An analysis of advertising adaptations to the Swiss multilingual context

Christophe Nascimento Santos and Emmanuel Parriaux

In this article, we explored the subject of the multilingual adaptations made in advertising in the Swiss context.

The Matter:

The many ways multilingualism can be used in advertising have yet to be understood in their entirety. The fact companies reinvent advertising constantly and are very numerous makes it almost impossible to capture every single way multilingualism is used. But without considering the number of companies doing it, the mechanisms behind the use of multilingualism remain complicated in and of themselves due to the multiple forms they can take. Multilingual advertising takes several forms depending on the context: word for word translation from one language to another, colloquial language-mixing, professional uses of multilingualism to only mention a few. The study of the use of multilingualism concern languages considered both “foreign” and “national”. Companies are interested in this subject to make their advertising campaigns more effective. Scholars are also interested in this subject to study how advertising shapes our perception and influences our behavior despite having to pass through a language barrier. This makes it a very relevant and interesting subject, ripe for inquiry. In this blog entry, we will try to understand the ways compagnies like the Coca-Cola company structure themselves in regards to multilingual discourse, and how they react to the demands of the market for multilingual advertising. We will take an interest in how identity is constructed through advertising in different media, through the article of Ingrid Pillar (2001) and others and interest in how languages are perceived in the context of inter and intra-national exchanges. We will further focus our inquiry on countries where multiple national languages coexist. We will focus especially on the situation in Switzerland, while taking into account relevant knowledge linked to studies explaining how advertisements from English-speaking (mostly U.S-based) companies try to gain more reach in non-English-speaking countries. We will also not discard studies of other countries sharing some similarities to the case of Switzerland like Québec. To this end, we will critically review the available literature on this topic

In this entry, we will discuss the way advertising agencies in Switzerland handle the multilingual specificity of the country. The first concept we have to define is “multitext”, this concept regroups all the different characteristics of advertising, like the main text, the visual information and the interactions with the cultural context. “Quantitative” and “qualitative” research are two approaches to collect and to analyze data. Quantitative data represents a very broad gathering of non-complex information, it is chosen when the goal is to obtain a very representative result, with big sample sizes. Qualitative data represents a narrow gathering of complex information but a deep analysis of a answers. Sociolinguistics is the study of the effects of our society on the language we use, and how we use language in society. It is linked to the study of cultural norms and expectations. Semiotics is the study of the meaning we understand through signs. Social semiotics is the study of the meaning we create and understand socially through codes of conduct or of speech.

Literature review

Advertising is a special kind of media in that it is mostly unregulated. Where official communication is delimited by the state’s laws and informational medias’ goal like television and radio is to convey both information and enjoyment to their public, commercial advertising is only driven by one simple goal: selling products . This profit seeking goal is the only factor that will decide the fate of an advertisement campaign. Therefore, it is also the main element we shall look into when discussing the choices made by the advertisement agencies in a multilingual environment.

There seems to be a certain consensus in the linguistic scholar community on the idea that advertising, maybe more than some other forms of expression, is an important subject to study. Because it is either understood as a gateway to the way people represent themselves or as a building block of societal identity-making and norm-setting. Multilingualism in this context is often used to try to appeal to a certain social class. Piller (2001) in her article Identity constructions in multilingual advertising uses as an example a German ad for a company that sells German leather bags. The ad is addressed to middle to high-middle class businessmen and woman and embodies the presumed characteristics and values of this class (tradition, efficiency, valorization of high-status). On that specific bag, the name of the company is written in English rather than German which clashes with the rest of the ad which is otherwise entirely in German. This adds the sense that knowing and using English in an international business environment is something of value and to be proud of. In that sense, it constructs or reinforces the perceived and lived identity of its consumers while the company only seeks to sell a product. This shows how the use of languages perceived as non-native is a tool used in advertising to build or/and appeal to certain social groups and communities through the consumer images. Multilingualism here meets its corporate side again.

