The Practical Organization of Languages in Multilingual Restoration Businesses on César-Roux Street

Authors: Yael Bignens and Tim Nguyen

Abstract:

The focus of our research was based on the hierarchisation of languages in multilingual restoration businesses located on Dr César-Roux Street, in Lausanne. Bottom-up signs of three different businesses and interviews with the owners were used in order to conduct our analysis. Based on observation, we noticed that French signs (official language of the area) were used in order to convey essential information towards customers. Through interviews, we could observe that it was also more valued in order to target a wider clientele and due to its expansion in the area. Concerning immigrant languages, their use appears as being a claim for their cultural identity and to introduce new culinary concepts in Switzerland with no specific aim to target an expatriate clientele. English was very little used against our expectations. However, its use aimed to attract tourists and expatriates.

Introduction:

Switzerland has since long been multilingual with its four official languages spoken in respective parts of the country. Furthermore, it received several migration waves, i.e. the Italian and Spanish migration during the Cold War and Yugoslavian migration during the Balkan war, which considerably increased the spectrum of multilingualism. Participation in the economy of the host country led to the emergence of multilingual businesses. The focus of this essay is, by means of short interviews with owners of multilingual restoration businesses in Lausanne and photographs of shop fronts, to investigate the use of multilingualism and the organization of languages in these businesses i.e. the selection of different languages and their aims. As such, this essay provides an analysis of the hierachisation of languages in restaurants with multilingual written signs. Previous studies have already dealt with the subject of hierachisation of languages on the labour market (Duchêne 2011). Although hierachisation of languages was not central to this article, we took it as a starting point for our paper. This essay will focus on the use of multilingualism in restaurants located on César-Roux Street and its use to convey practical information.

This paper is structured as follows: the first section will outline the focus of this essay as developing concepts that have been discussed in previous studies and will be used again in our research. The second section presents the method and data used. The third section displays our results while in the fourth section we will provide an interpretation of these observations.

Theoretical Framework

As claimed by Mooney and Evans, “advertising billboards, posters and handwritten notice […] are all parts of our linguistic landscape” (Mooney and Evans 2015: 87). The top-down signs are to be differentiated from the bottom-up signs in order to “draw a distinction between official and non-official signs”. As such, this difference provides an idea about the producer of the sign. Since “top-down signs” are most of the time produced by authorities such as institutions or the government, they can be described as “official” and are in most cases written in national languages.

As opposed to that, “bottom-up signs” are produced by individuals or smaller group and are therefore more flexible in terms of language choice. Our study investigates the use of multilingualism in restoration businesses located in Dr César-Roux Street. Their signs are produced by their owners and can be described as “bottom-up”. The choice of the use of multiple languages implies a language hierachisation i.e. the value one language has in comparison to other languages following language ideologies (Mooney & Evans, 2015: 87).

The topic of language hierachisation has already been discussed in earlier studies which highlighted the rules of the labour market it followed. Duchêne (2011) shows that the languages that were the most previsible (i.e. the languages the most spoken throughout the customers) appeared to be the most valued in the visible jobs i.e. the jobs that require contact with customers. Being able to fulfil their customers’ needs thanks to the linguistic skills of the employees, the company thus profited from an added value which was not financially supported. As a matter of fact, the company required their employees to master linguistic skills that participate neither in the acquisition, nor to maintain them. As such, the article highlights the relationship of commercial exploitation of their employees’ linguistic skills (Duchêne 2011). In our research, our aim is to find out the planned strategy of language hierachisation chosen by the owners of restoration businesses, by analyzing the choice of different languages to convey different set of information and the way it is displayed in the space.

Contextualisation

For the purpose of this study, we decided to focus on Dr César Roux Street, situated in the East-Lausanne neighbourhood of Valon/Béthusy in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland, in which the official language is French. According to the Office d’appui économique et statistique, the inhabitants are for the majority aged from 20 to 39 years old and a large number of the households is constituted of a single person. By walking within this area which is about 10 minutes walk from the city centre of Lausanne, we realized that the neighbourhood had an important concentration of businesses according to space (including many grocery stores, hairdressing salons, and tattoo salons). This area seems a bit less lively than the city centre as it is located a bit further away. Therefore, this area appears less touristy or at least, the businesses do not appear to serve a high number of tourists. These three multilingual businesses were situated next to each and raised our awareness on the immigrant population rate in Switzerland. It would be interesting to observe specifically the rate of nationalities that correspond to the immigrant language labelled on each shop window that we decided to analyze.According to Lausanne: portrait statistique, the Italian represented 4,6% of the overall population of Lausanne in 2017. However, these statistics did not reveal the rate of the Lebanese and Thai population, as they were listed “other nationalities”. Although nationalities do not reflect the linguistics ability of the speakers, we could use these statistics as a way to globally estimate speakers of non-official languages. Moreover, according to estimations of the “structural survey” of 2016, more than 80% of the population use French as first language.

