Category: Switzerland

To be or not to be localized, that is the question

An analysis of advertising adaptations to the Swiss multilingual context

Christophe Nascimento Santos and Emmanuel Parriaux

In this article, we explored the subject of the multilingual adaptations made in advertising in the Swiss context.

The Matter:

The many ways multilingualism can be used in advertising have yet to be understood in their entirety. The fact companies reinvent advertising constantly and are very numerous makes it almost impossible to capture every single way multilingualism is used. But without considering the number of companies doing it, the mechanisms behind the use of multilingualism remain complicated in and of themselves due to the multiple forms they can take. Multilingual advertising takes several forms depending on the context: word for word translation from one language to another, colloquial language-mixing, professional uses of multilingualism to only mention a few. The study of the use of multilingualism concern languages considered both “foreign” and “national”. Companies are interested in this subject to make their advertising campaigns more effective. Scholars are also interested in this subject to study how advertising shapes our perception and influences our behavior despite having to pass through a language barrier. This makes it a very relevant and interesting subject, ripe for inquiry. In this blog entry, we will try to understand the ways compagnies like the Coca-Cola company structure themselves in regards to multilingual discourse, and how they react to the demands of the market for multilingual advertising. We will take an interest in how identity is constructed through advertising in different media, through the article of Ingrid Pillar (2001) and others and interest in how languages are perceived in the context of inter and intra-national exchanges. We will further focus our inquiry on countries where multiple national languages coexist. We will focus especially on the situation in Switzerland, while taking into account relevant knowledge linked to studies explaining how advertisements from English-speaking (mostly U.S-based) companies try to gain more reach in non-English-speaking countries. We will also not discard studies of other countries sharing some similarities to the case of Switzerland like Québec. To this end, we will critically review the available literature on this topic

In this entry, we will discuss the way advertising agencies in Switzerland handle the multilingual specificity of the country. The first concept we have to define is “multitext”, this concept regroups all the different characteristics of advertising, like the main text, the visual information and the interactions with the cultural context. “Quantitative” and “qualitative” research are two approaches to collect and to analyze data. Quantitative data represents a very broad gathering of non-complex information, it is chosen when the goal is to obtain a very representative result, with big sample sizes. Qualitative data represents a narrow gathering of complex information but a deep analysis of a answers. Sociolinguistics is the study of the effects of our society on the language we use, and how we use language in society. It is linked to the study of cultural norms and expectations. Semiotics is the study of the meaning we understand through signs. Social semiotics is the study of the meaning we create and understand socially through codes of conduct or of speech.

Literature review

Advertising is a special kind of media in that it is mostly unregulated. Where official communication is delimited by the state’s laws and informational medias’ goal like television and radio is to convey both information and enjoyment to their public, commercial advertising is only driven by one simple goal: selling products . This profit seeking goal is the only factor that will decide the fate of an advertisement campaign. Therefore, it is also the main element we shall look into when discussing the choices made by the advertisement agencies in a multilingual environment.

There seems to be a certain consensus in the linguistic scholar community on the idea that advertising, maybe more than some other forms of expression, is an important subject to study. Because it is either understood as a gateway to the way people represent themselves or as a building block of societal identity-making and norm-setting. Multilingualism in this context is often used to try to appeal to a certain social class. Piller (2001) in her article Identity constructions in multilingual advertising uses as an example a German ad for a company that sells German leather bags. The ad is addressed to middle to high-middle class businessmen and woman and embodies the presumed characteristics and values of this class (tradition, efficiency, valorization of high-status). On that specific bag, the name of the company is written in English rather than German which clashes with the rest of the ad which is otherwise entirely in German. This adds the sense that knowing and using English in an international business environment is something of value and to be proud of. In that sense, it constructs or reinforces the perceived and lived identity of its consumers while the company only seeks to sell a product. This shows how the use of languages perceived as non-native is a tool used in advertising to build or/and appeal to certain social groups and communities through the consumer images. Multilingualism here meets its corporate side again.

It is sometimes better for companies to try and break into a new linguistic market environment than to try to expand its consumer base in its country of origin. This creates a need for those companies to translate their offers in a new language. A consideration we have to make concerning this need for a translation is the different kinds of agencies that exist and whether or not all agencies deal with this issue in a similar way. In his article “La traduction dans les agences de publicité”[1], Philippe Emond (1976) distinguishes three different scales of advertising agencies. First, we have the bigger ones that he calls the “commercial agencies”. These represent the leaders on the market, the biggest companies, and especially the ones whose marketplace is the largest, often trespassing national and linguistic borders. For this reason, they are the kind of agencies that are often confronted with multilingualism and have to decide to create, or not, translations. Another big characteristic is that they possess a varied activity sector and that their audience is wide. The second type is called “industrial agencies”, as they represent agencies that operate in a more specific market. They are often specialized in a single domain, as pharmaceuticals for example, and sell their products not to individuals but to companies. Therefore, their public range is narrowed to an audience of specialists. They communicate with people who have a clear budget, have researched all the competitors, know what they specifically want, and are not as easy to convince as a more general audience. The discourse these industrial agencies use is then more technical and informational. The different characteristics of the products have to be visible and the content is more important than the form, where the commercial agencies often prefer the form. In this specialist discourse, where providing clear information is key, the use of translators is more common. The last category is called the “promotional agencies”. They are the smaller agencies which work on very specific projects like the organization of a supermarket for example. Our work will only marginally consider this kind of ads as their use of translation is very limited

The way in which commercial agencies deal with the multilingual aspect of their audience has largely changed over time. We already see in the article of Emond (1976), that a particular strategy was starting to gain traction: creating smaller “daughter enterprises” that are focused on relaying the campaigns from the main company in their specific linguistic territory, a subsection in France or the whole French-speaking world for example. This strategy is mainly used nowadays for major agencies, but the smaller ones still use translators directly from the main company. This change corroborates the evolution of advertisement translations. Since the early days of mass advertising in the 1950s, the campaigns focused on the product and its characteristics. But they slowly tended to shift this focus towards the effect the advertising had on the consumer and marginalize the factual information. As Guidère (2009) says it: “the translator’s interest shifted from the “source” to the “target” (personal translation). Therefore, the translation did not stop itself from the simple translation of the words in the ad but continued to the localization of the whole campaign to the audience’s culture, what Guidère (2009) calls the “multitext”. For example, a campaign in India will feature people of Indian ethnicity, but the same ad will change its characters for European looking people when imported in Europe.

