By Ludovick Flachat and Asia Thommen

Short description: In this blog entry, we investigate the reasons behind and the locations in which the swiss advertisement industry employs English as a lingua franca.

Keywords: Multilingualism, Advertisement, Switzerland, English, Lingua Franca.

Introduction

Multilingualism is one of the most typical characteristics of Switzerland. According to Patricia Ronan (2016), since 1938, there are four national official languages in the country: German, French, Italian and Romansh. Although its linguistic variety is one of Switzerland’s key characteristic, it remains one of the main issues within the country. Indeed, managing these languages is not an easy task even if the territoriality principle is in place, making each canton responsible for the designation of an official language. Therefore, out of the 26 cantons, 17 have German as their official language, 4 have designated French only and 1 opted for Italian. There are also 3 German and French bilingual cantons (Bern, Valais and Fribourg) and 1 German, Italian and Romansh trilingual canton (Graubünden).

Nevertheless, it is still hard for every Swiss resident to understand and be understood everywhere in the federation. Furthermore, it raises the question of which language(s) to teach the younger generations. Consequently, English as a lingua franca is used as an answer to fill the gaps. Its use in Switzerland kept on increasing from post-World War II onwards, becoming the main language of 4.4% of the Swiss population (Ronan, 2016: 16). English as a lingua franca is especially used in work environments such as the army, universities or advertising. The language is thus considered as neither a second nor a foreign language, but its status lies somewhere in between (Cheshire, 1994). Hence, it is expected that English is also used in Swiss advertisements.

In this blog entry, we will investigate the use of English in Swiss advertising based on academic papers and Swiss ads that we collected on the internet (Autumn 2020). We will apply the theories in the literature to our country’s advertising system, exploring why Swiss-based companies use English for its advertising and in what ways it is doing so. In particular, we will study phenomena such as “language contact” which consists of the interaction of two or more languages found in the same material, leading to a transfer of linguistic features and style.

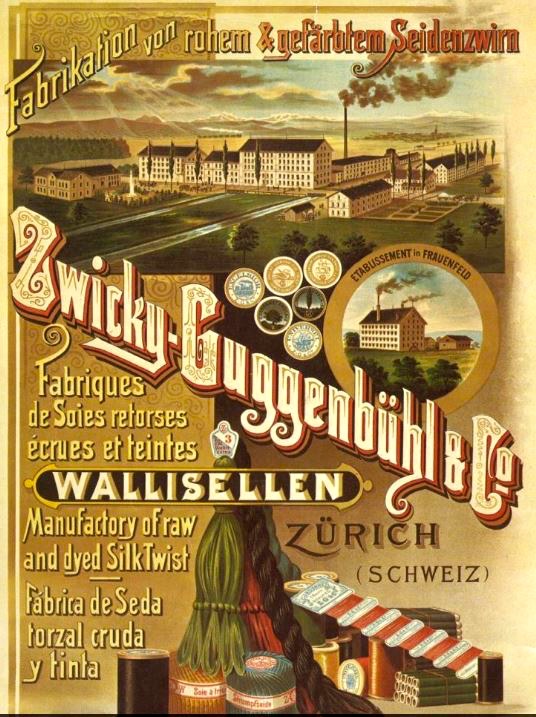

The one above is an obvious case of language contact in Switzerland. We chose this example of advertisement because it illustrates perfectly the complexity induced by the Swiss’ spectrum of languages. The manufactory is based in Zurich, in the Swiss German part of Switzerland, which explains why the main title is in German. However, it is translated in three other languages. One of them is French, another official idiom of Switzerland. The other two are Spanish and English, two of the most spoken languages in the world. This choice was probably made in order to expand the audience of the advertisement to a more international level.

The first part of the blog entry will provide some theoretical context in order to explain why English is part of Swiss society and therefore the advertising system. In the following section we will highlight how the language is used in Swiss advertisement and the fundamental reasons for the choice of English in the Swiss advertisement system by also giving some examples. Finally, we will conclude our blog entry by illustrating the limitations and the possible further directions for research.

Theoretical Framework

The advertising world is in a continual expansion, becoming more influential and thus receiving an increasing budget. This development hence induces a modification of its codes and values such as the birth of “super brands” (Piller 2003: 176) in the 1990s. Super brands are trademarks that take their value from their symbolic charge created by the ways in which they are advertised more than the product itself or the service they provide. Brands such as Nike or Calvin Klein play with these codes and the “conceptual value-added”. The value added is the additional feature or economic value which a company adds to their product before offering it to the customers. In order to make their brand successful internationally thanks to globalization, advertisers have created a “brand pidgin” (Piller, 2003: 176) which consists of logos and the use of slogans. These tools lead to a global understanding and recognition of one’s brand.

