Marine Fiora, Katharina Schwarck

Content

In this blog post, we will investigate multilingual education in the plurilingual country of Switzerland, what its policies and programmes are, and how and why they are implemented.

Keywords: bilingual education, Switzerland, territoriality, monolingual ideology, multilingualism

Figure 1: Ⓒ Ben White

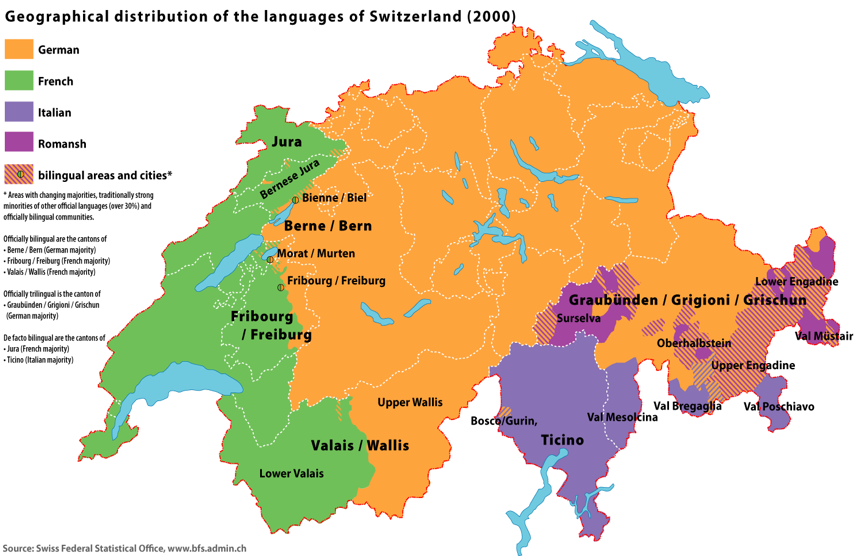

Switzerland is officially a quadrilingual country (Meune 2010) where the national languages are German, French, Italian and Romansh although many other minority languages are spoken as is the case with English, which is becoming increasingly important. Since Switzerland is a federation, the sovereign cantons define their official language (Paternostro 2016; Zimmermann 2019), according to the main language spoken by their inhabitants: this is called the principle of territoriality. It is customary to have only one official language in each different region. Switzerland is therefore, rather than a quadrilingual country, a mosaic of monolingual regions where the principle of territoriality creates a well-defined separation between the languages (Grin and Schwob 2002). The language borders are visible in the Figure 2 illustrates. However, the majority of Swiss people are far from quadrilingual. The notion of language borders is important for the understanding of the topic of multilingual education because it highlights the difference between societal bilingualism and personal bilingualism. Indeed, a country can be bilingual while the citizens are not necessarily (Grin and Schwob 2002). Of the 26 Swiss cantons, only three are officially bilingual (i.e. Valais/Wallis, Fribourg/Freiburg, Berne/Bern) and only one is trilingual (i.e. Graubünden/Grigioni/Grischun) (Grin and Schwob 2002). In order to improve understanding between language areas, it is obligatory for children to be taught a second national language at school. It is necessary to understand the language policies and their implementation in different cantons in order to maintain national cohesion in the country.

Figure 2: “Map Languages CH” © Marco Zanoli. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Multilingualism is a language ability which includes the use of several languages in our repertoires. However, in our current neo-liberal period, this faculty can be a great asset, whether cultural or economic. Having multiple language repertoires gives access to prestige languages and facilitates communication between people with different mother tongues. Moreover, with English becoming even more important and global throughout the years, learning it as foreign language has become increasingly common and almost required in order to use it as a lingua franca.

One way of learning a foreign language is bilingual education. As García (2009) explains, bilingual education is a mode of education in which the language studied is used as a means of communication and not as the target of study as is the case in traditional language classes. The aim of this approach is to immerse students in a different culture, language and way of thinking, enabling them to obtain intercultural skills. This method is called immersion teaching and has been practised all over the world since the 1960s to varying degrees. According to Lys and Gieruc (2005), the first study experiment of this type of teaching was conducted in bilingual Canada, where parents of English-speaking students had demanded a more effective type of French teaching, in order to improve their children’s socio-economic chances. Following this demand, an experimental programme was set up to verify the effectiveness of this type of learning. During these first immersion experiences, parents were concerned that learning another language could have cognitive repercussions on their children. The results of this evaluation were very positive and led Canadian political authorities to promote this type of teaching throughout the country. Shortly after Canada, many other countries moved to develop education in foreign languages, as for instance countries in Europe. This type of language teaching seems to be becoming more widespread in order to develop students’ socio-economic chances and intercultural communication (Lys and Gieruc 2005). Another way of learning a foreign language is Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) which allows the learning of a language in non-linguistic focused courses. This means that some classes will be taught in the target language without being a grammar or vocabulary course. When not all classes are taught in the target language, but also in the pupils’ regional language, this structure is also called a dual immersion programme.