The Swiss context displays special characteristics relative to its very own “multitext” as every singular place has its own. To understand better Switzerland and the use of multilingualism in multinational compagnies we looked at examples of attempts by compagnies to reach out to countries with multiple national languages. Doing so, we’ve seen that the use of French by English-based agencies in Quebec, is made to profit on the desire for independence of the Quebecois. In this case, the linguistic question is very political and debated. This requires further examination: Through a sociolinguistic and social semiotic lens, Elizabeth Martin (2011) studies the attempt by American fortune 500 companies to appeal to a French-speaking audience on the internet. With the support of both quantitative and qualitative data she noted that the most successful attempts were those that attempted more than a mere, raw, word-for-word translation of the English website (which was not effective, especially in Quebec) and instead tried to connect more closely to the audience of those countries through efforts to connect their brand to culturally relevant events. (Hockey players at the Olympics for Canada to take one example) and limited their use of English to marketable slogans or suppressed it entirely based on how resistant the populations were to the use of English. This showed how advertising connected deeply with both the concept of identity and cultural norms and how important it was not to adopt a “One size fits all” approach. Yet, the study highlighted nonetheless that many companies still followed a blind front-cost-cutting standardized approach that does not fulfill their goals in the long run. This study highlighted both the successes and failures of companies and suggested localization was a preferable alternative to export one’s product.

In Switzerland, multilingualism, even though very present, is not very debated and the political tensions between linguistic communities are quite light. Grin and Korth (2005) outlined that the Swiss were “overwhelmingly in favor of developing access to English for all children in the education system” But this favor put the other national languages in a peculiar situation: “Should [the national languages] be given more or less importance than English, or should they be on par?” Maybe this lack of resistance to English has created the lack of a need to create culturally relevant advertising for the different Swiss populations and heavy reliance on a word-for-word kind of translation. This causes problems especially when we know of the relative conservatism that swiss advertising agencies possess in Switzerland. Its effects are definitely visible. As an example, the translations from German to French, (almost never the other way around), are only made on the simple text and not on the whole multitext. Advertisements made by Germanophones will often play on traditional values like family and feature personalities only known in the Swiss-Germanic part of Switzerland and they will not be adapted at all to sociopolitical values and identities more common on the other side of the Rösti Graben.

Conclusion:

As we have seen, advertising is an industry guided by monetary demands. Yet it shapes people’s behaviors as consumers and as member of classes because of its setting of norms. We build our consumer identities partly in response to it. We have explored how marketing agencies are built and the different strategies they use to manage the transmission of their information to us depending on their needs and to which social class they are marketing their products for. We examined how companies tried to break the language barrier and how they attempted to cater to different linguistic communities. Sometimes they did so with great success through a localized understanding of the cultural and linguistic territory. Other times it was a great failure through standardized cold and lifeless, “one size fits all” procedures. Methods based on word for word translation to approach communities who sometimes feel invaded by a product they resent as out of place or as “not belonging” just work significantly less. We then focused on the case of Switzerland where it seems to us that companies have done a pitiful job of connecting with the rich multilingual potential of the multilingual country and transmit advertisements that feel out-of-touch with the perspective of many Swiss citizens. There is a lot left to learn on the subject and more research is needed. The studies we approached often noticed the lack of representation of certain communities on the global scene where the advertising they received was always very generic and sometimes not even translated. It is therefore difficult for us to learn about what is happening in those communities and we think in the future, as those markets develop and awareness of their presence on the global scene grows, inquiry on how global marketing will make its way, or perhaps fail to make its way, in a localized manner will be very interesting to look at.

AMOS, W. 2020. English in French Commercial Advertising: Simultaneity, bivalency, and language boundaries in Journal of Sociolinguistics, 24 (1), 55-74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12386

BOIVINEAU, R. 1972. Que pense-t-on de l’adaptation publicitaire en Belgique et en Suisse? In Meta, 17 (1), 47–51. DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/002098ar

EMOND, P. 1976. La traduction dans les agences de publicité in Meta, 21 (1), 81–86. DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/002708ar

FORUM, Le grand débat (vidéo) – Les pubs suisses sont-elles vraiment si nulles ? RTS Info, 11.12.2020, 18h31-18h50. Available at : Forum (vidéo) – Le grand débat (vidéo) – Les pubs suisses sont-elles vraiment si nulles? – Play RTS

GRIN, F., KORTH, B. 2005. On the reciprocal influence of language politics and language education: The case of English in Switzerland. Lang Policy 4, 67–85. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-004-6565-3

GUIDERE, M. 2009. De la traduction publicitaire à la communication multilingue in Meta, 54 (3), 417–430, p.420. DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/038306ar

MARTIN, E. 2011. Multilingualism and Web advertising: addressing French-speaking consumers in Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 32 (3), 265-284. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2011.560671

PILLER, I. 2001. Identity construction in multilingual advertising in Language in society, Vol.30 (2), p.153-186. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404501002019

Family language policies: how is the language transmitted through generation of immigrants ?

Aleksandra Jankovic, Tryphène Kileki

In this blog entry, we will discuss different possibilities of heritage language transmission, from the first generation to the second. We will especially concentrate on the factors on which language transmission depends and the parents’ motives for the transmission or non-transmission of the language.

Key words: family, bilingualism, generation, immigration

“3 generation family” by OURAWESOMEPLANET: PHILS #1 FOOD AND TRAVEL BLOG is licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

Introduction

As second-generation migrants we both have learned our heritage languages, but this is not the case for every migrant child. It depends on many factors, such as family relationships or parents’ effort, whether the child will learn the heritage language or not. Language has an important role for communication, understanding and relationships between different generations within a family. It is also important for identity. According to Spolsky (2012), the relationship that the second-generation migrants have with the heritage language is strongly linked with emotions and identity.

In this blog entry, we will discuss different possibilities of heritage language transmission, from the first generation to the second. We will especially concentrate on the factors, on which the language transmission depends and the parents’ motives for the transmission or non-transmission of the language. For this purpose, we will explore various types of family language policy in the UK.

