By Marina Trujic and Morgane Lopez

Abstract

This blog entry demonstrates the complexity of the question of languages’ hierarchy and the linguistic requirements that result from it in call centers. The globalization of English and the colonization of certain Asian countries brought different varieties of English, language varieties that are also due to the educational differences and to the different requirements expected between countries. It impacted the use of international languages in various commercial institutions such as call centers, which is included in the subject of this study. Considering these varieties of English, a hierarchy of language has been established in certain countries – for example Pakistan and India – and thus the companies introduce language policies: the referenced article approach “native-like” accent (i.e., GA standard) and pronunciation’s authenticity. Lasty, the English courses proposed and the linguistic expectations needed are presented as maximizing the job opportunities of the employees in call centers and thus provide better services for customers.

During the last decades, there has been both phenomenal industrial and technological progress worldwide. With this recent development came the need for societies to develop multilingual competences as a skill in the new service-based economy in order to trade with one another efficiently. This progress also brought an exponential increase in taxes and other costs for companies. Therefore, in order to maximize their profit, many companies relocated some of their services internationally. One particular service will be analyzed in this article: the example of call centers. Call centers are companies whose employees provide information or technical support and sell or advertise merchandise to its customers. Originally, call centers were based in the home country of the company they provide remote service for, but nowadays, most call centers have been relocated to countries offering tax reductions or other advantages for the companies. Because the average worker’s wage in Asian countries is much lower than the average worker’s wage in North American countries, a lot of north American companies have chosen to relocate their call centers to Asian countries in order to make more profit. When relocated, call centers are named outsourced call centers. Because employees provide services for English-speaking customers, English proficiency is required for employment. In this article, we will attempt to analyze why employers of international call centers feel the need for their employees to adapt their speech to be closer to the American standard in different Asian call centers in light of the globalization of English. In order to do so, we will first illustrate the notion of hierarchy of language and its social consequences. Drawing on previous studies, we will explain the different policies and decisions taken by companies in order to improve their employee’s English proficiency. We will then name the advantages such trainings and policies can bring to the employees. Finally, we will conclude this article by summarizing our findings and by answering the research question. We will offer future research directions as well as name the limitations of the reviewed studies.

English as the language of prestige in certain Asian countries: The hierarchy of languages

The first aspect that links linguistic performances to globalization is the hierarchy of languages established in certain Asian countries. This social hierarchy comes from the use of one particular language in some specific areas, for example English, as it is mainly used in political and economic contexts, along with other languages such as Hindi, Urdu and Malay. This linguistic hierarchy distinguishes four different aspects: the pride of English speakers, the indispensability of this language in the international workplaces – such as outsourced services and multi-nationals – as it is increasingly modernized, the pressure of the linguistic requirements inflicted by the leaders on their employees and the authenticity of English related to the individual identity of the employees. Concerning the authenticity of English, it is linked to the appreciation of the customers-staff relationship.

First of all, the ability of speaking a language like English provides social status because of the international statue it has, or in other words, thanks to “the power of internalized dominant discourses” (Duchêne 2008: 37). Also, while call centres are known to offer a salary “higher than that of many middle-staff positions in the government” to their employees (Friginal 2007: 337), certain countries (re)produce the hierarchy through education. For example, Pakistan has a “Pakistani English-using Elite” (Rahman 2009: 233), which would be associated to the expensive education of English and certainly to the distinction between elite schools and other Urdu-medium schools. Additionally, Pakistan workers:

“exhibit a lot of enthusiasm for their job, not only because they earn a higher salary than their peers, but also because they perceive themselves as being “smart”: They think they have acquired a native-speaker accent, which in their view, other users of English in Pakistan could not acquire.” (Rahman 2009: 238).

As a result, the good wage workers earn, the empowering status of English and this native-like accent are part of the pride that glows on people’s language proficiencies.

Secondarily, the hierarchy of languages also relies on what is needed in life in general. For example, the Philippines have a population that “aspire[s] to high-level proficiency in international communications in English due, for the most part, to the lure of overseas employment and, locally, of employment in multinational corporations such as call centres, export manufacturing, and technical assembly plants.” (Friginal 2007: 333). Known for their tradition of English-Filipin bilingual education, Filipinos give importance to linguistic abilities as it helps in their professional ambitions. Moreover, the English language, and more generally multilingualism, is perceived as a “practical necessity” (Duchêne 2008: 30). Whether in the professional field or in private life, linguistic performances and mainly English ones are indispensable assets.