Interestingly, one way of doing so is by language contact, which increases the use of English in non-English-speaking countries. Moreover, English is globally considered as the language of modernization and technology (Piller, 2003: 175). Its spread is facilitated by the extensive use of the language in global communications (80% of the total), but also by the internet marketing. Switzerland is also affected by this phenomenon in many ways, including the use of English as a marketing strategy. In fact, the Swiss population, being multilingual, often uses English as a foreign language. This implies that Switzerland is a part of Kachru’s “expanding circles”. Kachru’s model defines three different categories of users of English (Bhatia, 2012: 571). First, the “inner circle” (UK, USA etc.) which is composed of the countries that have English as L1 and created the norms which then spread to the other circles. The second is the “outer circle” (Singapore, India etc.) thus the circle of people who learned English as a second language because of their background as an English colony. At last, the “expanding circle”, which consists of most English speakers worldwide, in which English does not have a governmental status but is generally studied as a foreign language. It is a circle which is dependent on the norms created by the Inner circle. Most of swiss speakers learn English as a foreign language which makes them a part of the last group.

As we have seen before, multilingualism in Switzerland is its strength in terms of tourism trade and international relations, but also a debate within the country. Though it is true that in Switzerland, English could be seen as a foreign language, it is also often used to fill the lack of knowledge of the other official languages, thus accepting the role of an internal lingua franca. Cheshire even defines it as a “‘neutral’ second language for all the Swiss language groups” (1994: 453). English can thus be considered as a lingua franca that can be the bridge between all parts of Switzerland without favouring one of the four official languages.

Previous studies and examples

In her research, Ingrid Piller discusses the use of English in advertising, comparing it to the use of other foreign languages. Usually, the use of an additional language, different from the national language, is related to ethno-cultural stereotypes as it is the case of English within British class in continental Europe. However, as Piller underlines, in the case of English, focusing on the ethno-cultural stereotypes is irrelevant considering its overuse in many areas. Thereby, English is more associated with social stereotypes such as prestige, modernity or progress. As we can see in the next few examples, the use of English in advertising is happening alongside the three Swiss official languages (German, French and Italian). In our blog we decided not to include an example of the Romansh-English contact as the language is dying and finding a multilingual advertisement would be too difficult.

As this first example highlights, English is used to emphasize the prestige of this Swiss luxurious watch. This is a Swiss ad on the Rolex’s website. The website chosen is mainly in French, but as you can see the marketing team decided to name the product with an English name: “sky-dweller”. English product naming is the most favourite and easily accessible process in multilingual advertising (Bhatia, 2012: 579). Additionally, it often happens that a product’s name and advertisement are an expression of the company’s origins. For instance, Coca Cola is an American brand which has decided to keep their slogan “taste the feeling” in English in all countries including Switzerland. Bhatia (2012: 580) also explains that English can occur in many structural domains such as slogan and product name but also company name or logo, labelling and packaging, pricing, main body, headers and sub headers.

Accessed on: 12/12/2020.

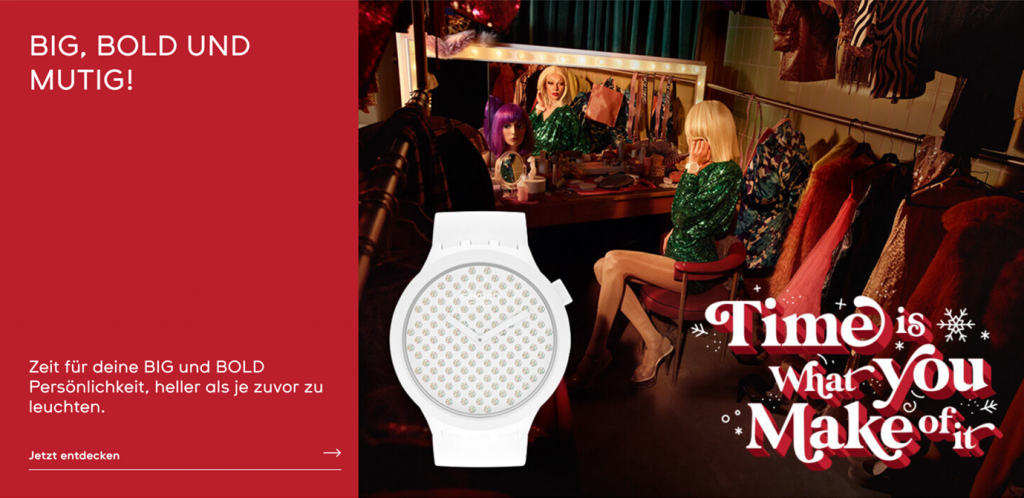

In this second example above (see Figure 3), we can see an ad from the Swiss company “Swatch”, which sells watches and bracelets. Here the advertisement on their website is in German but uses English to name their product (BIG BOLD) but also for their slogan: “Time is what you make of it”. The website is also available in French, where the slogan still includes English. English slogans usually are sentence-like and not just one-word structures and the Swatch’s ad is a perfect example. As for the example of the Rolex watch, this is another case of English product naming, considered as the simplest process in multilingual advertising (Bhatia, 2012: 579).

