, and “free Wi-Fi”, which actually is in English, but nowadays has become so used that it is intelligible for everybody as “wi-fi” is an international word that is used in every language thus this instance only has the goal to communicate “free wi-fi”, which is intelligible by everybody.

So here English Branding is used to show, through the fact that it gives an international image of the brand, that it is better quality, modern and gives the image of urban, cosmopolitan and upper-class way of life.

3)

Pictures 3: The shop’s name is in English for the purpose to make it more attractive by giving the impression that it is international and therefore better because it shows that it gives an urban image, which attracts the people. The information are also in English because they use simple language to make people understand what the shop sells. However they use French for the opening hours because it is information that is needed to be understood and as it is located in a French environment, it should be in the local language so that it can still be identified with the region.

In this case, English branding is used to give the image of a international brand that is modern, urban, cosmopolitan and gives the image of upper-class way of life. Furthermore it is also used so that it is understandable by more people and to catch the eye.

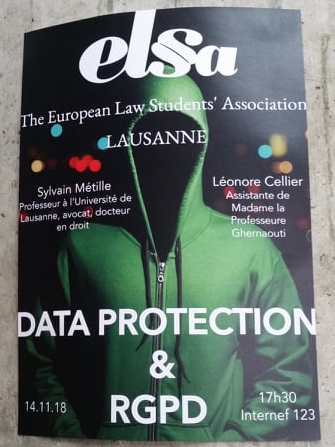

4)

Picture 4: Here the whole text is in English. There are only a few words and they are all words that are easy to understand for most people as they are easy vocabulary and “act” and “change” are nearly the same words in French. Furthermore, it makes it more international and shows that the purpose for what they are advertising is for everybody and everyone, no matter the language, is welcome.

In this case, the usage of English branding is there to show the internationality of the brand and to make it understandable for everyone.

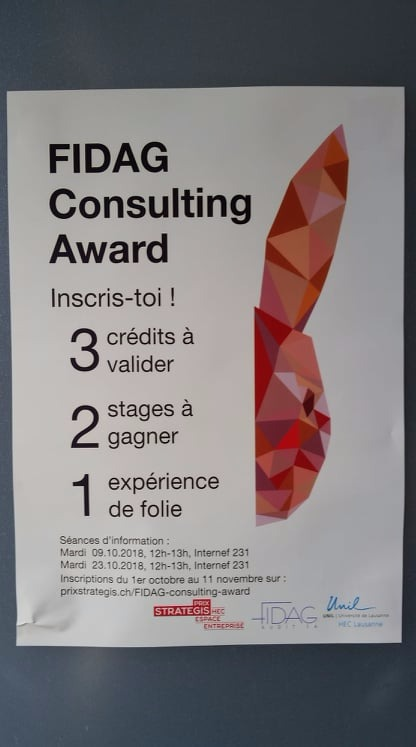

5)

Picture 5: Here only the title is in English because it attracts the eye and gives the impression that it is more famous/ international/prestigious. The rest of the information are in French because most of the population that sees this billboard speaks French and it is a cultural exhibition, which should be represented in the language to which it contributes to the culture, which is French in this case.

Thus in this case, English is used to show the internationality of the exhibition and furthermore to catch the eye of the person who passes by.

6)

Picture 6: Here only the title is in English because it is a well-known swiss show, which name is known thus is kept. The rest of the information are in French because most of the population that sees this billboard speaks

French and like picture 5 it is cultural. .

Consequently, in this advertisement it is mainly the fact that it gives the image that the show is international, thus “big and impressive”.

7) Picture 7: What here is written in French are information about the drugstore and what it offers. The English version is a perfect translation of what is written in French. The translation here shows that the drugstore concerns everybody and, as English is the lingua franca in this region it addresses everyone, and shows that the drugstore is well aware that a lot of students that come to there will not have French as their first language and thus the information should be intelligible for everyone.

Picture 7: What here is written in French are information about the drugstore and what it offers. The English version is a perfect translation of what is written in French. The translation here shows that the drugstore concerns everybody and, as English is the lingua franca in this region it addresses everyone, and shows that the drugstore is well aware that a lot of students that come to there will not have French as their first language and thus the information should be intelligible for everyone.

Here it is quite clear that English is mainly used to make it understandable for everyone what the drugstore is selling.

——————–

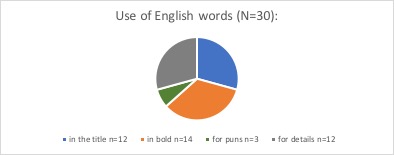

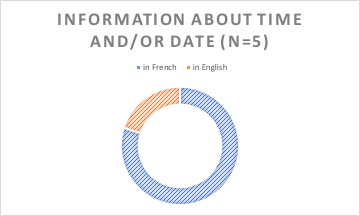

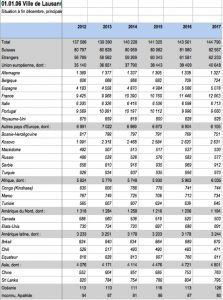

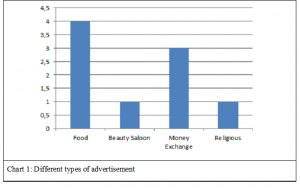

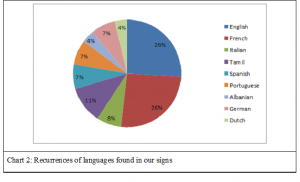

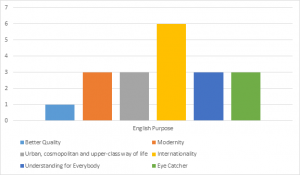

Regarding the distribution of the use of the English language in advertising, we wanted to see how it is actually distributed. For this purpose, we made Graph 1 (see below).