These modes of learning can be particularly useful and interesting in a multilingual country like Switzerland, where federalism allows Swiss cantons to choose their school curricula and how they approach language learning (Grin and Schwob 2002). In fact, Switzerland has always worked with the goal to promote the cohesion of its cantons. From the 1970s onwards, the study of a second national language in primary school was added to the study of the pupils’ native language (Paternostro, 2016). This raises the question of the implementation of bi/multilingual education in public schools in the Swiss cantons and the differences between them.

The Swiss Federation has been accepting several kinds of bilingual school courses since 1995 (Elmiger 2008), allowing the cantons to build up their own programme and promoting exchanges between the different language areas (Meune 2010). One notices that in regions of contact between two languages, bilingual programmes develop more naturally, and there are more possibilities for educating children which take into account their particular language situation when they are, for example, speakers of a national minority language. Evidently, measures and programmes are not restricted to native speakers of a national language, but do also extend to students’ whose parents’ might be migrants and whose home language might not be official Swiss. In officially monolingual regions the creation of a bilingual programme depends on the school and it aims to improve students’ skills and socio-economic chances (Elmiger 2008). Nevertheless, not all cantons have regulations on the design of bilingual courses in the secondary level, especially in smaller cantons or in those where only one or a few schools offer a bilingual curriculum. Where these programmes do exist, they are not always equally detailed.

In 2008, the cantons of Geneva and Zurich – the biggest and most international cantons – Berne/Bern and Fribourg/Freiburg, and monolingual Aargau and Vaud had developed detailed specifications for their bilingual programmes, often in order to promote them (Elmiger 2008). Typically, bilingual programmes exist sporadically in German-speaking Switzerland while in Vaud’s gymnases (the Swiss equivalent of High School), in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, such programmes are available to everybody in state schools. The bilingual programmes usually last three or four years and begin in the ninth or tenth year (ages 14 to 16) in the German-speaking part and in the tenth or eleventh year (15 to 17) in the French-speaking part (Elmiger 2008). Most programmes are based on high school students (ages 15 to 19) taking part in classes in the immersion language at their home school and a host school, where the target language is spoken (at least 600 classes in total for the whole programme). In other schools the immersion only takes place in a host school of the target language. According to Elmiger (2008), in 2008, about 10% of all Gymnasium/gymnase students in Switzerland completed a bilingual school course, 40% of all Gymnasien/gymnases offered bilingual education, and the number has not stopped growing since. The most frequently taught immersive subjects are History and Mathematics although the range of subjects found in the individual programmes is very broad (Elmiger 2008). The most immersive teaching takes place during the penultimate or the last year before the Matura or maturité. The total number of bilingual lessons varies: while some schools seem to teach fewer than the 600 periods prescribed by the canton, others even exceed the target substantially as some schools plan up to 1400 immersion lessons (Elmiger 2008). Since Switzerland’s cantons are sovereign regarding school policies, the decision regarding bilingual education is different in each of them.

To illustrate this, the French-speakers in Berne/Bern are a minority and are traditionally present in the Jura bernois. Meune (2010) shows a major distinction in this canton compared to the others. Indeed, the Bernese Constitution precisely associates either German or French with a given district based on territoriality. In the exceptional case of Bienne/Biel, every inhabitant can choose their own administrative language as well as the main language taught at school.

Meune (2010) highlights that in the city of Fribourg, the two languages are co-official but that it is very complicated to have a perfect balance between them at all levels. Fribourg is a French speaking town with a minority of German speakers who are entitled to administrative services and schooling in German. Moreover, the canton of Fribourg/Freiburg offers bilingual courses in its university and in several of its schools of tertiary education. The University of Fribourg, for instance, is fully bilingual and allows students to take courses in Fribourg as well as at the monolingual universities of Neuchâtel (Francophone) and Bern (Germanophone), allowing all curricula to be bilingual. The Fribourg School of education, for its part, provides administration and teaching in both German and French and encourages second language immersion for students, with the idea that all future teachers should have bilingual skills.

