Multilingualism in ethnic businesses of downtown Lausanne

Abstract

This study focuses on the use of multilingual signs in ethnic businesses located in the center of Lausanne. To investigate the topic, we have selected three grocery shops in this area: S.M.T New Asian Shop, Uchitomi and Inside Africa. In each one of these shops, a different foreign language is visible and spoken. Lausanne is a French-speaking town where English is used as an international lingua franca, which makes it a city where at least two languages are used, and it corresponds to a form of multilingualism. Those specific shops, in which the owners speak many foreign languages in addition to the English lingua franca, are a valuable source for landscaping the use of foreign languages in the context of businesses. Moreover, these shops display multilingual signs that are also part of their own linguistic landscape. The comparison and analysis of the different uses of multilingualism in these shops constitute the base of our reflection. This investigation sheds a light in the use of multilingual signs in ethnic businesses as a way to reach the clientele from the same linguistic background and to attract the attention of any customer that might be interested in imported products.

- Introduction

The integration of migrants in a host country suggests several difficulties such as adapting in the new culture while keeping links with their own. One important aspect in this matter is the access to products from their place of origin. Indeed, having ethnic grocery shops owned by migrants allows their fellow countrymen to buy products that are not found in mainstream shops. It enables the local population to discover and access those products and additional services and information proposed in these places. The center of Lausanne, unlike certain other neighborhoods, is not associated with a specific kind or wave of migration since it is a cultural crossing area for most citizens of the Vaud as it is where the train station, the administration and most of the shops are. Therefore, we decided to concentrate our research on the use of migrant languages on commercial signs and advertisement in shops. The sample of shops we selected as our database are owned by people from different origins: S.M.T New Asian shop is a Sri Lankan business, Uchitomi is a Japanese shop and Inside Africa is Ghanean-owned shop.

To contrast our work, we compared our observations to three articles that also focus on the use of multilingualism in ethnic businesses. The first study by Guowen Shang and Shouhui Zhao (2017) investigates multilingual shops’ names in Singapore. The second one, by Bernardino Tavares (2018), studies the multiple functions of ethnic businesses. He explains that these shops often correspond to a cultural and social meeting place for whom. The third article, by Sabaté i Dalmau (2013), presents locutorios, which are shops in Catalonia that provide access to information and communication technologies and social help for migrants in addition to their primary function as shops.

In order to collect our data, we went to those grocery shops, took pictures of the apparent traces of multilingualism and discussed with the owners or the workers to get additional information about the shops and the use of languages there. Our essay will be divided in six sections following this one. We will first present the previous research on the topic and link them to our specific research question. Then, we will contextualize our research in the frame of today’s situation regarding immigration in Lausanne. Our methodology will then be presented in more detail as well as our results that will be discussed in a section devoted to this purpose. Finally, we will conclude our study by synthesizing our main findings.

- Theoretical framework

The topic of ethnic businesses has already been investigated in the field of multilingualism since they are places of cultural mixing. Guowen Shang and Shouhui Zhao (2017) focused on the choice of shop signs by grassroots individuals in order to manifest their personal inclinations regarding language use. This highlights the use of different languages in the multicultural society of Singapore (Shang & Zhao 2017: 8). Indeed, the owners of the shops usually choose names that reflect their own language and culture. The authors agreed that shop names signs can provide information about “language use patterns, language contact and linguistic creativity” (Shang & Zhao 2017: 8). Although Mandarin, Malay and Tamil are the three languages spoken by the ethnic groups in Singapore, English functions as a lingua franca and is used in different domains to make information accessible to all citizens. Even if English dominates the official sectors, one can observe a large diversity of languages in private shop signs. At first, the authors examined the distribution of English in shop names. They found out that over 96% of the stores have English names on their shop signs, 50.5% of these shop signs are bilingual and 2.2% multilingual. When choosing the language for the shop sign, the owner wants the information to be accessible to any client from the different ethnic groups. This shows a bottom-up multilingualism in the stores of Singapore in order to promote their business and culture.

A further relevant source for our research is a chapter from Bernardino Tavares’ thesis (2018). The author points out that Cape Verdean business places have different functions. On the one hand, they employ several family members and on the other, they endorse a social function that helps to keep transnational ties. Tavares presents the Epicerie Creole as an ethno-linguistic place. He underlines that this store is not only a place where customers can buy products but also find advertisements and information on posters and leaflets. The latter contains news about cultural events that take place in their community. Moreover, the atmosphere that can be found in the Epicerie Creole is meant to remind the clients of their homeland. The music and the odor diffused there refer to the culture of origin and seem familiar to the migrant customers. The fact that the employees of the shop are at least trilingual facilitates the communication with the customers.