Wilson (2020) reports that, according to the latest report of the office for National Statistics, 34% of the children born in the UK have at least one parent from another country, which means that many children are in contact with another language other than English at home. This does not mean that they do not know English, quite the contrary. According to Bloch and Hirsch (2017), in the UK, 92.3% of the national population speak English as their main language. Only 0.3% of the national population do not speak English at all. However, Bloch and Hirsch (2017) assert that the political discourse of the state about language plays a negative role in the heritage language transmission. They add that politicians promote “integrationism” that forces people to learn English in order to gain citizenship. Foreign languages are negatively portrayed by the government and are linked to the image of the “outsider”. Spolsky also highlights that “state-controlled education commonly sets up a conflict between heritage languages and the national standard language” (2012: 4).

Generalities and basic information

Before getting to the heart of the matter, certain concepts need to be clarified in order to avoid confusion.

- Heritage languages (HL) are “ethnic minority languages”. They are spoken within a migrant community in a foreign country, where another dominant language is spoken. (Montrul 2011).

- By native language, we mean the language that the parents spoke in the foreign country before coming to the UK.

- First generation migrants are people who were born in a foreign country and then came to the UK. People from this generation master their native language. Some of them can also speak English.

- Second generation migrants are children who were born in the UK, from parents that come from another country. They “present the most variability in bilingual ability.” (Montrul 2011). They are also the most analyzed group.

- Language shift happens when a community starts to replace their own native language with another language.

- Family language policy (FLP) is when a family explicitly plans which language they will use between the family members.

Many studies about the transmission of the heritage language in migrant families in the UK were conducted. For our review, we will be focusing on six research papers. All these studies assert that the acquisition of the heritage language happens mainly at home, within the family. Children learn the language from their parents. Thus, migrant parents play a significant role in the transmission of their native language to their children, who were born in the UK. Miekisz, Haman, Łuniewska, Kuś, O’Toole & Katsos (2017) argue that the exposure of children to a bilingual environment (e.g bilingual day care setting) can also have a positive impact. But not every migrant child acquires their parents’ native language, and some of them can only speak English. It can also happen that children understand the family heritage language but cannot speak it or cannot speak it fluently. Another possible outcome of FLP are the bilingual second-generation migrants, who understand and can speak their HL fluently as well as English as the dominant language.. Some people learn the heritage language when they are children but once they grow up and do not live with their parents anymore, they tend to forget their language and speak English only. A lot of variations in the acquisition of the heritage language by the second generation are possible; all the studies agree on this point. There are no universal patterns, as it changes from family to family : hence the importance of FLP as a new field of research.

The studies that we selected are trying to find out and understand the factors that play a role in the transmission of the heritage language and also to grasp the parent’s motives for the transmission or non-transmission of the language. Several factors can impact the transmission of the language and they vary from one family to another. We will attempt to provide some examples from the six articles in order to explain the impact of different factors on the acquisition of the heritage language. These factors can be linked to personal factors like the family situation (divorced parents, contact with other members of the family), national identity (how the speaker perceives him- or herself), to integration or even to discrimination (fear of being different). But politics can also play a role in the acquisition of the heritage language (e.g. speaking Kurdish in Turkey is forbidden, so when people emigrate, they tend not to speak this language to their children).

Literature review

According to Canagarajah’s study (2008), the Sri Lankan Tamil migrants experienced a language shift toward English and they tend to lose their native language more than other migrant communities. He interviewed different Tamil families from Sri Lanka in order to understand their behavior concerning language transmission and the reasons for the lack of transmission of the Tamil language. He found out that the reasons are not the same in every family. But he argues that English colonialism has played a significant role in the loss of the Tamil language within migrant families. English was introduced in Sri Lanka around 1780 by British colonizers and it has been perceived as a superior language since then. He explains that, in Sri Lanka, people see English as a prestigious language. They think that it is very important to learn English. People who do not know English think that they will be considered as ignorants and simple-minded. Canagarajah explains that, as a consequence, when Tamil people come to the UK (or another English speaking country), they are so preoccupied with learning English that they tend to neglect their native language. The parents’ fluency in English can also impact the transmission of the language in different ways. Canagarajah explains that some Tamil parents who do not speak English rely on their children’s help for interactions outside the home (e.g for administration). They also count on their children to teach them English and most of them learn English via their children. For these reasons, parents tend to encourage their children to learn and use the English language more than their heritage language. This can lead to a loss or a non-acquisition of the heritage language by the children. However, it is also possible that parents that lack fluency in English talk with their children in their native language only, consequently the child will acquire the heritage language and will be fluent in it. Among migrants in the UK, there are also refugees, who had to flee their home country. Bloch and Hirsch (2017) have interviewed second generation migrants, whose parents have fled their home country. They attempted to analyse how and whether the transmission from the first to the second generation happens and they also analyse the context in which it happens. They have found out that most of the second generation refugees children have indeed acquired proficiency in their heritage language. However, Bloch and Hirsch have noticed that the use of the heritage language was limited to the home and the family context.

They argue that “politics of language use and the policies that exclude languages other than English create an environment where heritage languages are not valued” (Blosch and Hirsch 2016). A Sri Lankan Tamil person interviewed in this study explained that when she was with her classmates and her mother called her on the phone, she used to reply in English, even if her mother talked in Tamil. She justifies this by saying that she did not want to be different from her classmates.

Blosch and Hirsch explain that other participants also felt that way and that they sometimes experienced racism from their classmates. But they also assert that this is because children assimilated school policies about language. They give the example of a girl who spoke only Tamil when she started school. Her teacher was worried about this and she advised the girl’s parents to speak English only at home, in order to improve her English. Consequently, the parents decided to also speak in English with their younger children. Furthermore, two Kurdish girls explain that, when they spoke Kurdish in their classroom, their teacher forced them to only speak English.

The case of French second-generation migrants in the UK differs from the others because of several reasons. The principal reason is the high prestige of the language in the UK. As a matter of fact, French is part of the British curriculum, which means that the second-generation migrants have an advantage in speaking French at home. In Wilson’s study (2020), a group of children from three families were interviewed to understand the FLP through their eyes. It is true that the parent’s choice about what language they will talk to their children has a great impact, but there is not a lot of research taking into account what the children feel about it and how they perceive that language policy in action Wilson’s case studies are children that have one french parent and one British one and the three families have different FLP in regards to the HL (French).

In the first family (A), the children (9 and 16 years old) “use English exclusively with their father, whereas French is the only language of interaction with their mother, in all circumstances” (Wilson, 2020). This is due to the french mother’s strict language policy, ignoring her children when they are addressing her in English. The reason behind such a strong insistence on her children speaking French is said to help them be more proficient. The effect of this FLP on the children is that they both define themselves as half English and half French. However, the girl expressed resentment towards her mother who ignores her when she speaks in English, when the big brother is more resigned. Overall they say they are grateful to be able to connect with their French relatives.