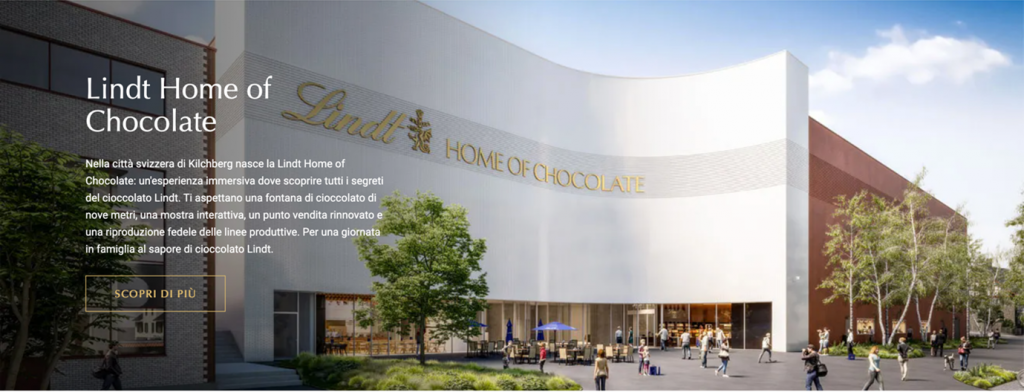

In this third example we can see that the description of the website, thus the main body, is in Italian, but the header is in English. This is probably done in order to reach a wider audience, and to suggest to the reader that the page can be translated to other languages. Moreover, as in the Rolex watch advertisement, English could be used to emphasize the luxury and modernity of the brand. As for the last examples, English is thus used to exalt the level of internationality and modernity of the product in order to attract the receiver of the advertisement to buy the Swiss product.

The three given examples are from swiss brands on their swiss websites in the three official languages. It is interesting to notice that this phenomenon appears in all of the three official languages of Switzerland. Indeed, one language could be more likely to use English. For instance, we suppose that a minority language such as Italian could perhaps increase the use of English in the publicity world or even in the canton altogether, in order to make sure that the advertisements and information are understandable by all Swiss visitors. Ultimately, all parts of Switzerland use English in their marketing strategies.

As we saw with these examples, English is an extensively used language within Switzerland, and it does not seem like it is only used to show a level of internationality which could attract tourists, but also for other interesting reasons. In 1994, Jenny Cheshire wrote an interesting paper in which she talks about advertisements in Switzerland. The year of this article could be seen as a complication, but we consider that her conclusions are still relevant for the case of Swiss advertisement nowadays.

Firstly, she states that the use of English in Swiss ads could be seen as a convenience for the advertiser who can use the same commercial in the four different linguistic regions without having to change its text. Secondly, Cheshire develops an intriguing point on how the Swiss use English as “a way of transcending a problematic national identity, in order to allow them (the Swiss) to construct a self-image that is consistent with the favourable image that they present to tourists” (Cheshire, 467). Swiss advertisers thus use(d) English in their ads in order to connect with international tourists and construct a more favourable image of the land for travellers coming from all over the world. Finally, a more practical point must be considered. Switzerland has a total number of four national languages and at least eight different German-speaking dialects (varieties of Schwytzerdüsch). Therefore, we could say that there is not one single language that could serve as a national symbol of the Swiss identity. Furthermore, three of the four official languages are also the languages of the neighbouring countries, an aspect which diminishes the concept of Swiss national language.

What we still consider as a controversy is whether, from a more ethical point of view, it is in Switzerland’s best interests to use a foreign language and not one of its own national languages. Maybe using more multilingual advertisement in the four official languages would encourage Swiss residents to learn or at least remember some of the other Swiss languages. In fact, Swiss pupils have to learn a second national language at an early stage of life. This reveals the importance for the swiss residents to learn other national languages, in order to have broader work and educational opportunities. Nevertheless, a study led by the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education[1] revealed that only twelve of the twenty-six Swiss cantons learn a second national language before learning English. The fourteen remaining cantons provide an English education before the second national language. What is interesting to notice is that the fourteen cantons in which English is taught before a second national language are mainly the Swiss-German cantons: Uri, Obwalden, Nidwalden, Lucerne, Zug, Schwyz, Glarus, St. Gallen, Aargau, Appenzell Innerrhoden, Zurich, Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Thurgau and Schaffhausen. In fact, the matter of language education is a regional decision. But the fact that for the Swiss German region it is more important to learn English very early in the education implies that English is used more than in the Swiss French or Swiss Italian region. This hypothesis is confirmed by a study lead by the federal office of statistics (De Flaugergues, 2016), in which it is established that generally the English language is used more in the Swiss German regions than in the other Swiss regions.