The final piece of previous research we selected is Maria Sabaté i Dalmau’s article “Fighting Exclusion from the Margins: Locutorios as Sites of Social Agency and Resistance for Migrants” in which she presents the linguistic situation of migrants in Catalonia. Her research focuses on how the Spanish information and communication technologies (ICT) are made difficult to access for the poorest and undocumented migrants and also on how these migrants adapt to the situation through the use of locutorios as a bottom-up place of resistance, “alternative institutions for migrants” (Sabaté i Dalmau 2013: 249). Indeed, she explains that because of the particular linguistic landscape of Catalonia and because of the economic and political situation that does not easily welcome migrants, the ones who cannot afford ICT are marginalized by a top-down communicative system. Locutorios are shops developed by migrants that give the poorest access to ICT (e.g. computers, internet, phones) but also to social help (e.g. legal advice) and poor help (e.g. food distribution, showers). Those specific ethnic shops have adopted a central social role for those migrants as they are the most accessible network.

- Contextualisation

Lausanne is a multicultural city and the fourth biggest of Switzerland. It is a multicultural town with important migrations from diverse countries. According to an official website “La ville de Lausanne”, in 1979, Lausanne’s total population was 128,808 inhabitants. The percentage of foreigners at that time was 23.06%. In 2017, figures show that the population increased by about 16,000 inhabitants but the demographic structure has changed. Now, the percentage of foreigners has reached 42.98%. Therefore, one can see that the number of foreigners has almost doubled in 38 years.

City of Lausanne – Total population by region of the world and nationality, since 1979

Foreign population of Lausanne, by statistical subsector, 2015

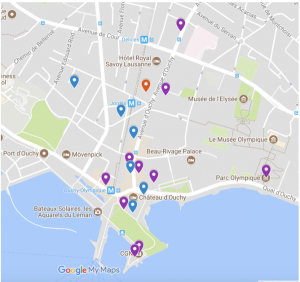

As mentioned earlier, we centered our study on the downtown area because it is where most intercultural encounters take place. Indeed, the map above demonstrates a concentration of foreign population in the center of the town, which is the area investigated. Regarding our ethnic businesses of African and Asian origin, it is relevant to mention that the African population in Lausanne has almost multiplied by six, and the Asian population by more than four (see the table above). This massive immigration can be explained by wars and political oppression in African and Asian countries. People come to Lausanne with the hope of a better life. These migrants create a new demand for foreign products that are imported and sold in ethnic business shops. Moreover, ethnic products are familiar also for the offspring of the migrants that have not lived in the foreign country but are used to them.

- Methodology

4.1 Data

The collection of the data for our research was done at two different times. First, we randomly walked in Lausanne, looking for grocery shops that had visible traces of multilingualism. We photographed the showcase and multilingual signs of those stores, but we lacked a specific angle of approach. In a second time, we returned to the stores to get additional information about how multilingualism is used on signs and advertisement there. We asked the workers and the owners the following questions:

- Where do you come from?

- In which language is the name of the store written and what does it mean?

- Are the signs written in the foreign languages a translation of what is written in French/English or is it additional information?

- What is the goal of writing part of the information in foreign language?

- How did you choose the name of your shops and what impact did you expect?

- Do the visible/featured languages have in influence on your customers? Which customers are targeted?

- In what languages do you communicate with the customers?

- Do you feel integrated in our town through exercising this activity?

Some of the shop workers refused to answer as they were busy or because they were distrustful to answer the questions, but the answers we did get helped us to narrow our focus. We decided to focus on the center of the town since it is where the biggest variety of multilingualism is found. We hesitated to choose one of the areas of the town that is associated with a certain immigration, but we thought it would be more interesting not to limit ourselves to a specific migration. We rather investigated how multilingualism is present in the most globalized area of the town and what the social functions of these shops are through multilingual signs.