It is sometimes better for companies to try and break into a new linguistic market environment than to try to expand its consumer base in its country of origin. This creates a need for those companies to translate their offers in a new language. A consideration we have to make concerning this need for a translation is the different kinds of agencies that exist and whether or not all agencies deal with this issue in a similar way. In his article “La traduction dans les agences de publicité”[1], Philippe Emond (1976) distinguishes three different scales of advertising agencies. First, we have the bigger ones that he calls the “commercial agencies”. These represent the leaders on the market, the biggest companies, and especially the ones whose marketplace is the largest, often trespassing national and linguistic borders. For this reason, they are the kind of agencies that are often confronted with multilingualism and have to decide to create, or not, translations. Another big characteristic is that they possess a varied activity sector and that their audience is wide. The second type is called “industrial agencies”, as they represent agencies that operate in a more specific market. They are often specialized in a single domain, as pharmaceuticals for example, and sell their products not to individuals but to companies. Therefore, their public range is narrowed to an audience of specialists. They communicate with people who have a clear budget, have researched all the competitors, know what they specifically want, and are not as easy to convince as a more general audience. The discourse these industrial agencies use is then more technical and informational. The different characteristics of the products have to be visible and the content is more important than the form, where the commercial agencies often prefer the form. In this specialist discourse, where providing clear information is key, the use of translators is more common. The last category is called the “promotional agencies”. They are the smaller agencies which work on very specific projects like the organization of a supermarket for example. Our work will only marginally consider this kind of ads as their use of translation is very limited

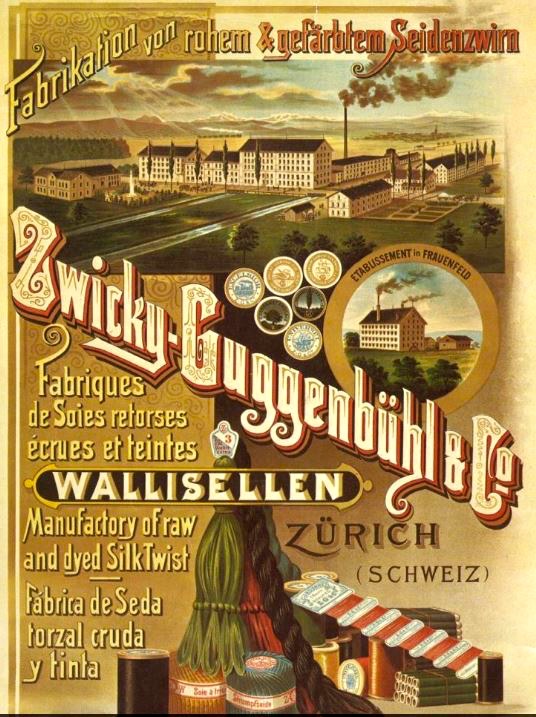

The way in which commercial agencies deal with the multilingual aspect of their audience has largely changed over time. We already see in the article of Emond (1976), that a particular strategy was starting to gain traction: creating smaller “daughter enterprises” that are focused on relaying the campaigns from the main company in their specific linguistic territory, a subsection in France or the whole French-speaking world for example. This strategy is mainly used nowadays for major agencies, but the smaller ones still use translators directly from the main company. This change corroborates the evolution of advertisement translations. Since the early days of mass advertising in the 1950s, the campaigns focused on the product and its characteristics. But they slowly tended to shift this focus towards the effect the advertising had on the consumer and marginalize the factual information. As Guidère (2009) says it: “the translator’s interest shifted from the “source” to the “target” (personal translation). Therefore, the translation did not stop itself from the simple translation of the words in the ad but continued to the localization of the whole campaign to the audience’s culture, what Guidère (2009) calls the “multitext”. For example, a campaign in India will feature people of Indian ethnicity, but the same ad will change its characters for European looking people when imported in Europe.

The Swiss context displays special characteristics relative to its very own “multitext” as every singular place has its own. To understand better Switzerland and the use of multilingualism in multinational compagnies we looked at examples of attempts by compagnies to reach out to countries with multiple national languages. Doing so, we’ve seen that the use of French by English-based agencies in Quebec, is made to profit on the desire for independence of the Quebecois. In this case, the linguistic question is very political and debated. This requires further examination: Through a sociolinguistic and social semiotic lens, Elizabeth Martin (2011) studies the attempt by American fortune 500 companies to appeal to a French-speaking audience on the internet. With the support of both quantitative and qualitative data she noted that the most successful attempts were those that attempted more than a mere, raw, word-for-word translation of the English website (which was not effective, especially in Quebec) and instead tried to connect more closely to the audience of those countries through efforts to connect their brand to culturally relevant events. (Hockey players at the Olympics for Canada to take one example) and limited their use of English to marketable slogans or suppressed it entirely based on how resistant the populations were to the use of English. This showed how advertising connected deeply with both the concept of identity and cultural norms and how important it was not to adopt a “One size fits all” approach. Yet, the study highlighted nonetheless that many companies still followed a blind front-cost-cutting standardized approach that does not fulfill their goals in the long run. This study highlighted both the successes and failures of companies and suggested localization was a preferable alternative to export one’s product.