Conclusion

The case of Switzerland is thus very interesting in terms of multilingualism. It already has four national languages of its own, but as we can see from the examples of advertising above, English is often used as a solution to reach the most extensive audience possible. It must be kept in mind that it is the federation of Switzerland which is multilingual, not the population. This means that not all of the Swiss residents are able to communicate in a national language, i.e. without using a lingua franca to understand each other (which in most cases is English). The issue of communication can also be found in the context of advertisement, a reason why English might be so extensively used in the world of publicity. As said before, another reason for using English is because it is considered as the language of modernization and technology (Piller, 2003: 175), characteristics which can help the selling of a product. Finally, as Cheshire (1994) states, the reasons which lead Switzerland to use English in the advertising system are multiple and can be summarized in three main points. The convenience for the advertiser who does not have to translate the announcement for different linguistic regions, the creation of an alternative and tourist-friendly identity and finally a more practical point, the fact that Switzerland cannot be represented by a single language. Considering all of these issues we personally find that the use of English in Swiss advertisement can be considered comprehensible. Because of the multilingual peculiarity of Switzerland, English provides a fundamental contribution to the comprehension of advertisements and we perceive the use of the language as a necessity.

According to what we have learned with this research we would find it interesting to consider the case of English in more official matters as in the communication from the Swiss government. This would allow us to comprehend the importance and the policies used while managing English as a lingua franca in a country which is already multilingual.

Definition of concepts

Foreign languages: language which is not indigenous and used as a vernacular in a given country.

Lingua franca: language used in order to communicate between two individuals which do not share the same native language.

Monolingual: when the language repertoire of an individual or an entity is composed of only one language

Multilingualism: when the language repertoire of an individual or an entity is composed of more than one language.

Multilingual advertisement: advertisement which uses more than one language.

Official language(s): usually the language (or languages) used by the government, hence the language(s) which has a legal status in a particular country/territory.

References

Bhatia, T. K., and W.C. Ritchie. 2012. Bilingualism and Multilingualism in the Global Media and Advertising. In T. K. Bhatia and W. C. Ritchie (ed.), The Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism. Blackwell Publishing, 563–597.

Cheshire, J. 1994. English as a Cultural Symbol: English as a Cultural Symbol: The Case of Advertisement in French-Speaking Switzerland. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 15.6, 450-469.

De Flaugergues, A. 2016. Pratiche linguistiche in Svizzera : Primi risultati dell’Indagine sulla lingua, la religione e la cultura 2014. Statistica della Svizzera. Available at: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/it/home/statistiche/cataloghi-banche-dati.assetdetail.1000181.html. Accessed on: 22.12.2020

Demont-Heinrich, C. 2005. Language and National Identity in the Era of Globalization: The Case of English in Switzerland. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 29.1, 66–84.

Piller, I. 2001. Identity constructions in multilingual advertising. Language in Society, 30.2, 153–186.

Piller, I. 2003. Advertising in a Site of Language Contact. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 23, 170-183.

Ronan, P. 2016. Perspectives on English in Switzerland. Cahiers de l‘ILSL 48, 9-26.

Vettorel, P. and V. Franceschi. 2019. English and other languages in Italian advertising. World Englishes, 38.3, 417‑434.

Images:

Figure 1: Arnold Zwicky’s blog. 2021. A Swiss thread. Arnold Zwicky, twenty-fourth of January. Available at: https://arnoldzwicky.org/2018/06/19/a-swiss-thread/. Accessed on: 24/01/2021.

Figure 2: Rolex. 2020. Home page Sky-Dweller Presentation. Rolex, Twelfth of December. Available at: https://www.rolex.com/fr. Accessed on: 12/12/2020.

Figure 3: Swatch. 2020. Swatch Home Page Big Bold Presentation. Swatch, Twelfth of December. Available at: https://www.swatch.com/de-ch/homepage?gclid=CjwKCAiAlNf-BRB_EiwA2osbxdP87GBAl87WGj8TH_GlEaHooryf04dHxpjepQDJdZNDM-bDLlqTKRoCCTIQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds. Accessed on: 12/12/2020.

Figure 4: Lindt. 2020. Home page Lindt. Swatch, Thirteenth of December. Available at: https://www.lindt.it/. Accessed on: 13/12/2020.