Figure 3: Sign at Fribourg/Freiburg Train Station “Quelque chose a changé, en notre…” © centvues. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Valais/Wallis was the first canton to declare itself bilingual, but it offers a much clearer linguistic separation than Berne/Bern and Fribourg/Freiburg (Meune 2010). In their study, Grin and Schwob (2002) compared two Valaisan/Walliser CLIL programmes: one which began in kindergarten and another that began in third grade. In both examples, part of the classes were given in the target language by a native speaker. The programmes have shown that pupils in their fourth year of primary school who have followed the bilingual path from kindergarten onwards had almost the same understanding in the target language as native speakers (10-20 percentage points less). They also highlight that bilingual education does not only give better results from the students but also much more enthusiasm towards foreign language acquisition (20% more satisfaction). The canton also offers the opportunity for each municipality to create a bilingual structure under certain conditions (Canton du Valais 2006). At Gymnasium/gymnase level – called collège and Kollegium respectively in Valais/Wallis – the canton offers bilingual German-French education in the Kollegium/collège of Brig and Sion, a bilingual English-French education in the collège of Saint-Maurice and a German-English education in the Kollegium of Brig. In this way, we can also observe an emergence of the importance of English, both in the German and on the French-speaking part. Furthermore, the school of education has two sites, one francophone, one germanophone. There, students start their studies in their native language but over the course of their diploma need to spend at least two semesters immersed in the other language on the other site (Brohy 2008).

Ticino is the only Italian-speaking canton in Switzerland. This canton has the particularity of making the learning of two other national languages at school as well as English compulsory. Since a change of policy where the students can choose the languages which they want to learn and French passes from compulsory to optional in upper secondary, we notice a decrease in the learning of French (-12% less students) (Paternostro, 2016). This can be explained by the prevalence of German in Switzerland. Indeed, many people in Ticino believe that German must be acquired in order to have a secure future (Zimmermann 2019).

The trilingual canton of Graubünden/Grigioni/Grischun – in which inhabitants speak German, Italian, and Romansh – highly promotes the two minority languages, Italian and Romansh, in order to keep them alive. Therefore, Italian- or Romansh-speaking students are encouraged in their use of their native language at school and the presence of these languages in schools is reinforced. The canton also offers courses partly in the students’ native languages, partly in a second national language, as well as it offers immersive phases for both.

In the year 2000, the monolingual canton of Vaud introduced le modèle mixte – the mixed model – of their maturité bilingue. This consists not only in a first year of schooling in a regular class, with pre-registration for a maturité bilingue but also in a period of language exchange in a German-speaking region. During this period, the students follow the classes of a host gymnase for either 10 to 12 weeks at the end of their first year, or for the entirety of their second year. Then the student is required to be part of a bilingual class in the second or third year, where subjects such as Mathematics and History are taught in German, if possible. Students also attend regular German classes. Following the introduction of this programme, various financial and organisational support measures were taken to help students and families. The greatest problem, however, was finding instructors who have the right qualification to teach a subject in German. (Lys and Gieruc 2005)

In Elmiger’s (2008) survey, the schools were asked why they offer a bilingual Matura course and the most important reason for bilingual high school education was parent or student demand, which is particularly high in bilingual cities, but also in German- and French-speaking Switzerland. The second important point was the opportunity for the school to distinguish itself through a bilingual education programme. This second reason is much more visible in the Gymnasien in German-speaking Switzerland while in the gymnases in French-speaking Switzerland this is far less the case (Elmiger 2008).

Thus, bi- and multilingual education is more widespread at secondary levels (Elmiger 2006) even though there are also bilingual curricula at kindergarten and primary school level, which are more common in private schools (Grin and Schwob 2002); in primary schools, some subjects are taught in the target language (Elmiger 2006). However, schools often depend on the availability of suitable teachers. Counterintuitively, bilingual cities present a great shortage in suitable teaching staff. Elmiger (2008) presumes that this reflects the strict cantonal requirements for teachers in order to allow the highest quality of teaching. Indeed, the teachers must have a university degree in the target language or equivalent (Grin and Schwob, 2002).