Method

As first assessment, we created a corpus of ten pictures with a presence of multilingualism in the neighbourhood and uploaded them to a Google map document. It allowed us to realize that the specific street of Dr César-Roux appeared as having a consequent concentration of bilingual businesses. From this corpus, we selected three pictures of restaurants relevant to our study and localized in this street. We based our analysis on them, because in our opinion, they showed diverse linguistic features i.e. presence of non-official languages only or more than one language on the shop windows. However, we realized that our analysis was mostly based on presumptions as we only looked at the outside of these businesses.

We decided therefore to conduct interviews in French with the owners of the different places in order to understand the language selection for each set of information addressed to customers. The interviewees were informed of the purposes of the study and gave us permission to use the data for scientific purposes, to be recorded and to post it online.Two of them accepted to answer a couple of questions we previously prepared concerning the languages used outside and inside their place and its organization (cf. Appendix B), as well as being recorded. The last owner was not open to discussion; therefore we decided to base our analysis on our own interpretations on the basis of what we could observe in the linguistic landscape. Secondly and with the support of our scripted interviews, an analysis was made based on the owners’ declarative data in order to explain why the different languages were used.

Results and Discussion

Through the diverse pictures taken and displayed in Appendix A, the results of this study showed that the signs used were each bottom-up signs. French signs and information in the three multilingual businesses selected in the Dr César-Roux street were used to convey essential information to customers, such as opening hours (Figures 3, 7, 13) and to provide a translation of the composition of dishes (Figures 2, 8, 9) and explanation of a photograph (Figure 11). The size of the French signage was inconspicuous, although placed in visible areas i.e. the entrance of businesses or close to the checkout.

Based on the interviews of the Italian restaurant Amici and the Lebanese restaurant Man’Ouchy’s owners displayed in Appendix B, we could observe that the owners considered French as being very important according to the official French speaking localisation and because of its expansion which makes it convenient for communication. Indeed, only few customers are not able to speak French in this neighbourhood. In addition to that, both owners affirmed that this language was used in order to target a wider clientele given that it should be understood by everyone and not only expatriates. French would be therefore valued because it is the local language that mostly everyone is able to speak. Concerning the Thai restaurant Pla Tu Thong, important information in small font in the front door was also conveyed in French, such as the opening hours and the refusal of the credit card (Figure 13). The concept of take-away meals was also conducted in French and with a more massive font (Figure 12). Since we could not conduct any interview with the Pla Tu Thong’s owner, we assumed that the place was perhaps too confined to welcome many customers. This could explain the imposing size of the French take-away sign in the shop window which is probably supposed to influence as many customers as possible to take dishes back home. French was consequently valued in these businesses because it remains the official language of the canton of Vaud and in order to target a wider clientele and not only from a given migrant community.

Immigrant languages appeared also as being used in these three businesses. As a matter of fact, Italian, Arabic and Thai were used in the outside facades and the spaces inside, firstly, in order to label the businesses in colourful font and secondly, in smaller one, to label the dishes and their composition in the menu and for decoration.

Based on the observation of the pictures, we supposed that it was used to claim the immigrant identity of the businesses because of the use of authentic products and dishes translated into different languages, as well as the exposition of authentic national products such as wine (Figure 5), tea and handcrafts (Figures 10 & 11). Thereafter, our interviews gave us an insight of the owners’ immigrant backgrounds. The use of Italian for the name of the restaurant and the slogan as well as for the name of its dishes, in the case of Amici aimed to show a new concept to the clientele by translating the previous French name of the place “le Café des Amis”, but also and as expected, to demonstrate the use of authentic products and the Italian-known hospitality i.e. the Italian slogan on the shop window.