4.2 Method

At first, we photographed ten shop windows of ethnic businesses in Lausanne. As we had not chosen a research topic, some pictures were not coherent, either because of their location (outside of Lausanne), or their monolingual signs. The second time, we interviewed the workers and their answers allowed us to narrow our reflection. We focused on three stores located in the center of Lausanne and took further pictures of their multilingual signs. We asked some specific questions to the store owners and workers about the languages on the shop windows and about their use of languages with customers. One difficulty we encountered was gaining the trust of store owners. At first, they were suspicious and thought we wanted to do an investigation on their shops. A further challenge was to understand the French or English pronunciation of our interlocutors.

- Results

S.M.T New Asia Shop

Located underneath the train station is the S.M.T. New Asia Shop that according to the owner, provides about 250 products from Sri Lanka, India, Africa and China. The store owners named the shop in English because it seems more international and targets a larger part of the population. Indeed, a large part of their customers are Tamils but there are also many people who traveled to East Asia who come to the store to find typical ingredients. The choice of English for the name of the shop can also echo the East Asian colonial past. Indeed, since a big part of Asia was part of the British Empire, English was adopted as a national language in many countries and it had an impact on the culture. It confirms that English is perceived as international. On the shop window, just below the name of the shop is written in a smaller typography “Produits et saveurs du monde” in French. The use of French attracts the attention of the French-speaking clients and make the practical information accessible. Furthermore, the owner explained that most clients address him in English and Hindi since his French is not fluent. On the entrance door, a sticker of a Hindu divinity saying “welcome” shows trace of the religious and cultural background of the shop owners. Just above, legal information is written in the official French language to be accessible to everyone and probably because of legal considerations as French is the official language and this might be a regulatory sign required by the municipality.

Uchitomi

The second store that is located in the pedestrian area of downtown Lausanne is “Uchitomi”, a Japanese grocery shop selling Japanese and Korean products. In the other shops, most of the signs are written in the Roman alphabet, but here we found transliteration, which is literal translation from one alphabet to another. The scripts written on the left part of the sign are in Chinese (Kanji), and on the right in Japanese (Hiragana). These are two scripts used in the Japanese language, one being easier for foreigners. They correspond to the French translation just below and stands for “sushi, Japanese food”. French is still the biggest and more visible script. The owner of the shop explained that “Uchitomi” stands for the surname of her father. When one transcripts this in Kanji, “Uchi” means “home” and “tomi” means “wealth”. She told us that she communicates in Japanese with their countrymen customers that are the largest part of their clientele, even if there are many French and English-speaking customers. The owner explained that, nowadays, many people are interested in the Japanese culture and that it has increased the proportion of non-Japanese customers that enter her shop. One can observe a difference in terms of prestige of the stores. Indeed, Uchitomi is tidier and elegant than S.M.T. New Asia Shop. Even though the two stores sell groceries, Uchitomi sells more sophisticated and expensive products (e.g. sushi), not only alimentation but also crockery. S.M.T New Asia Shop sells wholesale products (e.g. bag of rice of 20 kg) therefore, the overall atmosphere is different.

Inside Africa

Inside Africa is a grocery shop and a hairdresser located next to the main entrance of the train station. The word “Akwaaba” is written on the front door of the shop. A saleswoman explained that the owner of the shop is Ghanan and that in Akan, “Akwaaba” means “welcome”. Inside Africa invites locals to take an interest and discover their products, as well as targeting a specific community that will understand the meaning of “Akwaaba”. Moreover, on the front door, one can notice that the products and services offered by the store are written in French (Artisanat, Souvenirs, Coiffure…) for efficiency and for a wider audience who will probably have competences in the official language. The name of the shop is written in English since it is one of the official languages of Ghana as it was part of the British Commonwealth. Language reis connected to the colonial history of the country as in the example XX above. Communication with customers is mainly done in English and French.

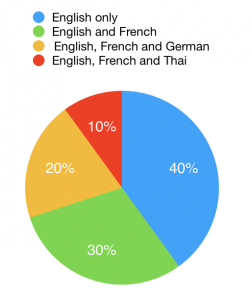

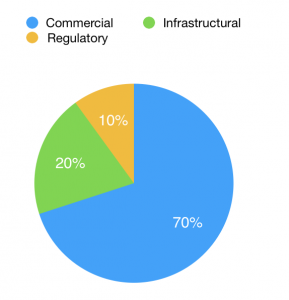

In order to summarize our observations, we made a quantitative analysis of the visible languages of the three ethnic businesses. Each square of the table shows how many times the languages are visible on the signs of the shop:

| S.M.T New Asia Shop | Uchitomi | Inside Africa |

| English 4x | Japanese 1x | English 1x |

| French 5x | Chinese 1x | Akan 1x |

| French 2x | French 6x |

This table demonstrates that French is the most commonly used language. This can be explained by the fact that we are in a French-speaking region and the information must be accessible to all the population. A parallel can be established with Shang & Zhao’s findings. Indeed, French is the privileged language in Lausanne, similarly to the way English is described to be used in Singapore (Shang & Zhao 2017: 13).