Meune (2010) examined the individual bilingualism of the officially bilingual cantons and found the following percentages: 39.2% of the French-speaking inhabitants of Fribourg/Freiburg consider themselves bilingual compared to 72.9% of the German-speaking citizens. In the canton of Bern, this percentage is similar in proportions: 58.8% of German-speakers are bilingual compared to 52.1% of French-speakers. The bilingual canton with the lowest percentage of bilingualism is the canton of Valais/Wallis: 21% for French-speakers and 42.6% for German-speakers. This low percentage among the Valaisans/Walliser can be explained by a much clearer language boundary. In fact, the famous Röstigraben divides the canton into two very distinct parts and the semi-cantons function as juxtaposing parts (Meune 2010).

This blog investigates the provision of bilingual education in Switzerland by comparing the demographic differences between the cantons and their school curricula. It can therefore be asserted that Switzerland, although multilingual, has a monolingual ideology (Zimmermann 2019; Zimmermann and Häfliger 2019). The majority of regions have one official language and the majority of Swiss speakers are fluent in only one national language. Cantons are sovereign regarding their education policies, supporting their creation of school curricula according to their needs. Nevertheless, cantons’ sovereignty also implies that some can make less effort to make the population multilingual. Globally, bilingual education has a growing demand, as parents and pupils believe it to grow one’s socio-economic chances. The schools also use it to differentiate themselves and the biggest impediment to bilingual classes is teachers’ availability. Most bilingual education in Switzerland consists of an immersion period in a different linguistic territory and content courses in the target language in the home school at Gymnasium/gymnase. However, universities as well as other schools at a tertiary level offer bilingual curricula, either through agreements with other universities, or exchange programmes with other associated sites, especially for teacher trainees. The results of bilingual education are outstanding: not only do the pupils achieve better academic outcomes, but they also manifest more enthusiasm for education overall.

Can Switzerland be considered as a model for multilingual education? Switzerland has the difficulty of needing to handle several languages while also having to ensure that linguistic minorities speaking a national or a migrant language are represented. Furthermore, the principle of territoriality can be both a disadvantage, because it does not allow language mixing easily, and a strength, as it gives way to cantonal freedom to shape schooling according to the population’s needs and differences. If education policies were federal and “one-size-fits-all”, the schooling system would suit the people concerned far less. Therefore, we believe that Swiss education is always adapting itself to the community’s needs, which can be considered as the most important factor when looking for a model for multilingual education. We therefore believe that the growing demand of bilingual education in Switzerland shows the importance of acquiring a second language in the eyes of the population. Many of the current programmes are optional but promoted. Despite their optional nature, their popularity is continually increasing among students. Although secondary and tertiary school programmes seem to be successful, one could implement even more bi-/multilingual programmes at a young age, especially in bilingual regions, in order to facilitate language acquisition and allow earlier interaction between different speakers. Moreover, it is important to mention the rise in popularity of English. English was taken up as a subject in schools because parents and students saw the need for English economically. Schools quickly adopted the learning of English into their curricula (Stotz 2006). Some German-speaking cantons, such as Zurich, have even decided to teach English to children from the first year of primary school (ages 6 to 7). English is thus taught before French. Therefore, Stotz (2006) wonders how Swiss education will look like in a few years: with more and more students requiring English before any national language, national languages might soon not be considered worth learning anymore.

A limitation of this paper is that most of the extensive data on this subject is over a decade old and offers only a glimpse into the current situation. We assume that many policies and programmes have changed and grown and that more and more schools have adopted the approach of a multilingual education. In addition, the place of English as a potential lingua franca may also have evolved and be more significant than described. It could therefore be interesting to investigate the learning of English to the detriment of the national languages and its increasing presence in Switzerland.

References:

Brohy, C. 2008. “Und dann fliesst es wie ein Fluss…“: l’enseignement bilingue au niveau tertiaire en Suisse. Synergies: pays germanophones. 1, 51-66.

Elmiger, D. 2006. Deux langues à l’école primaire: un défi pour l’école romande, avec la collaboration de Marie-Nicole Bossart. Neuchâtel: Institut de recherche et de documentation pédagogique.

Elmiger, D. 2008. Die zweisprachige Maturität in der Schweiz: die variantenreiche Umsetzung einer bildungspolitischen Innovation. Schriftenreihe SBF.