Thirdly, if the hierarchical order of languages provides pride and professional assets, it also supplies pressure issues for the employees. Language policies, structured by several programs which we will discuss below, sometimes cause different practical “errors and misunderstandings” because of the inability of non-native speakers to talk about specific topics (Friginal 2007: 335). Also, in the case of India, being an employee of call centres has an ambivalent statue: “On the one hand they are the cool new generation, … on the other hand they are “cyber-coolies” who are “not in a real job”.” (Cowie 2007: 318). Moreover, the author precises that “Night shifts are regarded as so bad for health and social life that one will suffer “burnout” after a maximum of two years” (318). The pressure of work requirements impact employees in their mental and physical well-being, which will not help them acquire the linguistic skills required by their workplace. Also, since English is a language of prestige in Pakistan, the country “sets [English speakers] apart from other Pakistanis” because of their low-level proficiency in English (Rahman 2009: 246), which is also source of pressure for the ones that have to improve their language performances to integrate the elite society and to avoid situations where they are “called “weird”, “strange”, or “Pakistani” by their former colleagues or managers” because of their lack of English proficiency (Rahman 2009: 248). Furthermore, as “adapting to this level was seen as a challenge” (Lockwood 2013: 546), Indian experts finally termed “linguicism” “this inequality and hierarchy between languages and between speakers” (Sonntag 2008: 21). Consequently, we note that effective linguistic requirements of call centres provide pressure and stress for the employees, as well paid as they are.

Finally, the last aspect that shapes the hierarchy of languages, and thus the professional expectations of outsourced societies such as call centres, is the question of identity. Individual experiences with customers and the different issues that come from this linguistic hierarchy led to multiple consequences on one’s authenticity in work. Philippines defines the “native-like level” and its “prosodic patterns” as necessary, which significantly reduces the personal expression of the employee behind the phone (Friginal 2007: 339, 345). Also, a study on the Indian Call Centre industry states that “accent is treated as a skill to be acquired rather than a presentation of self” (Cowie 2007: 328), which seems to be the same in all of the Asian countries mentioned above. Lastly, Indian and Pakistani call centres use “Western pseudonyms” to “conceal identities”, which is perceived as “de-Indianizing” by certain American journalists (Rahman 2009: 237; Sonntag 2008: 9).

Forced to talk in English? Language policies in call centers

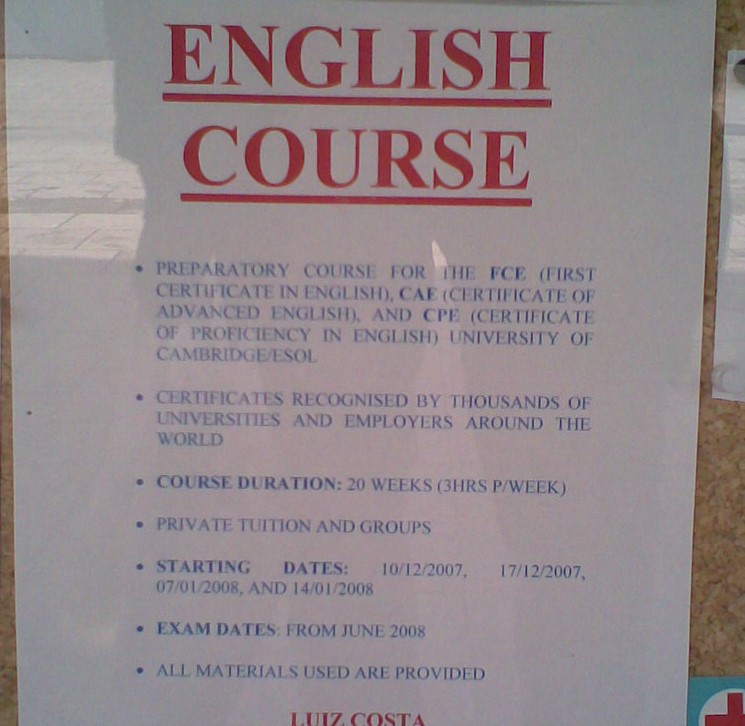

Talking about the hierarchy of languages is very important because it is directly linked to the policies and training put in place in the Asian companies themselves. As seen in the previous paragraphs, the cleavage between the varieties of spoken English – for those who can speak it – in Asian countries is due partially to their social and economic backgrounds, referred to as a “gap in English education” (Friginal 2007: 333) among speakers. This is why the hierarchy of languages greatly impacts outsourced call centers, since many call centers express the wish for their employees to appear and to sound as if they were native English speakers, in their communication skills, meaning their vocabulary, accent and intelligibility, and in their knowledge of idioms and jokes, meaning their “cultural understanding” (Friginal 2007: 340). These appear to be crucial knowledge requirements in order to be trusted by the customer and to sell products or to be able to properly assist customers without there being any misunderstandings. The assistance an employee should be able to provide require GA English fluency, as employees have to be able to “handl[e] call-in queries and technical support; [correspond via] e-mail [and] online chat, travel and [provide] consumer services; and [handle] medical and legal transcriptions” (Friginal 2007: 331). With the wish of improving one’s English came the need for English proficiency trainings or “English language communications training” (Lockwood 2013: 537), which are realized either by private teachers, such as personal “trainers hired by the larger call centers themselves” (Rahman 2009: 240), or by organizations dedicated to training new employees, the so called “call center academies” (Friginal 2007: 333). These training have the goal to either try and meet the linguistic requirements for call center employees, i.e. speaking a General American English, or to improve the skills of long-term employees needing only English for intelligibility purposes, such as “support engineers working at [an] India site” (Lockwood 2013: 537). An example of the reasons why these academies became popular is the case of Filipinos, for whom “fluency, accent reduction and the acquisition of high-level English” (Friginal 2007: 334) are important. Indeed, having employees speaking in a GA English profits the companies hiring them, since it allows them to be more influential, as well as for the workers, since these skills allow them access to well-paid jobs. It is very interesting to note that whereas English fluency is important in call centers, some companies in India providing technical support admitted to disregarding “the level of English language competency at the interview” (Lockwood 2013: 537). The goal of English proficiency trainings lies not only in improving the employees’ English, but also in reducing their accent and speak in a subjective “neutral accent” (Rahman 2009: 238). These courses last two weeks or fifty hours in some places (Rahman 2009: 239), even if improving an accent can take years. The main subjects are “Customer Care, Culture, Attitude, English, and Phonetics” (Lockwood 2013: 548). However, even with the implementation of such courses, many call center employees reportedly do not meet the official requirements “in the customer service setting” (Friginal 2007: 339), which impacts the quality of their work.