- Discussion

By examining different uses of multilingual signs in three ethnic businesses of downtown Lausanne and comparing different sources on the topic, we made observations and draw conclusions that were close to our expectations. Indeed, we found out that French and English are the most widely used languages. An important aspect we learned through those interviews is that no owner of those ethnic shops speaks only French. They all use foreign languages to communicate with their countrymen customers in addition to English, which is the international linga franca, and French which is the local official language.

In S.M.T. New Asia Shop, the use of English and French on the shop window is a good illustration of their use as lingua franca, similarly to the study of Shang and Zhao. The script “Phone card international” can be read vertically on the shop window, which means that the store offers supplementary services to allow its customers to call abroad and to keep transnational ties (Tavares 2018: 183). As described by Sabaté i Dalmau, these phone cards are an alternative bottom-up system that helps migrants to be integrated in the society and keep a link with their place of origin. In our context, the shops do not seem to have such an important integrative role as locutorios since the political and linguistic context is different. Still, one aspect that stays is the networking that takes place in those ethnic businesses. Indeed, poster and advertising in the grocery shops that are part of their linguistic landscape inform us about the multiple functions of this kind of space. If an owner accepts a poster, it means that it can interest a percentage of his customers. Similarly, ethnic grocery shops also have multiple functions since we can find information in other languages and community events which indexes their social function in addition to the commercial one. An example of this social function was found in S.M.T New Asian Shop, where a sign informed the costumers about a Chinese new year event accessible to those interested.

In Uchitomi, Japanese, Chinese and French are written on the signs. Posters of events related to Japanese culture and artists are exposed. It shows that these stores are also places where people targeted by the store’s culture come to inform themselves about events, activities and announcements that are offered in their community. This is also described by Tavares and Sabaté i Dalmau, when they talk about the cultural and social importance of these shops. The posters in Uchitomi are written in French to make the information accessible to all the customers even if they concern culturally marked events. Different kinds of activities are proposed such as a piano recital by a Japanese pianist, different Haiku workshops and a tour in the Japanese forest of the Arboretum. Another interesting proposal is to work in tandem in order to learn French or Japanese. This example illustrates the secondary functions of these multilingual shops.

Inside Africa confirms the thesis of Guowen Shang and Shouhui Zhao. In their study they assume that the use of English on shop name signs guarantees a large customer base from all language backgrounds. Inside Africa sells typically Ghanaian products that target the African customers of Lausanne (e.g. hair products for curly hair). These kinds of products do not really concern the local population who is not used to these products or simply does not know them. Standard products such as fruit and vegetables are mainly purchased by the local population. Inside the store, the African music made the atmosphere friendlier and recalled the culture of the country, as mentioned in Tavares’ research.

Overall, the foreign languages are always secondary since they cannot be understood by everyone and that the owners do not want to restrict their clientele. The role of using languages such as French, English, Akan, Chinese and Japanese is to put an emphasis on ethnicity and to attract the attention of the countrymen and also of the native people who want to discover exotic products or find products they tasted. It is nevertheless important to mention that, in the end, although foreign languages are used to display authenticity and attract people from a specific community, the importance of French as an official language or even English as a lingua franca is essential in ethnic businesses.

- Conclusion

To conclude, the results of this research show that these three ethnic businesses present a diverse multilingual landscape. S.M.T. New Asian Shop, Uchitomi and Inside Africa have different languages written on their signs, which could attract both migrant and native customers of Lausanne. The use of French and English as linguas francas shows that the information must be accessible to everybody, in order to not limit the clientele. The store owners specifically target a part of the population that shares the same culture as them but also the local population that would like to discover their products. In order to be able to continue their activity, they must target a wide and diversified audience.

