Multilingual Presence in Asian Food Places in Lausanne

Magdalena Camille Mena Pacheco, Dylan Ravussin

Introduction to Multilingualism in Society

June 2018

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the repartition of languages, namely official Swiss languages, English, and Asian languages in the context of Asian businesses in Lausanne. To do this linguistic landscaping, we visited Asian restaurants and markets to take pictures of the language signs we found in different sections of these businesses. We will try to illustrate the complexity of the relationships between these languages in those places. Indeed, although French is still often the primary language in the majority of Asian restaurants, probably in order to attract a broad customer base in these top-down institutions, the situation in Asian markets is different. English is often used as a lingua franca, but Asian languages are featured on many of the products’ labels, sometimes even exclusively, and French can thus lose its primary language status in some cases.

Introduction

The following research aims to examine the relationship between official languages in Switzerland (French, German, Italian), English, and Asian languages (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai) in Asian food places in Lausanne. The data was collected first-hand by visiting several Asian food places in Lausanne and Renens and capturing the linguistic environment through photographs taken of the visible exteriors of those businesses as well as the interior public signs of product labels and price labels throughout the inside of those places. The results found fit into a field not yet explored in the world of linguistic landscape studies. Previous research in similar fields has not yet been specific enough to Asian food places in Lausanne, nor has it been bold enough to be as straight-forward regarding the relationship between minority Asian languages and the many official languages of Switzerland.

The paper will be organized as follows: firstly, this research will address the previous research made in similar fields of study relevant to the history of multilingualism in Lausanne regarding the prevalence of English in multilingual communities and the use of Chinese in commercialized contexts. Secondly, we will present the context of our research: where the Asian food places are located, who purchases the goods, and what we learned about the customer base from speaking to the shop owners. Thirdly, we will touch upon our methodology and experience in gathering the data, and lastly, we will present our results and discuss their position amongst previous research in similar fields of study.

Theoretical framework

Because this research is quite specific, finding previous studies that were relevant to our topic became a challenging task. The main idea behind finding literature related to the topic is to allow further contextualisation of the results found. Some key ideas in the explanation of this research are: public signs, multilingualism, top-down vs bottom up production, primary vs secondary languages, landscapes, and commodification of language. Public signs are those that are visible to the public; in this paper, we categorized public signs as the labels of products inside of stores and restaurants or the exterior signs visible to pedestrian passerbys. Multilingualism is defined as the use of more than one language; in this case, how more than one language is presented in those public signs in a written way. Top-down vs bottom-up are terms that we use to categorize our findings regarding the dominant language presented in a multilingual setting; the top-down approach is typically more common in large cities (official languages given priority over minority languages) and the opposite (bottom-up) is what peaked our interests in the context of Asian food places. The primary language is the language that is given priority or that is more easily visible to the public eye. The secondary language is what is also present, but might be in smaller font or put to the side instead of front-and-center. The use of the word landscapes, for the purpose of this research, is used to describe a physical area as well as a socio-linguistic environment that affects the commercialized institutions within it. Finally, the commodification of language is the use of language in a commercialized setting, often contributing or in the favor of businesses.

The use of language, particularly in this case: the use of Chinese, contributes highly to the profitability of the businesses in the type of institution we chose, food places (restaurants and markets). “Culture is used both to frame public space and to legitimate the appropriation of that space by private and commercial interests,” (Zukin 1998). According to Leeman and Modan (2009), while the use of the Chinese language can be used to provide access to those who speak the minority language, it is also used as an opportunity for businesses to appeal to outsiders. A similar theme in the writings of Zukin and Leeman and Modan is that of the advantageous nature of the use of minority languages such as Chinese in commercialized contexts.

While the official language in Lausanne is French, the common lingua franca in and outside of those Asian food places which we studied was English. This is primarily due to the use of English as an international language, not only in Asia, but in a global sense. According to Garcia and Otheguy (1989), English as a global language has facilitated political and cultural understanding across societies. However, others, like Phillipson (1992) and Phan (2008) take on the view that English has characteristics of linguistic imperialism: presenting itself as a superior language, and resulting in various negative consequences. All in all, the “superiority” of English or the ease of the use as an international language contribute to its use as a lingua franca in Asian communities and across their commercialized world. In the case of Sayer (2010), the use of English in his research proved to be more than just due to its presence as a lingua franca, but also to convey some type of message by the use of English itself by making the product or service it’s advertising seem more “cool”, fashionable, advanced, or sophisticated. For the case of this research, the use of English was more likely used as a common language, as well as key words bolded in English to attract attention to potential buyers.