DOI: https://doi.10.1080/01434632.2019.1595633

In the second family (B), the French mother translanguages often but addresses her children (11 and 13 years old) mostly in French. She “qualifies her approach to the transmission of the minority language as ‘relaxed’” (Wilson, 2020). She is conscious that her children’s French could be better but also that they have an advantage in school because of their level in French. The attitude of the children towards the language is not the same even if they had the same education.

Her brother sees himself as English, on the contrary. Both siblings recognize their lack of skills in French but the sister has taken the initiative of improving her French whereas her brother does not do the same

The third family (C) have a strict French-only policy. It means that in their home and outside, the family only communicate in French. The father is French and the mother has a really high level in French. The application of the only-French rule makes the parents (especially the father) have a “immediate and systematic” (Wilson, 2020) negative response whenever the children (6 and 4 years old) speak in English or mix it with French. Wilson argues that this leads to a problem of communication since the children are stopped in their attempt to say something. In other words, the strong reaction of the parents makes the form of what the child is saying more important than the content. The children in this family are still young but the older brother already said that he will not speak to his children in French because “it takes too much time” in his words. He also expresses negative feelings related to the ignorance of his father when he tries to speak in English.

In conclusion, this study has revealed the feelings that the children have during the moment the FLP that their parents choose is in action. The feelings are mixed and often differ between the children of the same family. The future of the French into the children’s lives is not known yet, but there is already a tendency that can predict whether or not they will keep speaking in French.

Conclusion

In order to conclude, we can say that this is not possible to make certain predictions about language transmission. According to Wilson “different FLPs may produce similar results, while similar language management methods may lead to different reactions among children” (2020). What can be seen are tendencies about how the different language policies that the parents decide to have in their home will affect their children. There are a multitude of factors that determine if at the end of the day the second-generation migrants will have the relationship with the Heritage Language that the parents wanted them to have. One of the major factors is that all humans are different and even in the same home the reactions can be different.

As second-generation migrants, we did not feel any particular pressure to speak French only, in our environment (French-speaking Switzerland). There is no shame about speaking another language. Thus, we can say that our environment is maybe more “multilingual friendly” than the UK. In addition to all the factors linked to the family, politics also can impact the transmission of the language. It would be interesting to compare the swiss and the british political environment and to compare the impact that they have on the transmission of the heritage language in migrant families in future studies.

Bibliography

Bloch, A. and S. Hirsch. 2017. “Second generation” refugees and multilingualism: identity, race and language transmission. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40 (14). pp. 2444-2462. Available at: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/623131/3/Bloch_and_Hirsch_ERS_2016_author_accepted_.pdf Accessed on: 15/12/2020

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. 2008. Language Shift and the Family: Questions from the Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora. Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 143–176. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2008.00361.x Accessed on: 15/12/2020

Montrul, S. (2011) INTRODUCTION: The Linguistic Competence of Heritage Speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33, no. 2: 155-61. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/44485999. Accessed on: 23/12/2020

Miękisz A., E. Haman, M. Łuniewska, K. Kuś, C. O’Toole & N. Katsos. 2017. The impact of a first-generation immigrant environment on the heritage language: productive vocabularies of Polish toddlers living in the UK and Ireland, International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20:2, 183-200, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1179259. Accessed on: 15/12/2020

Spolsky, B. 2012. Family Language Policy – the Critical Domain. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 3–11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2011.638072 Accessed on: 15/12/2020

Wilson S. 2020. Family language policy through the eyes of bilingual children: the case of French heritage speakers in the UK, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 41:2, 121-139, DOI: https://doi.10.1080/01434632.2019.1595633. Accessed on: 15/12/2020

Multilingualism in Swiss advertisements: where Swiss chocolate meets English tea

By Ludovick Flachat and Asia Thommen

Short description: In this blog entry, we investigate the reasons behind and the locations in which the swiss advertisement industry employs English as a lingua franca.

Keywords: Multilingualism, Advertisement, Switzerland, English, Lingua Franca.

Introduction

Multilingualism is one of the most typical characteristics of Switzerland. According to Patricia Ronan (2016), since 1938, there are four national official languages in the country: German, French, Italian and Romansh. Although its linguistic variety is one of Switzerland’s key characteristic, it remains one of the main issues within the country. Indeed, managing these languages is not an easy task even if the territoriality principle is in place, making each canton responsible for the designation of an official language. Therefore, out of the 26 cantons, 17 have German as their official language, 4 have designated French only and 1 opted for Italian. There are also 3 German and French bilingual cantons (Bern, Valais and Fribourg) and 1 German, Italian and Romansh trilingual canton (Graubünden).

Nevertheless, it is still hard for every Swiss resident to understand and be understood everywhere in the federation. Furthermore, it raises the question of which language(s) to teach the younger generations. Consequently, English as a lingua franca is used as an answer to fill the gaps. Its use in Switzerland kept on increasing from post-World War II onwards, becoming the main language of 4.4% of the Swiss population (Ronan, 2016: 16). English as a lingua franca is especially used in work environments such as the army, universities or advertising. The language is thus considered as neither a second nor a foreign language, but its status lies somewhere in between (Cheshire, 1994). Hence, it is expected that English is also used in Swiss advertisements.

In this blog entry, we will investigate the use of English in Swiss advertising based on academic papers and Swiss ads that we collected on the internet (Autumn 2020). We will apply the theories in the literature to our country’s advertising system, exploring why Swiss-based companies use English for its advertising and in what ways it is doing so. In particular, we will study phenomena such as “language contact” which consists of the interaction of two or more languages found in the same material, leading to a transfer of linguistic features and style.