Looking at the shop windows, we could see that French is the predominant language, which is suitable since they are located in a francophone town. The cultural practiced and events that are visibilised and promoted through these shops is also of great importance. Posters and advertisements of events regarding their community are visible on their shop windows. These ethno-linguistic places are an anchor point for the migrant population, who finds in these stores a repair for their community and share activities related to their culture. On the other hand, it also attracts native people who would like to discover these cultural practices.

However, this very own research is restrained by the number of shops we investigated and the fact that we only concentrated on one specific location. It would be interesting to further investigate other social factors such as the socio-economic level of the different shops and its consequences on the use of multilingualism on the signs. An interesting future step would be to ask oneself if the different use of multilingual signs informs us about the respective culture of each of these shops or about the social integration of their owners.

References

Guowen, S. & Shouhui, Z. (2017). Bottom-up multilingualism in Singapore: Code choice on shop sign. English Today 131, Vol. 33, No. 3., pp. 8-14.

Sabaté i Dalmau, M. (2013). Fighting Exclusion from the Margins: Locutorios as Sites of Social Agency and Resistance for Migrants. In A. Duchêne, M. G. Moyer, C. Roberts, Language, Migrations and Inequality: A Critical Sociolinguistic Perspective on Institution and Work. Multilingual Matters, Editors: A. Duchêne, M. G. Moyer, C. Roberts. pp. 248-267.

Tavares, B. (2018). Cape Verdean migration trajectories into Luxembourg: A multisited sociolinguistic investigation. Unpublished PhD thesis: Université de Luxembourg, pp. 181-198.

Appendix

https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/themes/01-population.html, (consulted 27/12/18).

Image 1 – Distribution / proportion of national languages in Switzerland: the yellow part represents the German speaking proportion, the blue part represents the French speaking proportion, the green part represents the Italian speaking proportion, and the red part represents the Romansch proportion.

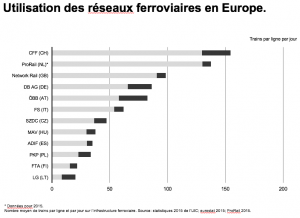

Image 1 – Distribution / proportion of national languages in Switzerland: the yellow part represents the German speaking proportion, the blue part represents the French speaking proportion, the green part represents the Italian speaking proportion, and the red part represents the Romansch proportion. Image 2 – Use of the railway networks in Europe according to the official main station of Switzerland’s statistics.

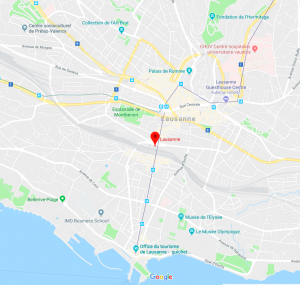

Image 2 – Use of the railway networks in Europe according to the official main station of Switzerland’s statistics. Image 2 – The location of the main station of Lausanne in the city.

Image 2 – The location of the main station of Lausanne in the city. Figure 1 – Front of the main station of Lausanne.

Figure 1 – Front of the main station of Lausanne. Figure 2 – Left front of the main station of Lausanne, next to the ‘Lausanne Capitale Olympique’ sign.

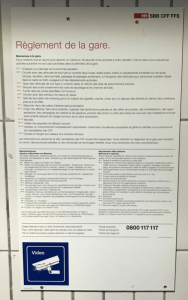

Figure 2 – Left front of the main station of Lausanne, next to the ‘Lausanne Capitale Olympique’ sign. Figure 3 – Custom service situated in the halls of the main station.

Figure 3 – Custom service situated in the halls of the main station. Figure 4 – Tickets machine of the main station.

Figure 4 – Tickets machine of the main station. Figure 5 – Infrastructural signs, indicating the opposite directions of the city and the lake.

Figure 5 – Infrastructural signs, indicating the opposite directions of the city and the lake. Figure 6 – Infrastructural sign indicating the destinations of the time in Germany and French.

Figure 6 – Infrastructural sign indicating the destinations of the time in Germany and French. Figure 7 – Shop situated at the front entrance of the main station

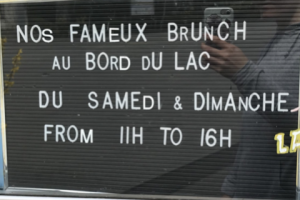

Figure 7 – Shop situated at the front entrance of the main station Figure 8 – Advertisement sign situated at the front entrance of the main station.

Figure 8 – Advertisement sign situated at the front entrance of the main station.