The previous research done in similar fields, unfortunately does not touch specifically on the use of official languages as well as English in Asian food places. Although this topic is quite specific, more research could be very useful, not only to benefit linguistic researchers, but also to benefit ethnic businesses in terms of what is most effective in public language use.

Contextualization

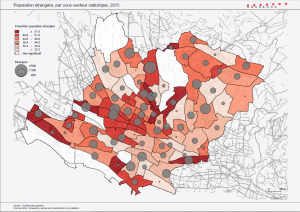

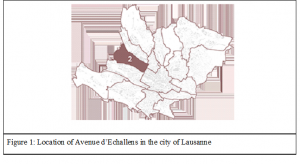

We chose to focus on Asian businesses in Lausanne because we thought that it would constitute both an interesting and broad enough topic. We were particularly curious about the dominant Asian languages in those businesses in a primarily French-speaking area of Europe, which is particularly interesting in a city that is largely made up of foreign nationals. Our original guess was that, with the progressive popularization of Asian culture in European society, we would have a considerable amount of places to choose from for our linguistic landscaping. A simple Google research proved us right: Asian businesses, especially markets and restaurants, are manifold in Lausanne. This could be explained by the aforementioned trend of Asian culture in Europe, but a more tangible reason is simply that Lausanne’s population is very diverse, especially compared with the other large Swiss cities. Indeed, it is amongst the four most cosmopolitan cities in Switzerland, along with Geneva, Lugano and Basel.

When looking into the demography of Lausanne, one can see that there is only one Asian nation (Sri Lanka) in the fifteen most common origins of the city’s inhabitants. This could lead to the assumption that the Asian customer base for the businesses we targeted was too limited. However, further investigation determined that Lausanne is home to people from over 160 countries around the world, so there is certainly a market for Asian businesses in town. Indeed, the interviews of two Asian shops owners led to the discovery that around half of their customer bases is made of Asians. Although we decided to limit our research to shops and restaurants, since they provided more than enough data for our paper, we did not set geographical boundaries for our landscaping. Asian businesses were selected from all over Lausanne and its surroundings, mainly because there is no “Asian neighbourhood” in the city, and the relevant locations for our study are thus spread out in the region.

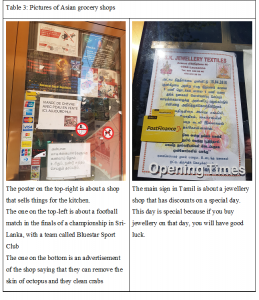

In the case of Fleurs d’Asie most of the products are imported mainly from Thailand, China, and Vietnam as well as other Asian countries, which are purchased by a customer base consisting of about half Asians and the other half non-Asians. Some of those customers are bilingual, speaking French and another native language. The products the owner chooses to sell are popular in Asia and could potentially appeal to other customers. The primarily way the owner displays the products are with descriptive labels, which allow store goers to decide which products they would like to purchase or what best suits their cooking needs.

In contrast with Asian Flowers, Thao, which is located in a more neighborhood type of setting, the customers are more local (non-foreigners) and live near the area. It’s more of a specialized items market, so there are some customers that go out of their way to find those products. The store is aimed to attract those that are curious to buy certain Asian products as well as those who are familiar with the products and cannot find them elsewhere, like in COOP or Migros.

Methodology

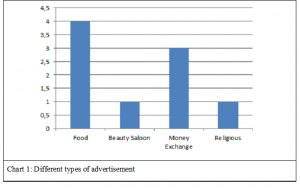

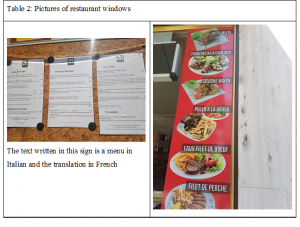

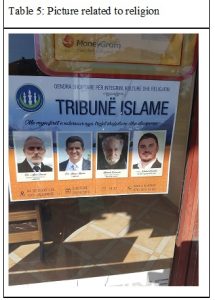

The data was collected from various locations around Lausanne and Renens. Outside signs, menus, window signs, and product labels were photographed with the intention of capturing the linguistic environment of the Asian food places in these cities. The outside signs, street menus, and window signs are all visible from the exterior of these businesses, while the product labels are visible mainly to shopping customers. The window signs included opening hours and the names of the establishments, as well as local advertising for events in their communities. The outside signs include the name of the business in a primary language and visible secondary languages. The menus were on display either in framed boxes on the exterior of businesses or displayed on easels. The product labels that were photographed were mainly general information on the packaging and some price labels on the shelves.