In the case of Man’Ouchy restaurant, it was more difficult to make assumptions due to our lack of knowledge about the Arabic variety. After a few searches on the Internet, we could find that the Man’Ouché was a Lebanese specialty restaurant. Through the interview conducted with the owner of the place, we could observe that the Arabic language was used to claim the identity of the business. As matter of fact, the name of the restaurant is a pun only understood by Lebanese as it is a compound the Lebanese pizza (Man’Ouché) and a popular quarter in Lausanne (Ouchy), i.e. a sort of private joke addressed to the Lebanese community. In this way, although not targeting specifically the Lebanese expatriate clientele, Man’Ouchy still claims their cultural identity towards these customers. Furthermore, the owner wanted to introduce this specialty to Switzerland i.e. including local customers, and make it known in a much wider outlook. Names of dishes are also written in Arabic (cf. Appendix A, Figure 8), in order to label authentic products. Some quick translations are provided in a separate sign. By using a word game as a label of the business and authentic names throughout the menu, the Lebanese variety in this context is used to claim an authentic identity inside the business and to differentiate itself from the competitors.

In the case of the Pla Tu Thong restaurant, the use of Thai language is used in order to label the business. However, the abugida is not the Thai original alphabet, but the Latin one. In our opinion, this option could help people realise the actual pronunciation of the business’ name, therefore targeting a wider local clientele. We did not have the opportunity to observe if Thai was used in the inside and on the menu.

In these three multilingual businesses, the use of English was made only by the Lebanese restaurant’s owner within the slogan (cf. Figure 6). In fact, he made this choice in one hand because of his personal bilingual education and in the other hand in order to possibly target international customers. However, advertisements and communication were not conducted through this language, as the neighbourhood appears not to be too touristy. In the case of the Amici restaurant, the use of English was nonexistent in any signage, only in orality in broken English and with help of gestures due to the owner’s lack of knowledge about this language and the pretext that the neighbourhood was not attracting many tourists.

The results of this study have proven some of our presumptions, while the interviews provided information that we would not have thought of otherwise. The immigrant language of each business is used to label the cultural identity of the owners and the businesses, not necessarily to aim the Lebanese expatriate clientele as we thought but principally claim their immigrant identities to the local population which constitutes the vast majority of the clientele of these three businesses. The low influx of tourists is mainly due to the peripheral location of the street; hence very few English features are displayed within the linguistic landscape of this area. Moreover, statistics demonstrate that nearly 80% of the local population use French as first language. Therefore, the three businesses logically use French as means of conveying practical information, since they rarely encounter customers who are not able to speak French.

Conclusion

The main finding of this study includes the discovery of the different functions and values of French (official language in VD) and immigrant languages associated with the ethnic background of the owner and the business in non touristy areas such as César Roux Street. Surprisingly we did not encounter as many English features as expected within the linguistic landscapes of the businesses we studied but this was due to the fact that, being located outside of the touristy area, the clientele of these businesses was mainly local. The large majority of the local population’s first language is French, therefore this language is the most valued and is used to convey most of information i.e. the value given to French is equal to its previsibility. As such, the hierarchy of languages follows the same logic as in Duchêne’s article (Duchêne 2011). However, the immigrant languages are used in order to claim and commodify the owners’ cultural identity, as opposed to the case of Duchêne’s article, in which the immigrant languages, although exploited and benefiting the company, were not given value by the employers. These two cases are very different, considering that the nature of these multilingual businesses is different from the airplane company of Duchêne’s article. Moreover, the employers of the airplane company and the owner of the businesses have different perspectives of immigrant languages, which explain the difference in the aim of their use. For further research, it would be interesting to analyse the use of multilingualism in multilingual businesses in areas in which there are more than one official language or in more touristy areas. As such, we could observe whether the hierarchy of languages fluctuates in such cases or remains stable.

In conclusion, we confirmed the hypothesis that the immigrant language used by the owners of these multilingual businesses was aimed to claim their cultural identity, while practical information is addressed in the official language of the local population which constitutes the majority of the clientele of these businesses i.e. the most predictable language: French.

References

Duchêne, A. 2011. Neoliberalism, social inequalities, and multilingualism: the exploitation of linguistic resources and speakers. Langage et société 136.2, 80-108.

Evans, B. and Mooney, A. 2015. Language, Society and Power: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Office d’appui économique et statistique. 2017. Lausanne: portrait statistique

Available at: https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/portrait-statistique.html

Office d’appui économique et statistique. 2017. Présentation des quartiers Vallon/Béthusy

Available at:https://www.lausanne.ch/officiel/statistique/quartiers/presentation- des-quartiers/10-vallon-bethusy.html

Appendix A

Figure 1. Italian signage at Amici restaurant.

Figure 1. Italian signage at Amici restaurant.

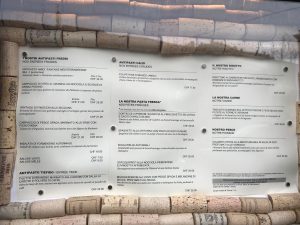

Figure 2. Italian and French menu displayed outside the Amici restaurant.

