By Flora Tucker

In this blog entry, I investigate the usage of English in J-Pop from a sociolinguistic perspective. This case study will illuminate the phenomenon of English as a foreign language in popular culture.

Keywords: J-Pop, Pop music, Multilingualism, English, Pop culture,

Intro.

First things first: What is pop culture? And why should we care about it? It’s a difficult thing to define, but the Oxford English dictionary defines it as “culture based on popular taste rather than that of an educated elite, usually commercialized and made widely available by the mass media.” Pop culture is often fast changing, and defined by a large number of people in a way that traditional culture isn’t. Often research into it doesn’t proportionally represent the interest that the general public has in it, but this is beginning to be more often a subject of research. From an academic point of view, studying pop culture can inform us about trends and processes, and the world that we live in in real-time .

Lee & Kachru (2006: 191) describe pop culture as a global phenomenon which often has “a remarkably defined local face.” It’s widely accepted that English has become a global language, and as such, it isn’t surprising that it is prevalent in pop culture all over the world – including in Japan, where I will focus – but what happens when the global language meets the “local face”? Does it erase it, change it, or define it? The study of English in pop culture, therefore, can help us understand what happens when the global meets the local, and how communities adopt and mould it. The ‘pop’ in ‘pop culture’ comes, as one might expect, from the ‘pop’ in ‘pop music’, so pop music appears to be a logical place to start. I will be considering J-Pop, which is Japanese pop music, specifically that which is heavily influenced by Western rock and pop. Originating in response to Western rock and pop, J-Pop is therefore a fertile ground for investigating the meeting of cultures, particularly through language. For the purposes of this blog entry, I will be attempting to answer this question: To what extent does English in J-Pop serve as a globalising influence? And what does this mean in terms of the local Japanese identity and Japanese pop culture?

Laying the Groundwork.

I’m approaching this blog post from a sociolinguistic perspective, that is to say, I am interested in the social side of this linguistic phenomenon. The study of English in J-Pop is a relatively small field, with much of the research dating from the 2000s. Very often, this research attempts to define what the role of J-Pop English (J-PopE) actually is. One can see global and local identities often in conflict, through the usage and reception of the language, and it is this angle that I intend to examine.

Now for some key definitions:

J-Pop is Japanese pop music, specifically that which is heavily influenced by Western rock and pop.

Local/Global. While it is tempting to think of the local and the global as two diametrically opposed concepts, often this view relies on pre-existing, stratified identities dependent on nationality or regionality, particularly as regards language. Pennycook (2003) emphasises that this is not a useful way to approach the global and the local. Rather, he emphasises Appadurai’s argument that globalisation is a “deeply historical, uneven and even localizing process. Globalisation does not necessarily, or even frequently mean homogenization or Americanization” (Appadurai, 1996: 17, in Pennycook, 2003: 4).

Though national notions of identity are far from perfect or homogenous, when I refer to “the local” I will be considering Japanese (national) identity, or occasionally East Asian identity. Though J-Pop English might be integrated into notions of the local, one must accept that it comes from Western influences. From the studies reviewed, I will be considering whether its usage tends to promote more transnational ideals, national/regional ones, or a blending of the two.

Code ambiguation is a form of language-blending that produces a phrase that might have meaning in either language (Moody and Matsumoto, 2003: 4).

What’s already been said, then?

(Literature Review)

The Origin Story

The term ‘J-Pop’ was coined in the late 1980s by radio station J-WAVE, which originally played exclusively Western music. Bowing to pressure from its sponsors, J-WAVE was compelled to air Japanese popular music. Rather than playing kayōkyoku, the Japanese popular music of the time, they decided to air Japanese music that was influenced by foreign, Western music that sounded quite different to the old style. This was at first called Japanese Pop, and then J-Pop. (Moody & Matsumoto, 2003: 5–6; Mōri, 2009: 475-6). Mōri considers the “golden period” of J-Pop to be between 1988 and 1998, which explains why much of the significant research dates from the 2000s (Mōri, 2009: 475–6). Much like other East Asian genres, therefore, such as Korean K-Pop, Hong Kongese Cantopop, and Taiwanese Mandopop, J-Pop is “largely defined by the use of Asian languages in conjunction with international pop music styles” (Benson, 2013: 23).