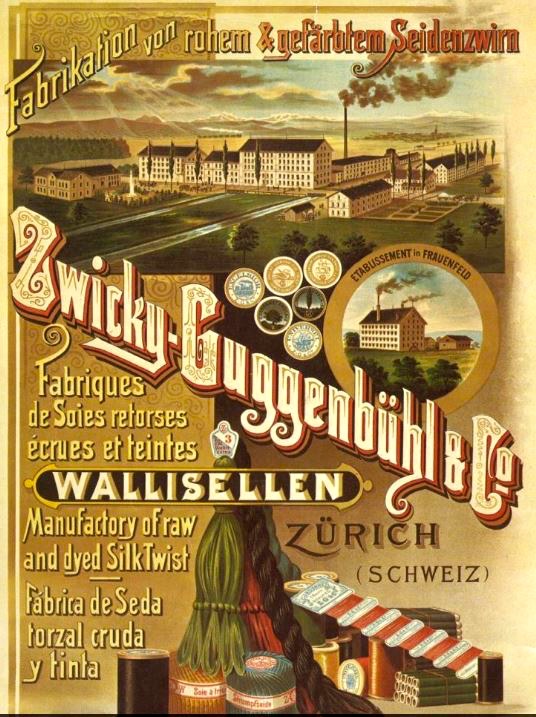

The one above is an obvious case of language contact in Switzerland. We chose this example of advertisement because it illustrates perfectly the complexity induced by the Swiss’ spectrum of languages. The manufactory is based in Zurich, in the Swiss German part of Switzerland, which explains why the main title is in German. However, it is translated in three other languages. One of them is French, another official idiom of Switzerland. The other two are Spanish and English, two of the most spoken languages in the world. This choice was probably made in order to expand the audience of the advertisement to a more international level.

The first part of the blog entry will provide some theoretical context in order to explain why English is part of Swiss society and therefore the advertising system. In the following section we will highlight how the language is used in Swiss advertisement and the fundamental reasons for the choice of English in the Swiss advertisement system by also giving some examples. Finally, we will conclude our blog entry by illustrating the limitations and the possible further directions for research.

Theoretical Framework

The advertising world is in a continual expansion, becoming more influential and thus receiving an increasing budget. This development hence induces a modification of its codes and values such as the birth of “super brands” (Piller 2003: 176) in the 1990s. Super brands are trademarks that take their value from their symbolic charge created by the ways in which they are advertised more than the product itself or the service they provide. Brands such as Nike or Calvin Klein play with these codes and the “conceptual value-added”. The value added is the additional feature or economic value which a company adds to their product before offering it to the customers. In order to make their brand successful internationally thanks to globalization, advertisers have created a “brand pidgin” (Piller, 2003: 176) which consists of logos and the use of slogans. These tools lead to a global understanding and recognition of one’s brand.

Interestingly, one way of doing so is by language contact, which increases the use of English in non-English-speaking countries. Moreover, English is globally considered as the language of modernization and technology (Piller, 2003: 175). Its spread is facilitated by the extensive use of the language in global communications (80% of the total), but also by the internet marketing. Switzerland is also affected by this phenomenon in many ways, including the use of English as a marketing strategy. In fact, the Swiss population, being multilingual, often uses English as a foreign language. This implies that Switzerland is a part of Kachru’s “expanding circles”. Kachru’s model defines three different categories of users of English (Bhatia, 2012: 571). First, the “inner circle” (UK, USA etc.) which is composed of the countries that have English as L1 and created the norms which then spread to the other circles. The second is the “outer circle” (Singapore, India etc.) thus the circle of people who learned English as a second language because of their background as an English colony. At last, the “expanding circle”, which consists of most English speakers worldwide, in which English does not have a governmental status but is generally studied as a foreign language. It is a circle which is dependent on the norms created by the Inner circle. Most of swiss speakers learn English as a foreign language which makes them a part of the last group.

As we have seen before, multilingualism in Switzerland is its strength in terms of tourism trade and international relations, but also a debate within the country. Though it is true that in Switzerland, English could be seen as a foreign language, it is also often used to fill the lack of knowledge of the other official languages, thus accepting the role of an internal lingua franca. Cheshire even defines it as a “‘neutral’ second language for all the Swiss language groups” (1994: 453). English can thus be considered as a lingua franca that can be the bridge between all parts of Switzerland without favouring one of the four official languages.

Previous studies and examples

In her research, Ingrid Piller discusses the use of English in advertising, comparing it to the use of other foreign languages. Usually, the use of an additional language, different from the national language, is related to ethno-cultural stereotypes as it is the case of English within British class in continental Europe. However, as Piller underlines, in the case of English, focusing on the ethno-cultural stereotypes is irrelevant considering its overuse in many areas. Thereby, English is more associated with social stereotypes such as prestige, modernity or progress. As we can see in the next few examples, the use of English in advertising is happening alongside the three Swiss official languages (German, French and Italian). In our blog we decided not to include an example of the Romansh-English contact as the language is dying and finding a multilingual advertisement would be too difficult.

As this first example highlights, English is used to emphasize the prestige of this Swiss luxurious watch. This is a Swiss ad on the Rolex’s website. The website chosen is mainly in French, but as you can see the marketing team decided to name the product with an English name: “sky-dweller”. English product naming is the most favourite and easily accessible process in multilingual advertising (Bhatia, 2012: 579). Additionally, it often happens that a product’s name and advertisement are an expression of the company’s origins. For instance, Coca Cola is an American brand which has decided to keep their slogan “taste the feeling” in English in all countries including Switzerland. Bhatia (2012: 580) also explains that English can occur in many structural domains such as slogan and product name but also company name or logo, labelling and packaging, pricing, main body, headers and sub headers.

Accessed on: 12/12/2020.

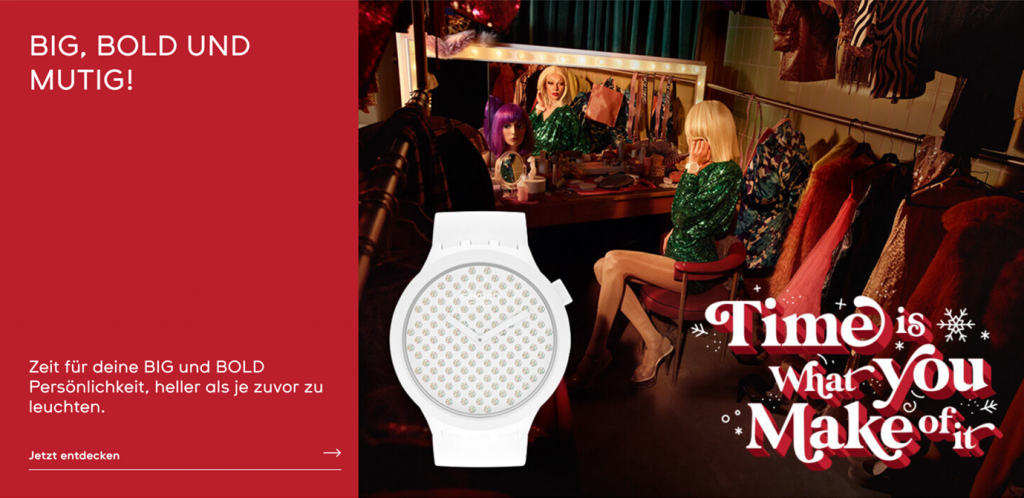

In this second example above (see Figure 3), we can see an ad from the Swiss company “Swatch”, which sells watches and bracelets. Here the advertisement on their website is in German but uses English to name their product (BIG BOLD) but also for their slogan: “Time is what you make of it”. The website is also available in French, where the slogan still includes English. English slogans usually are sentence-like and not just one-word structures and the Swatch’s ad is a perfect example. As for the example of the Rolex watch, this is another case of English product naming, considered as the simplest process in multilingual advertising (Bhatia, 2012: 579).