Figure 3. French information about opening hours displayed outside the Amici restaurant.

Figure 4 & 5. Inside placeand Italian wine exposed in Amici restaurant

Figure 6. Modern standard Arabic, English and French signage on Man’Ouchy’s facade.

Figure 7. French information about opening hours displayed outside the Man’Ouchy restaurant.

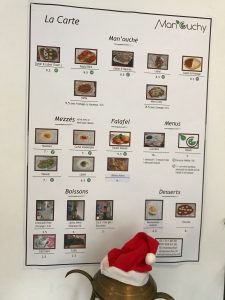

Figure 8. Arabic and French menu displayed inside the restaurant Man’Ouchy.

Figure 9. French signage explaining the composition of the Lebanese dishes.

Figure 9. French signage explaining the composition of the Lebanese dishes.

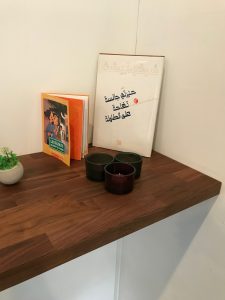

Figure 10. Lebanese handicrafts products exposed for selling in Man’Ouchy restaurant.

Figure 11. Lebanese tea packages for selling and Arabic signage. On the wall, a photograph of a painted building’s wall in Lebanon after war.

Figure 12. French and Thai signage on Pla Tu Thong’s facade.

Figure 13. French information about opening hours displayed outside Pla Tu Thong restaurant.

Appendix B

Translation of the interview conducted with the owner of the Italian restaurant

Amici:

- We saw that your restaurant’s name was “Amici”, does it have any meaning for you?

- Yes, the meaning comes from the earlier owners. Before, in the 70s, 80s, this establishment was called “Café des Amis” (Friends’ Café). It is a bit historical, everyone knew this place, because an institution laid behind. So, we wanted to change the name, in order to show to people that there was a new concept, a new cuisine, that a new establishment was going to open. But we didn’t want to lose the history of “Café des Amis”. Therefore, we decided to translate it from French to Italian: restaurant “Café des Amis” to “Amici”.

- The fact that you translated it was for you to confirm an Italian identity?

- Yes, and to show that here, we do Italian cuisine with Italian products.

- What about the slogan “l’ospitalita italiana”?

- We discussed this idea with my wife, it is our concept to give a hospitality like in Italy. The image, it’s because friends always do handshake to cheer and it has become our logo.

- The menu written in Italian with the French translation, what is that for?

- In order to show that it is based on Italian products, to confirm an Italian identity.

- So, do you target mostly Swiss or expatriate customers?

- Everyone: expatriate, Italian, local…

- Do you have any English translation as well?

- No, not really, we come up to the tables in order to explain a bit, but we don’t speak very well… But we can understand each other with gestures.

- French is therefore to vehicle essential information?

- Of course, the language here is French. We don’t want to have to explain to each table the composition of dishes. It’s not a very touristic area, just a few people do not speak neither Italian or French.

Translation of the interview conducted with the owner of the Lebanese restaurant Man’Ouchy:

- Your place is called “Man’Ouchy”, it is a Lebanese pizza, right?

- Exactly, it is a word game. My specialty is the Lebanese Man’Ouché and as we’re in Lausanne, we made a word game with Man’Ouchy. Lebanese understand straight forward, especially when they see the picture of the Man’Ouché on the truck. The others ask if we have a restaurant in Ouchy.

- Does this name target a population of Lebanese culture or not necessarily?

- Lebanese understand the game word, but we wanted to introduce the Man’Ouché in Switzerland. There are many traditional Lebanese restaurants, but we’re the first to introduce this specialty here. The idea was to make it known in Switzerland.

- We noticed that your slogan on the shop window was in English, what is the reason to that?

- First of all, I am an English speaker. In Lebanon, education is not given in Arabic as many people believe, but a lot in French and English. Secondly, there are many Lebanese restaurants in Geneva which target international customers. English and American people appreciate Lebanese food and are therefore a target for us. But until now, I have never used the English language through communication and social medias. Communication and advertisement through these networks are essentially made in French. English would eventually help us to reach these customers.

- Would English be used to attract international customers?

- But here in Lausanne, we mostly target French speakers. Therefore, we tried to “francophonised” the menu. Names of dishes are in Arabic, but the signage against the other walls explain the composition of dishes entirely in French.