How much J-Pop English are we talking?

Among a number of surveys quantifying the lyrical make-up of Japanese pop music around the millennium, Moody (2000, 2001), in a survey of 307 songs from the Japanese Oricon weekly top-50 charts of 2000, found that almost two thirds of the J-Pop songs were found to contain English lyrics (Moody 2000, 2001 in Moody, 2006: 218). The number seems only to have increased since then. In Oricon’s best-selling CD singles of 2013, out of 100 songs, 72 included English words, phrases, or clauses (Takahashi and Calico, 2015: 868). However, this is not necessarily to say that Japanese audiences have become more interested in Western music. Mōri compares non-Japanese to Japanese charts, and comes to the conclusion that, at the time of writing, “most Japanese audiences… [were] primarily satisfied with listening to Japanese popular music and less interested in western music.” (2009: 477). This is particularly the case compared to the mid 1980s (Mōri, 2009: 477). This does not, however, translate to an exclusive linguistic nationalism, as is shown by the fact that Utada Hikaru’s album Exodus, made for an American audience in English, reached #1 on the Oricon chart, and was popular across East Asia (Benson, 2013: 26). While Western music, therefore, might have declined in popularity in Japan, J-Pop’s popularity has increased, and it contains English lyrics more and more.

Transnational functions of J-Pop English.

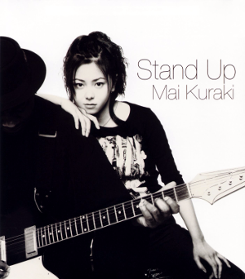

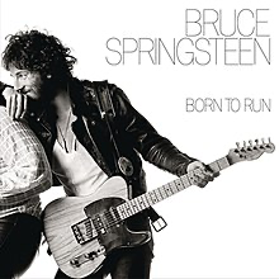

Given the international origins of J-Pop, it is not surprising that questions of global and local identities are highly prevalent in the literature surrounding it. Moody & Matsumoto discuss how the use of English in J-Pop could be seen as a tribute by artists to Western influences (2003: 7–8). Sometimes this is done by adopting English song-titles, or incorporating references into the lyrical body, such as in the case of Wink’s “BoysDon’tCry”. Sometimes this is done through imitative album-art, as in Mai Kuraki’s 2001 single Stand Up which imitates the cover of Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run, below.

Stand Up ©Giza, 2001

Born To Run ©Columbia, 1975

Tribute might also take the form of a Japanese cover of an English song, as Hideki Saijo’s 1979 “Young Man (Y.M.C.A)”, a cover of the English song “Y.M.C.A.”by the Village People. Indeed, this was the first J-Pop song with an English song-title. Similarly, Benson (2013: 24) notes the pattern in East Asian countries where at first foreign music styles are embraced whole-heartedly, in their original language. Then, artists start to compose in that style but in their own, local language. Through this lens, one could read Moody & Matsumoto’s Y.M.C.A. example as a reinvention of English hits as Japanese.

Moody considers how Japanese is used for communication, and English for entertainment, in “language-entertainment” shows (shows which focus on language as a topic) such as ‘‘Eigo-de Asobo’’ [Let’s Play in English] for children or ‘‘Eigo-de Shabera Naito: Can You Speak English’’ for adults, on which J-Pop celebrities are common guests (Moody, 2006: 212–8). Takahashi and Calica note the traditional use of English as a mode of international communication (2015: 870). How, then, does J-Pop English function in a transnational setting (i.e. beyond Japan)? Benson (2013) examines the success of Utada Hikaru’s 2004 album Exodus. After three very successful Japanese albums, she released a second English one, targeted at North American audiences which included the hit ‘Easy Breezy’. ‘Easy Breezy’ was most popular in Japan and Thailand, followed by the United States. It seems then, that its success was still mostly in East Asia or in East Asian diasporas. When examining the YouTube comments section of the music video, Benson argues that the main language of the song being English allowed ‘Easy Breezy’ to reach a wider audience, including non-native English speakers. English, then allows music to surpass linguistic barriers within East Asian regions. In this way, it is both transnational and still in keeping with an East Asian regional identity.