In Switzerland, multilingualism, even though very present, is not very debated and the political tensions between linguistic communities are quite light. Grin and Korth (2005) outlined that the Swiss were “overwhelmingly in favor of developing access to English for all children in the education system” But this favor put the other national languages in a peculiar situation: “Should [the national languages] be given more or less importance than English, or should they be on par?” Maybe this lack of resistance to English has created the lack of a need to create culturally relevant advertising for the different Swiss populations and heavy reliance on a word-for-word kind of translation. This causes problems especially when we know of the relative conservatism that swiss advertising agencies possess in Switzerland. Its effects are definitely visible. As an example, the translations from German to French, (almost never the other way around), are only made on the simple text and not on the whole multitext. Advertisements made by Germanophones will often play on traditional values like family and feature personalities only known in the Swiss-Germanic part of Switzerland and they will not be adapted at all to sociopolitical values and identities more common on the other side of the Rösti Graben.

Conclusion:

As we have seen, advertising is an industry guided by monetary demands. Yet it shapes people’s behaviors as consumers and as member of classes because of its setting of norms. We build our consumer identities partly in response to it. We have explored how marketing agencies are built and the different strategies they use to manage the transmission of their information to us depending on their needs and to which social class they are marketing their products for. We examined how companies tried to break the language barrier and how they attempted to cater to different linguistic communities. Sometimes they did so with great success through a localized understanding of the cultural and linguistic territory. Other times it was a great failure through standardized cold and lifeless, “one size fits all” procedures. Methods based on word for word translation to approach communities who sometimes feel invaded by a product they resent as out of place or as “not belonging” just work significantly less. We then focused on the case of Switzerland where it seems to us that companies have done a pitiful job of connecting with the rich multilingual potential of the multilingual country and transmit advertisements that feel out-of-touch with the perspective of many Swiss citizens. There is a lot left to learn on the subject and more research is needed. The studies we approached often noticed the lack of representation of certain communities on the global scene where the advertising they received was always very generic and sometimes not even translated. It is therefore difficult for us to learn about what is happening in those communities and we think in the future, as those markets develop and awareness of their presence on the global scene grows, inquiry on how global marketing will make its way, or perhaps fail to make its way, in a localized manner will be very interesting to look at.

AMOS, W. 2020. English in French Commercial Advertising: Simultaneity, bivalency, and language boundaries in Journal of Sociolinguistics, 24 (1), 55-74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12386

BOIVINEAU, R. 1972. Que pense-t-on de l’adaptation publicitaire en Belgique et en Suisse? In Meta, 17 (1), 47–51. DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/002098ar

EMOND, P. 1976. La traduction dans les agences de publicité in Meta, 21 (1), 81–86. DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/002708ar

FORUM, Le grand débat (vidéo) – Les pubs suisses sont-elles vraiment si nulles ? RTS Info, 11.12.2020, 18h31-18h50. Available at : Forum (vidéo) – Le grand débat (vidéo) – Les pubs suisses sont-elles vraiment si nulles? – Play RTS

GRIN, F., KORTH, B. 2005. On the reciprocal influence of language politics and language education: The case of English in Switzerland. Lang Policy 4, 67–85. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-004-6565-3

GUIDERE, M. 2009. De la traduction publicitaire à la communication multilingue in Meta, 54 (3), 417–430, p.420. DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/038306ar

MARTIN, E. 2011. Multilingualism and Web advertising: addressing French-speaking consumers in Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 32 (3), 265-284. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2011.560671

PILLER, I. 2001. Identity construction in multilingual advertising in Language in society, Vol.30 (2), p.153-186. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404501002019