In this third example we can see that the description of the website, thus the main body, is in Italian, but the header is in English. This is probably done in order to reach a wider audience, and to suggest to the reader that the page can be translated to other languages. Moreover, as in the Rolex watch advertisement, English could be used to emphasize the luxury and modernity of the brand. As for the last examples, English is thus used to exalt the level of internationality and modernity of the product in order to attract the receiver of the advertisement to buy the Swiss product.

The three given examples are from swiss brands on their swiss websites in the three official languages. It is interesting to notice that this phenomenon appears in all of the three official languages of Switzerland. Indeed, one language could be more likely to use English. For instance, we suppose that a minority language such as Italian could perhaps increase the use of English in the publicity world or even in the canton altogether, in order to make sure that the advertisements and information are understandable by all Swiss visitors. Ultimately, all parts of Switzerland use English in their marketing strategies.

As we saw with these examples, English is an extensively used language within Switzerland, and it does not seem like it is only used to show a level of internationality which could attract tourists, but also for other interesting reasons. In 1994, Jenny Cheshire wrote an interesting paper in which she talks about advertisements in Switzerland. The year of this article could be seen as a complication, but we consider that her conclusions are still relevant for the case of Swiss advertisement nowadays.

Firstly, she states that the use of English in Swiss ads could be seen as a convenience for the advertiser who can use the same commercial in the four different linguistic regions without having to change its text. Secondly, Cheshire develops an intriguing point on how the Swiss use English as “a way of transcending a problematic national identity, in order to allow them (the Swiss) to construct a self-image that is consistent with the favourable image that they present to tourists” (Cheshire, 467). Swiss advertisers thus use(d) English in their ads in order to connect with international tourists and construct a more favourable image of the land for travellers coming from all over the world. Finally, a more practical point must be considered. Switzerland has a total number of four national languages and at least eight different German-speaking dialects (varieties of Schwytzerdüsch). Therefore, we could say that there is not one single language that could serve as a national symbol of the Swiss identity. Furthermore, three of the four official languages are also the languages of the neighbouring countries, an aspect which diminishes the concept of Swiss national language.

What we still consider as a controversy is whether, from a more ethical point of view, it is in Switzerland’s best interests to use a foreign language and not one of its own national languages. Maybe using more multilingual advertisement in the four official languages would encourage Swiss residents to learn or at least remember some of the other Swiss languages. In fact, Swiss pupils have to learn a second national language at an early stage of life. This reveals the importance for the swiss residents to learn other national languages, in order to have broader work and educational opportunities. Nevertheless, a study led by the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education[1] revealed that only twelve of the twenty-six Swiss cantons learn a second national language before learning English. The fourteen remaining cantons provide an English education before the second national language. What is interesting to notice is that the fourteen cantons in which English is taught before a second national language are mainly the Swiss-German cantons: Uri, Obwalden, Nidwalden, Lucerne, Zug, Schwyz, Glarus, St. Gallen, Aargau, Appenzell Innerrhoden, Zurich, Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Thurgau and Schaffhausen. In fact, the matter of language education is a regional decision. But the fact that for the Swiss German region it is more important to learn English very early in the education implies that English is used more than in the Swiss French or Swiss Italian region. This hypothesis is confirmed by a study lead by the federal office of statistics (De Flaugergues, 2016), in which it is established that generally the English language is used more in the Swiss German regions than in the other Swiss regions.

Conclusion

The case of Switzerland is thus very interesting in terms of multilingualism. It already has four national languages of its own, but as we can see from the examples of advertising above, English is often used as a solution to reach the most extensive audience possible. It must be kept in mind that it is the federation of Switzerland which is multilingual, not the population. This means that not all of the Swiss residents are able to communicate in a national language, i.e. without using a lingua franca to understand each other (which in most cases is English). The issue of communication can also be found in the context of advertisement, a reason why English might be so extensively used in the world of publicity. As said before, another reason for using English is because it is considered as the language of modernization and technology (Piller, 2003: 175), characteristics which can help the selling of a product. Finally, as Cheshire (1994) states, the reasons which lead Switzerland to use English in the advertising system are multiple and can be summarized in three main points. The convenience for the advertiser who does not have to translate the announcement for different linguistic regions, the creation of an alternative and tourist-friendly identity and finally a more practical point, the fact that Switzerland cannot be represented by a single language. Considering all of these issues we personally find that the use of English in Swiss advertisement can be considered comprehensible. Because of the multilingual peculiarity of Switzerland, English provides a fundamental contribution to the comprehension of advertisements and we perceive the use of the language as a necessity.

According to what we have learned with this research we would find it interesting to consider the case of English in more official matters as in the communication from the Swiss government. This would allow us to comprehend the importance and the policies used while managing English as a lingua franca in a country which is already multilingual.

Definition of concepts

Foreign languages: language which is not indigenous and used as a vernacular in a given country.

Lingua franca: language used in order to communicate between two individuals which do not share the same native language.

Monolingual: when the language repertoire of an individual or an entity is composed of only one language

Multilingualism: when the language repertoire of an individual or an entity is composed of more than one language.

Multilingual advertisement: advertisement which uses more than one language.

Official language(s): usually the language (or languages) used by the government, hence the language(s) which has a legal status in a particular country/territory.

References

Bhatia, T. K., and W.C. Ritchie. 2012. Bilingualism and Multilingualism in the Global Media and Advertising. In T. K. Bhatia and W. C. Ritchie (ed.), The Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism. Blackwell Publishing, 563–597.

Cheshire, J. 1994. English as a Cultural Symbol: English as a Cultural Symbol: The Case of Advertisement in French-Speaking Switzerland. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 15.6, 450-469.