English in J-Pop can also allow a singer to adopt an identity closer to an Anglo-American one. Benson (2013) considers two of “the most frequently viewed East Asian English-language videos of the past decade”, including Utada Hikaru’s ‘Easy Breezy’ (2004). He sets out how Utada acts out a “sexually assertive identit[y]” in comparison to her “softer, more feminine and less sexually assertive identit[y]” in her Japanese language work (28). Similarly, Stanlaw considers how in the Wink’s “Boys Don’t Cry”, the use of English serves to denote how this is “a Western-style romance,” meaning the heartbreak the singer depicts is not actually so serious, and she will be moving on soon, even as she announces how much she suffers (Stanlaw, 2004: 105). The complete and partial use of English in J-Pop may seem like globalisation through the Anglo-Americanisation of the J-Pop singer. As a negative connotation of this, Benson considers recording completely in English to pose risks to artists’ (East-Asian) identities (2013: 32). Rather, he says, it is a tactic used best by bicultural artists, like Utada Hikaru (Benson, 2013). This would seem to denote that linguistic identity-switching is better done in moderation, unless it is already culturally a part of the singer’s identity.

J-Pop and Nationalism

Mōri (2009: 476–8) considers the nationalist aspect of J-Pop, and particularly its ‘J’. She aligns the decreasing popularity of Western music in Japan with the increasing Japanese nationalist attitudes. She considers the return of nationalism as “represent[ing] young peoples’ ambiguous anxiety in the face of a crisis of national identity against globalization” (2009: 476–8). However, she points out the irony in the popularity of J-Pop as a form of nationalism, and goes on to consider “the fantasy of a globalised Japanese culture” i.e. the fantasy of Japanese culture taking on a global status, beyond South East Asian countries and diasporas. Through J-Pop, and particularly J-Pop English, “people could easily enjoy the illusion of a globalized-self”. This “fantasy of a globalised Japanese culture” is rather in contrast to Moody’s (2006) representation of notions of Japanese linguistic and ethnic superiority. Rather, for him, J-Pop challenges a nationalism based upon exclusion; for him through English-Japanese code-ambiguation, linguistic and emotional barriers between J-Pop and Western music are diminished.

The addition of English to Japanese music has not, in fact, changed the themes much from kayōkyoku (Misaki, 2002 in Moody & Matsumoto, 2003: 6). Stanlaw (2004) makes a similar point, when he references the song “Sand Castle” by Yuming. According to him, English is used to refresh and add a new dimension to an otherwise “cliched” song (Stanlaw, 2004: 109). In terms of form, Moody & Matsumoto (2003: 10) show how single words and phrases such as “jump” or “kiss” can be used in an otherwise Japanese text without disrupting the structure. Similarly, some words are merely written in romanji (roman) script, and are therefore counted as English. Moody & Matsumoto (2003) further discuss how in instances of code ambiguation, they are often unnoticeable to those who do not have the script in front of them, because they have meaning in either language. Stanlaw considers how English is used to create rhymes or otherwise complicate structures (2004: 113), and Takahashi & Calico and Moody & Matsumoto consider the playful use of English in J-Pop through linguistic play such as code ambiguation (Takahashi & Calico, 2015: 870–1; Moody & Matsumoto, 2003: 16–7). It is on this playfulness that Stanlaw comments in the song ‘Boys Don’t Cry’, as turning the tragic demise of a relationship into a “love-game”, though the playfulness here is less linguistic and more to do with cultural association (Stanlaw, 2004: 104). When English is used, the sentences are often simplistic and accessible to a Japanese audience(Mōri, 2009: 477; Takahashi & Calico, 2015: 870). The use of English, therefore, does not seem to change much of the fundamentals of Japanese popular music, in terms of structure or subject matter, though of course the lyrics are only one aspect of Western influence in the genre. Rather, English lyrics seem to be adopted more into the formal aspect, ie. the way the song is presented, and used as play in a way that is meant to be understood by a local, rather than national, audience.