This project helped us understand a number of key aspects of the class, such as the notions of top-down and bottom-up, but it also brought us a lot of surprises. We expected to find a lot of restaurants with menus written in both French and an Asian language, which was not always the case, and we thought that a vast majority of the products commercialized in the stores would have French on their labels, which also turned out to be wrong in many cases.

Some unexpected difficulties were unveiled throughout the different steps of the research. The vast number of Asian businesses in Lausanne constituted both a blessing and a curse. After taking pictures of more than a dozen relevant places, we had to select which ones would provide the most interesting talking points for our paper. Also, while a lot of restaurants in Lausanne have an Asian name, a relatively significant amount of them are owned by people who do not speak any Asian language and only have French written on their doors and windows, which made them somewhat uninteresting for the purpose of this study.

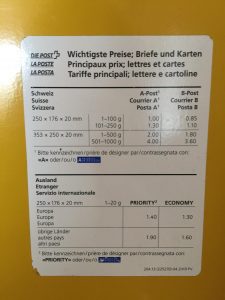

The exact opposite of this created another obstacle: the owners of some Asian shops are sometimes not very fluent in French or English. For example, the interview of the owner of Thao was made very difficult by the language barrier. Moreover, some products showcased in the stores were challenging to identify because English and French are sometimes only the third or fourth language featured on the labels of the products, if featured at all. Most of the labels were written in a vast array of languages, because they are often destined to be commercialized not only in Switzerland, but all over Europe. Finally, another unexpected language sometimes interfered with our work: German, which is more used in Switzerland than French, resulting in its presence on many labels.

Results

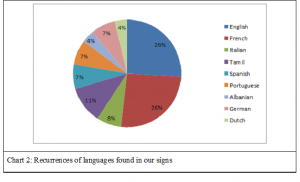

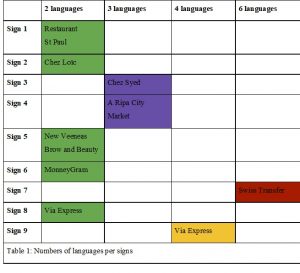

As seen by the table below, the results of our data collection are varied. Most of the institutions are categorized with a top-down production, meaning they showed the official language, French, priority over minority Asian languages. The most common secondary or second primary languages are English and Chinese. We found that the type of institution with the most secondary languages were the markets. They often displayed multiple minority languages on their product packaging labels as well as their price labels on their shelves.

In the case of Asian Flowers, we categorized the market as a bottom-up, because while the most visible language from the exterior is French, seen by the outside sign below, the interior of the shop consisted of labels in multiple languages, not only in French. They even sold products from Brazil, which had labels in Portuguese.

Overall, the markets tended to have a wider variety and representation of multilingualism due to their business-like nature. The presence of those various languages not only appeals to different Asian and English-speaking communities, but also allows for people from other communities to have access to authentic cultural experiences.

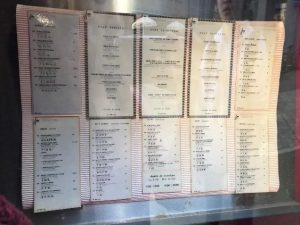

The types of communication that we recorded were primarily those regarding a message of description, not necessarily that of persuasion. The common theme that we found was that French was given a priority, especially with restaurants, as they would appeal to Lausanne locals going out to eat with their friends and family. Those restaurants that displayed a primary language other than French were seemingly foreign-owned businesses, attracting mainly people familiar with the food.

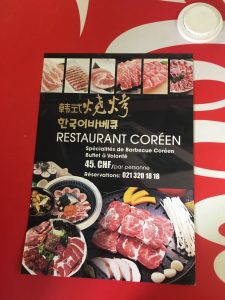

The English language displayed in signs was sometimes in the exterior signs, but primarily in the labeling of products in Asian markets. It was used as the lingua franca for many Asian products from various origin countries. Although the products did not originate in countries that use English as a primary or official language, some products had most of the front side of the packaging in English and multiple Asian or Swiss official languages on the back, like the Korean BBQ sauce product labeling. This was particularly interesting seeing that although English had no official reason to be on the packaging, it was being used as a common language over French, German, or Italian.