De Flaugergues, A. 2016. Pratiche linguistiche in Svizzera : Primi risultati dell’Indagine sulla lingua, la religione e la cultura 2014. Statistica della Svizzera. Available at: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/it/home/statistiche/cataloghi-banche-dati.assetdetail.1000181.html. Accessed on: 22.12.2020

Demont-Heinrich, C. 2005. Language and National Identity in the Era of Globalization: The Case of English in Switzerland. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 29.1, 66–84.

Piller, I. 2001. Identity constructions in multilingual advertising. Language in Society, 30.2, 153–186.

Piller, I. 2003. Advertising in a Site of Language Contact. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 23, 170-183.

Ronan, P. 2016. Perspectives on English in Switzerland. Cahiers de l‘ILSL 48, 9-26.

Vettorel, P. and V. Franceschi. 2019. English and other languages in Italian advertising. World Englishes, 38.3, 417‑434.

Images:

Figure 1: Arnold Zwicky’s blog. 2021. A Swiss thread. Arnold Zwicky, twenty-fourth of January. Available at: https://arnoldzwicky.org/2018/06/19/a-swiss-thread/. Accessed on: 24/01/2021.

Figure 2: Rolex. 2020. Home page Sky-Dweller Presentation. Rolex, Twelfth of December. Available at: https://www.rolex.com/fr. Accessed on: 12/12/2020.

Figure 3: Swatch. 2020. Swatch Home Page Big Bold Presentation. Swatch, Twelfth of December. Available at: https://www.swatch.com/de-ch/homepage?gclid=CjwKCAiAlNf-BRB_EiwA2osbxdP87GBAl87WGj8TH_GlEaHooryf04dHxpjepQDJdZNDM-bDLlqTKRoCCTIQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds. Accessed on: 12/12/2020.

Figure 4: Lindt. 2020. Home page Lindt. Swatch, Thirteenth of December. Available at: https://www.lindt.it/. Accessed on: 13/12/2020.

Quadrilingual Switzerland – a model for multilingual education?

Marine Fiora, Katharina Schwarck

Content

In this blog post, we will investigate multilingual education in the plurilingual country of Switzerland, what its policies and programmes are, and how and why they are implemented.

Keywords: bilingual education, Switzerland, territoriality, monolingual ideology, multilingualism

Figure 1: Ⓒ Ben White

Switzerland is officially a quadrilingual country (Meune 2010) where the national languages are German, French, Italian and Romansh although many other minority languages are spoken as is the case with English, which is becoming increasingly important. Since Switzerland is a federation, the sovereign cantons define their official language (Paternostro 2016; Zimmermann 2019), according to the main language spoken by their inhabitants: this is called the principle of territoriality. It is customary to have only one official language in each different region. Switzerland is therefore, rather than a quadrilingual country, a mosaic of monolingual regions where the principle of territoriality creates a well-defined separation between the languages (Grin and Schwob 2002). The language borders are visible in the Figure 2 illustrates. However, the majority of Swiss people are far from quadrilingual. The notion of language borders is important for the understanding of the topic of multilingual education because it highlights the difference between societal bilingualism and personal bilingualism. Indeed, a country can be bilingual while the citizens are not necessarily (Grin and Schwob 2002). Of the 26 Swiss cantons, only three are officially bilingual (i.e. Valais/Wallis, Fribourg/Freiburg, Berne/Bern) and only one is trilingual (i.e. Graubünden/Grigioni/Grischun) (Grin and Schwob 2002). In order to improve understanding between language areas, it is obligatory for children to be taught a second national language at school. It is necessary to understand the language policies and their implementation in different cantons in order to maintain national cohesion in the country.

Figure 2: “Map Languages CH” © Marco Zanoli. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Multilingualism is a language ability which includes the use of several languages in our repertoires. However, in our current neo-liberal period, this faculty can be a great asset, whether cultural or economic. Having multiple language repertoires gives access to prestige languages and facilitates communication between people with different mother tongues. Moreover, with English becoming even more important and global throughout the years, learning it as foreign language has become increasingly common and almost required in order to use it as a lingua franca.

One way of learning a foreign language is bilingual education. As García (2009) explains, bilingual education is a mode of education in which the language studied is used as a means of communication and not as the target of study as is the case in traditional language classes. The aim of this approach is to immerse students in a different culture, language and way of thinking, enabling them to obtain intercultural skills. This method is called immersion teaching and has been practised all over the world since the 1960s to varying degrees. According to Lys and Gieruc (2005), the first study experiment of this type of teaching was conducted in bilingual Canada, where parents of English-speaking students had demanded a more effective type of French teaching, in order to improve their children’s socio-economic chances. Following this demand, an experimental programme was set up to verify the effectiveness of this type of learning. During these first immersion experiences, parents were concerned that learning another language could have cognitive repercussions on their children. The results of this evaluation were very positive and led Canadian political authorities to promote this type of teaching throughout the country. Shortly after Canada, many other countries moved to develop education in foreign languages, as for instance countries in Europe. This type of language teaching seems to be becoming more widespread in order to develop students’ socio-economic chances and intercultural communication (Lys and Gieruc 2005). Another way of learning a foreign language is Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) which allows the learning of a language in non-linguistic focused courses. This means that some classes will be taught in the target language without being a grammar or vocabulary course. When not all classes are taught in the target language, but also in the pupils’ regional language, this structure is also called a dual immersion programme.

These modes of learning can be particularly useful and interesting in a multilingual country like Switzerland, where federalism allows Swiss cantons to choose their school curricula and how they approach language learning (Grin and Schwob 2002). In fact, Switzerland has always worked with the goal to promote the cohesion of its cantons. From the 1970s onwards, the study of a second national language in primary school was added to the study of the pupils’ native language (Paternostro, 2016). This raises the question of the implementation of bi/multilingual education in public schools in the Swiss cantons and the differences between them.

The Swiss Federation has been accepting several kinds of bilingual school courses since 1995 (Elmiger 2008), allowing the cantons to build up their own programme and promoting exchanges between the different language areas (Meune 2010). One notices that in regions of contact between two languages, bilingual programmes develop more naturally, and there are more possibilities for educating children which take into account their particular language situation when they are, for example, speakers of a national minority language. Evidently, measures and programmes are not restricted to native speakers of a national language, but do also extend to students’ whose parents’ might be migrants and whose home language might not be official Swiss. In officially monolingual regions the creation of a bilingual programme depends on the school and it aims to improve students’ skills and socio-economic chances (Elmiger 2008). Nevertheless, not all cantons have regulations on the design of bilingual courses in the secondary level, especially in smaller cantons or in those where only one or a few schools offer a bilingual curriculum. Where these programmes do exist, they are not always equally detailed.