Graph 1:

(from left to right; Better quality/ Modernity/ Urban, cosmopolitan and upper-class way of life/ Internationality/ Understandable for everybody/ Eye catcher)

Graph 1 shows the distribution of the English use in branding by comparing all the different possibilities of use that we have decided on. In this graph we can see that internationality, thus the fact that in the universities there are students from around the world, is why advertisers use English as branding the most. It is the most striking aspect with the highest value. On the contrary, the lowest value is regarding quality. It does not seem as if the use of English is there to indicate better quality. However, regarding the other three categories we depicted namely urban, cosmopolitan and upper-class way of life, better understanding for everybody, modernity and eye-catcher, they all are on the same level.

- Discussion

By analysing our data, we have faced two different aspects of how English language is used on the campus. First of all, English is used for the purpose of the comprehensibility for everybody and secondly it is used for the purpose to make the product – billboard – restaurant – event more attractive to consumers by playing with English and French languages. Many students come from abroad and they do not necessarily speak French very well. Therefore, according to the first aspect of the English usage, some of the important information or billboards are written in English so that everyone is concerned as, for example, on the Polycare’s panel (picture 7). Polycare is a drugstore, thus, the information are written in French and also translated in English so that it addresses all people. Furthermore, as Sevgi Ayse Öztürk, Fatma Zeynep Özata and Feyza Aglargöz mention by citing Piller’s work from 2003 that “English is the most frequently used language in advertising messages in non-English-speaking countries. Internationally, it has become a general symbol of modernity, progress and globalization so it is used to associate a product with a social stereotype”. Indeed, English has become a very strong and important language in the world and we can, in fact, see in our data that this language is used a lot and mainly for giving an international aspect to brand through English advertisement. The English language is also used for the brand names to attract people’s eye and to give it a more important meaning because English is one of the strongest and international language in the world because of its characteristic of being the lingua franca in this region. Furthermore, as graph 1 shows, internationality seems to be the most used reason for English branding. In our opinion, this is due to the fact that the other reasons are all linked to internationality. Internationality encompasses the image of modernity, urban, cosmopolitan, thus having an exciting and glamorous characteristic associated with travel and a mixture of cultures, which results also in the idea of an upper-class way of life. Furthermore it is used for better understanding, eye catching and comprehensibility for everyone, because English has become the image of progress and additionally, is the Lingua Franca, which serves to communicate between people from all around the world. Consequently, we can see how it seemingly affect the consumers and which image it gives to them so that it attracts young people from around the world, reunited on a university campus in a French-speaking region.

- Conclusion

To conclude, we find out that the main purpose for using English language in a non-English-speaking environment for advertisement was internationality. Internationality is the main purpose but not the only one, as it encompasses many other aspects like modernity, urban, cosmopolitan and upper-class way of life, better understanding and, in also quality. These are all related to the fact that English is the language of globalisation because it has become a very important language that nearly everybody understands as it is the Lingua Franca in this context.

Unfortunately, we were limited for our research because we could not ask the actual managers of the shops and advertisements to explain why they preferred using English because we have not have had the right resources for this. Consequently, our results and explanation are mainly based on our understanding of the branding and what it provoked and appeared to be to us regarding the read literature and our understanding of it. Therefore, we do not know actually the true reasons why the advertisers thought that English is the better option to attract consumers. Therefore, actually speaking with the ones who were in charge of the advertisement could be a way to extent this research and get a better understanding of the purpose of English.

[1] https://www.unil.ch/central/home/menuinst/unil-en-bref/en-chiffres.html

[2] https://www.epfl.ch/about/overview/fr/presentation/chiffres-cles/

[3] https://www.google.com/maps/@46.5210304,6.5749249,15z

References:

Öztürk, S. A., & Özata, F. Z. (2015). HOW FOREIGN BRANDING AFFECT BRAND PERSONALITY AND PURCHASE INTENTION? (No. 2304200). International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences.

Thakor, M. V., & Pacheco, B. G. (1997). Foreign branding and its effects on product perceptions and attitudes: A replication and extension in a multicultural setting. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 5(1), 15-30.

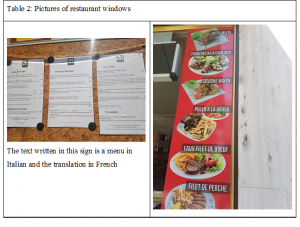

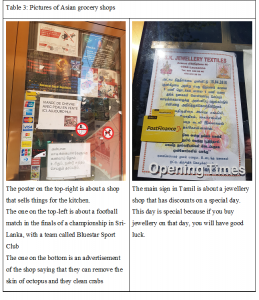

Appendix:

picture 1

picture 1

picture 2

picture 2

picture 3

picture 3

picture 4

picture 4

picture 5

picture 5

picture 6

picture 6

picture 7

picture 7