The Dragon restaurant is an Asian food restaurant that has an exterior sign, equally representing French, English, and Chinese, although it is a Chinese, Japanese, and Thai food restaurant. This finding is particularly interesting because it not only gives priority to official language (French), but it also gives priority to English (lingua franca) and Chinese, the more dominant Asian language.

Asian Flowers market: outside sign in French

Asian Flowers market: product labeling in Thai, English, and French

Asian Flowers market: product labeling in Portuguese

Asian Flowers market: product labeling in English and Korean

Dragon Restaurant: exterior sign in French, English, and Chinese

| Name | Institution Type | Primary Lang. | Secondary Lang. | Production |

| Mosaic | restaurant | English, French | top-down | |

| Takayama Sushi Bar | restaurant | French | English | top-down |

| Thao | market | French | Chinese, Thai, Vietnamese | bottom-up |

| Asian flowers | market | French | Vietnamese, Korean, Chinese, Thai, Portuguese | top-down |

| Dragon Restaurant | restaurant | French, English, Chinese | top-down | |

| Uchitomi | market | French, Japanese | top-down | |

| Chinatown | restaurant | French | Chinese | top-down |

| Ningbo | restaurant | Chinese | French | bottom-up |

| Asia Kim Dung | market | French | top-down | |

| Asian Shop, J. P. | market | French | top-down |

Discussion

The data found is enlightening to say the least. The relationship between official languages in Switzerland (French, German, Italian), English, and Asian languages (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai) in Asian food places in Lausanne is complicated and far from straight-forward. Many of the samples from the data show the the official language of French is given priority over other languages, in most of the cases. On the other hand, the lingua franca for many Asian food places, is English, especially for product labeling. No one conclusion can be made about the relationship between the languages in Asian food places particularly in Lausanne because of the diversity in culture, influence, and international nature of the city.

Because there is little research on related topics already existing, further research can be and should be made in the future in light of these findings. It would be very interesting to see if Asian food popularity has an influence on the multilingualism displayed in those businesses. Asian food is very popular in Lausanne and in the world in general, so it would be fascinating to see if there is truly a connection there.

A question that could not be answered in the time-constraint and capacity of this research paper is that of purpose. Based on the languages displayed, it would be a compelling research assignment to figure out who exactly the Asian food places are attempting to target as customers and if they are succeeding in doing so. The answer to that research would greatly benefit businesses in the Asian food industry and manufacturers for Asian food products alike.

Conclusion

Asian food places in Lausanne are primarily top-down institutions, giving priority to the official language of French over minority languages and the lingua franca. Because the relationship between languages and Asian food places in Lausanne is so complex, further research could provide clarification and clear conclusions on the subject. This particular research paper was very limited in its scope and time constraint. Had this project been longer and less limited, there might be some substantial conclusions made regarding the complex relationship between languages and commercialization in the communities of Lausanne. In brief, there are many factors regarding communication and language hierarchy that have contributed and will continue to contribute to the growing Asian food industry in Lausanne.

References

Deferred compensation. (2017) Portrait statistique 2017. Retrieved May 29 from https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/portrait-statistique.html

Garcia, Ofelia, and Ricardo Otheguy. “English across cultures, cultures across English.” A Reader in Cross-cultural Communication. Berlin, New York. Contributions to the Sociology of Language 53 (1989).

Le Ha, Phan. Teaching English as an international language: Identity, resistance and negotiation. Multilingual Matters, 2008.

Leeman, Jennifer, and Gabriella Modan. “Commodified language in Chinatown: A contextualized approach to linguistic landscape.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 13.3 (2009): 332-362.

Phillipson, Robert. “ELT: the native speaker’s burden?.” ELT journal 46.1 (1992): 12-18.

Sayer, Peter. “Using the linguistic landscape as a pedagogical resource.” ELT journal 64.2 (2009): 143-154.

Zukin, Sharon. 1998. Urban lifestyles: Diversity and standardization in spaces of consumption. Urban Studies 35: 825–839.