What to make of all this?

By nature, the birth of J-Pop was simultaneously global and local; it was a necessary mixing of Japanese music and Western influences. J-Pop’s legacy, and the position of English in it, is similarly global and local. Since its conception in the late ’80s, J-Pop has slowly taken the place of Western music in the Japanese charts, while English has become the most common foreign language used in it (Takahashi & Calico, 2015: 868). J-Pop’s interaction with the West works both as a ‘globalising’ and a ‘localising’ force: sometimes tribute serves to globalise Japanese music, while other times covers serve to render global hits Japanese, or local. Though Anglo-American identities are often partially assumed by singers through their use of English, the complete assumption of an Anglo-American identity in a song tends not to be received so well, unless the J-Pop singer is already bicultural. More commonly, English is used to ambiguate traditional kayōkyoku themes, which remain prevalent in J-Pop, although kayōkyoku has fallen out of fashion. In the face of more nationalistic ideals, J-Pop English appears to be a globalising force, whether it is merely expanding the nationalism to a global stage through a global language or, as seems more likely, blending Japanese culture with other cultural influences, so there is more connection between the two ideals of the global and of the local. Overall, it is overly simplistic to consider J-Pop English to be a globalising force. Rather, it also preserves and plays with local, traditional, themes and ideas, expanding the repertoire of J-Pop artists.

Limitations of existing research in English :/

When considering the use of English in J-Pop, one should consider that the lyrics are only one aspect of any musical work, and much of the research I have considered is dependent on having a lyric sheet – something that is not traditionally part of consuming music. Though this is useful for studying J-pop, it is not representative of the way in which it is consumed, and therefore, experienced. Furthermore, the vast majority of the research in this field seems to come from the 2000s. Even if this was the “golden age” of J-Pop in its strictest, most exclusive, definition, a more liberal definition of J-Pop has evolved, and in the 2010s and 2020, research into the subject is very limited – though I must admit that my access to this research is sadly limited to articles available in English, and so my view of this is Anglocentric. I would encourage more up-to-date research into this topic, as its positioning in a highly competitive, dynamic market reveals a lot about the ideologies of the consumers, as well as the way that Western Culture and East Asian cultures fuse.

Discography

Hikaru, Utada. 2004. Exodus. Island.

Hikaru, Utada. 2004. “Easy Breezy,” Exodus. Island.

Kuraki, Mai. 2001. “Stand up,” Stand Up. Giza Studio.

Matsutouya, Yumi. 1991. “Sand Castle,” Dawn Purple. Universal Music.

Saijo, Hideki. 1979. “Young Man (Y.M.C.A.),” Young man/Hideki Flying Up. RVC.

Springsteen, Bruce. 1975. Born to Run. Columbia.

Village People, The. 1978. “Y.M.C.A.,” Cruisin’. Casablanca.

Wink. 1989. “Boys Don’t Cry,” Boys Don’t Cry. Polystar.

References

Benson, P. 2013. English and identity in East Asian popular music. Popular Music 32.1, 23–33.

Lee, J. S. and Y. Kachru. 2006. Symposium on World Englishes in Pop Culture: Introduction. World Englishes 25.2, 191–193.

Moody, A. J. 2006. English in Japanese popular culture and J-Pop music. World Englishes 25.2, 209–222.

Moody, A. and Y. Matsumoto. 2003. “Don’t Touch My Moustache”: Language Blending and Code Ambiguation by Two J-Pop Artists. Asian Englishes 6.1, 4–33.

Mōri, Y. 2009. J‐pop: from the ideology of creativity to DiY music culture. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 10.4, 474–488.

Pennycook, A. 2003. Global Englishes, Rip Slyme, and performativity. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7.4, 513–533.

Stanlaw, J. 2004. The poetics of English in Japanese pop songs and contemporary verse. In Japanese English: Language and Culture Contact. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 101–126.

Takahashi, M. and D. Calica. 2015. The Significance of English in Japanese Popular Music: English as a Means of Message, Play, and Character. 言語処理学会 第21回年次大会 発表論文集 (2015年3月), 868–871. Society for Natural Language Processing.