García, O. 2009. Bilingual education in the 21st century: a global perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Grin, F. and Schwob, I. 2002. Bilingual Education and Linguistic Governance: The Swiss experience. Intercultural Education, 13:4, 409-426.

Lys, I. and Gieruc G. 2005. Etude de la maturité bilingue dans le canton de Vaud: Enjeux, outils d’évaluation et niveaux de compétence. Lausanne: Unité de recherche pour le pilotage des systèmes pédagogiques. 1-176.

Meune, M. 2010. La mosaïque suisse: les représentations de la territorialité et du plurilinguisme dans les cantons bilingues. Politique et Sociétés 29.1, 115–143.

Paternostro, R. 2016. Enseigner les langues dans des contextes plurilingues: réflexions socio-didactiques sur le français en Suisse italienne. Congrès Mondial de Linguistique Française. DOI: https://doi.10.1051/shsconf/20162707012

Stotz, D. 2006. Breaching the Peace: Struggles around Multilingualism in Switzerland. Language Policy. https://doi.10.1007/s10993-006-9025-4

Zimmermann, M. 2019. Prophesying success in the higher education system of multilingual Switzerland. Multilingua2020; 39.3, 299–320

Zimmermann, M. and Häfliger, A. 2019. Between the plurilingual paradigm and monolingual ideologies in the compulsory education system of multilingual Switzerland. Sección Monográfica. Lenguaje y Textos, 49, 55-66

Websites:

Canton du Valais, Kanton Wallis. 2006. Concept cantonal de l’enseignement des langues pour la pré-scolarité et la scolarité obligatoire. Département de l’éducation, de la culture et du sport, service de l’enseignement, Department für Erziehung, Kultur und Sport, Dienstelle für Unterrichtswesen. Available at: https://www.vs.ch/documents/212242/1231591/Concept+cantonal+de+l%27enseignement+des+langues.pdf/c8928ad0-678f-42f6-977c-43e1e4a1d07e. Accessed on: 13.12.2020.

Canton du Valais/Kanton Wallis. 2016. Le collège: la porte ouverte à toutes les professions du niveau supérieur. Available at: https://www.colleges-valaisans.ch/data/documents/Colleges-Valaisans/brochure_maturite_gymnasiale.pdf. Accessed on: 13.12.2020.

Etat de Fribourg/Staat Freiburg. 2020. Bilinguisme dans les écoles du secondaire supérieur et échanges linguistiques. Available at: https://www.fr.ch/formation-et-ecoles/ecoles-secondaires-superieures/bilinguisme-dans-les-ecoles-du-secondaire-superieur-et-echanges-linguistiques. Accessed on: 13.12.2020.

Illustrations:

Figure 1: White B. 2017. Ben White Photography. Available at: https://unsplash.com/photos/qDY9ahp0Mto. Accessed on: 20.12.2020.

Figure 2: Zanoli, M. 2006. Map Languages CH. Available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/. Accessed on: 20.12.2020.

Figure 3: centvues. 2012. Quelque chose a changé, en notre… Available at: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/ce8d781e-d05b-4598-b7e3-5b4acfc80c0c. Accessed on: 22.12.2020.

Figure 4: Serge1958. 2020. Switzerland trilingual and bilingual. Available at https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/94de9b9d-1e99-4f20-b5fa-8d1663ab4622. Accessed on: 22.12.2020.

Further Resources:

Elmiger D. 2020. Inventar des zweisprachigen Unterrichts in der Schweiz / Inventaire de l’enseignement bilingue en Suisse. Université de Genève.

Gohard-Radenkovic A. 2013. Radiographie de l’immersion dans l’enseignement supérieur en Suisse et à l’Université de Fribourg: les pré-requis nécessaires. French immersion at the University level. Vol. 6, 3-19

Langfocus. 2016. Languages of Switzerland – A Polyglot Paradise? Youtube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7p8GgX_hWyA. Accessed on: 20.12.2020

Le Pape Racine C., & Ross K. (2015). Code-Switching als Kommunikationsstrategie im reziprok-immersiven Unterricht an der Filière bilingue (FiBi) in Biel/Bienne (Schweiz) und didaktische Empfehlungen. Journal of Elementary Education, 8(1/2), 93-112.

Schoch, B. 2007. Lernen von den Eidgenossen? Die Schweiz – Vorbild oder Sonderfall? Osteuropa, 57, 27-46