Shaping the employees’ future by improving their language proficiency

A last aspect that will be analyzed in this article is the opportunities language proficiency of GA English can bring in Asian countries for individuals. As stated before, language hierarchy plays a huge part in their life-trajectories and opportunities of speakers. It is the basis of most international companies (for example call centers) as it is of popular beliefs and knowledge that employees speaking a variety of English close to the Standard form will have more success in their jobs and sells than those speaking a different variety. The main reason for this is that “inability to adjust to the needs and demands of the caller could mean a failure of the transaction, with significant negative effect on business” (Friginal 2007: 335). This inability could have serious consequences for the workers, as inefficiency leads sometimes even to the “termination” (Friginal 2007: 335) of workers. Because of that, language proficiency in the American standard English can be and is often regarded as a positive advantage, both for future job opportunities it brings and in order to remain employed. Not only are trainings beneficial to the employees for selling purposes, but Filipinos employees “appear […] to fully embrace th[e] company culture in English use, and demonstrate […] enthusiasm in attending additional training.” (Friginal 2007: 340). Even though Rahman’s study proves that even if call center employees perceive their jobs, the different policies and training to improve their English, as positive, they view them as an opportunity to study abroad or travel and not in order to work in call centers indefinitely.

Final thoughts: Future directions and limitations

In conclusion, we saw that the hierarchy of languages has different consequences, positive and negative ones: while speaking a high-level English proficiency gives social status to the employees and improves the life quality they lead, it also causes pressure about the communication skills required and inevitably questions the individual identity of workers. Once we considered the effective linguistic adaptations – i.e. requirement to adopt a GA accent and variety, often through training – asked by Call Centres, the reasons why these international companies adjust their requirements are implied by the impact of these changes on the customers’ opinions. The two main discourses that arise from our literature review are the improvement of the quality of commercial exchanges, which consist of less misunderstandings and errors linked to the English performances of employees, and the strengthened reputation of outsourced call centres that are made accessible from everywhere as well as trustable by everyone thanks to the use of an international language such as English. Primarily translated into the use of a “neutral” accent, national adaptations of Asian countries seem to be linked to the will to inhibit language variations. As a limitation, we effectively cannot unravel the initial necessity of these linguistic policies; are these requirements simply needed by the globalization of English or are them established to conceal individual identities in order to satisfy all customers? Also, we have not specifically analysed the linguistic abilities of employees by giving explicit examples of what is expected of them, we just developed what is being put in place by private companies to improve their level of English, which is another limitation. Finally, as future direction, we could analyse other types of Asian communication agencies, such as selling websites or more generally online assistance, could be interesting to compare to call centre policies.

Key Words: Globalization of English, Call Centres, Asia, Outsourcing, Accent, Neutralization, Identity and International Communication.

Bibliography

Cowie, C. 2007. The accents of outsourcing: the meanings of “neutral” in the Indian call center industry. World Englishes vol. 26. no. 3, 316-330.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2007.00511.x

Duchêne, A. 2008. Marketing, management and performance: multilingualism as commodity in a tourism call centre. Language Policy vol. 8. no. 1, 27-50.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10993-008-9115-6

Friginal, E. 2007. Outsourced call centers and English in the Philippines. World Englishes vol. 26. no. 3, 331–345.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2007.00512.x

Lockwood, J. 2013. International communication in a technology services call centre in India. World Englishes vol. 32. no. 4, 536–550.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/weng.12060

Rahman, T. 2009. Language Ideology, Identity and the Commodification of Language in the Call Centers of Pakistan. Language in Society vol. 38. no. 2, 233-258.

Sonntag, S. K. 2008. Linguistic globalization and the call center industry: Imperialism, hegemony or cosmopolitanism?. Language Policy vol. 8. no. 1, 5-25.