In 2008, the cantons of Geneva and Zurich – the biggest and most international cantons – Berne/Bern and Fribourg/Freiburg, and monolingual Aargau and Vaud had developed detailed specifications for their bilingual programmes, often in order to promote them (Elmiger 2008). Typically, bilingual programmes exist sporadically in German-speaking Switzerland while in Vaud’s gymnases (the Swiss equivalent of High School), in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, such programmes are available to everybody in state schools. The bilingual programmes usually last three or four years and begin in the ninth or tenth year (ages 14 to 16) in the German-speaking part and in the tenth or eleventh year (15 to 17) in the French-speaking part (Elmiger 2008). Most programmes are based on high school students (ages 15 to 19) taking part in classes in the immersion language at their home school and a host school, where the target language is spoken (at least 600 classes in total for the whole programme). In other schools the immersion only takes place in a host school of the target language. According to Elmiger (2008), in 2008, about 10% of all Gymnasium/gymnase students in Switzerland completed a bilingual school course, 40% of all Gymnasien/gymnases offered bilingual education, and the number has not stopped growing since. The most frequently taught immersive subjects are History and Mathematics although the range of subjects found in the individual programmes is very broad (Elmiger 2008). The most immersive teaching takes place during the penultimate or the last year before the Matura or maturité. The total number of bilingual lessons varies: while some schools seem to teach fewer than the 600 periods prescribed by the canton, others even exceed the target substantially as some schools plan up to 1400 immersion lessons (Elmiger 2008). Since Switzerland’s cantons are sovereign regarding school policies, the decision regarding bilingual education is different in each of them.

To illustrate this, the French-speakers in Berne/Bern are a minority and are traditionally present in the Jura bernois. Meune (2010) shows a major distinction in this canton compared to the others. Indeed, the Bernese Constitution precisely associates either German or French with a given district based on territoriality. In the exceptional case of Bienne/Biel, every inhabitant can choose their own administrative language as well as the main language taught at school.

Meune (2010) highlights that in the city of Fribourg, the two languages are co-official but that it is very complicated to have a perfect balance between them at all levels. Fribourg is a French speaking town with a minority of German speakers who are entitled to administrative services and schooling in German. Moreover, the canton of Fribourg/Freiburg offers bilingual courses in its university and in several of its schools of tertiary education. The University of Fribourg, for instance, is fully bilingual and allows students to take courses in Fribourg as well as at the monolingual universities of Neuchâtel (Francophone) and Bern (Germanophone), allowing all curricula to be bilingual. The Fribourg School of education, for its part, provides administration and teaching in both German and French and encourages second language immersion for students, with the idea that all future teachers should have bilingual skills.

Figure 3: Sign at Fribourg/Freiburg Train Station “Quelque chose a changé, en notre…” © centvues. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Valais/Wallis was the first canton to declare itself bilingual, but it offers a much clearer linguistic separation than Berne/Bern and Fribourg/Freiburg (Meune 2010). In their study, Grin and Schwob (2002) compared two Valaisan/Walliser CLIL programmes: one which began in kindergarten and another that began in third grade. In both examples, part of the classes were given in the target language by a native speaker. The programmes have shown that pupils in their fourth year of primary school who have followed the bilingual path from kindergarten onwards had almost the same understanding in the target language as native speakers (10-20 percentage points less). They also highlight that bilingual education does not only give better results from the students but also much more enthusiasm towards foreign language acquisition (20% more satisfaction). The canton also offers the opportunity for each municipality to create a bilingual structure under certain conditions (Canton du Valais 2006). At Gymnasium/gymnase level – called collège and Kollegium respectively in Valais/Wallis – the canton offers bilingual German-French education in the Kollegium/collège of Brig and Sion, a bilingual English-French education in the collège of Saint-Maurice and a German-English education in the Kollegium of Brig. In this way, we can also observe an emergence of the importance of English, both in the German and on the French-speaking part. Furthermore, the school of education has two sites, one francophone, one germanophone. There, students start their studies in their native language but over the course of their diploma need to spend at least two semesters immersed in the other language on the other site (Brohy 2008).

Ticino is the only Italian-speaking canton in Switzerland. This canton has the particularity of making the learning of two other national languages at school as well as English compulsory. Since a change of policy where the students can choose the languages which they want to learn and French passes from compulsory to optional in upper secondary, we notice a decrease in the learning of French (-12% less students) (Paternostro, 2016). This can be explained by the prevalence of German in Switzerland. Indeed, many people in Ticino believe that German must be acquired in order to have a secure future (Zimmermann 2019).

The trilingual canton of Graubünden/Grigioni/Grischun – in which inhabitants speak German, Italian, and Romansh – highly promotes the two minority languages, Italian and Romansh, in order to keep them alive. Therefore, Italian- or Romansh-speaking students are encouraged in their use of their native language at school and the presence of these languages in schools is reinforced. The canton also offers courses partly in the students’ native languages, partly in a second national language, as well as it offers immersive phases for both.

In the year 2000, the monolingual canton of Vaud introduced le modèle mixte – the mixed model – of their maturité bilingue. This consists not only in a first year of schooling in a regular class, with pre-registration for a maturité bilingue but also in a period of language exchange in a German-speaking region. During this period, the students follow the classes of a host gymnase for either 10 to 12 weeks at the end of their first year, or for the entirety of their second year. Then the student is required to be part of a bilingual class in the second or third year, where subjects such as Mathematics and History are taught in German, if possible. Students also attend regular German classes. Following the introduction of this programme, various financial and organisational support measures were taken to help students and families. The greatest problem, however, was finding instructors who have the right qualification to teach a subject in German. (Lys and Gieruc 2005)

In Elmiger’s (2008) survey, the schools were asked why they offer a bilingual Matura course and the most important reason for bilingual high school education was parent or student demand, which is particularly high in bilingual cities, but also in German- and French-speaking Switzerland. The second important point was the opportunity for the school to distinguish itself through a bilingual education programme. This second reason is much more visible in the Gymnasien in German-speaking Switzerland while in the gymnases in French-speaking Switzerland this is far less the case (Elmiger 2008).

Thus, bi- and multilingual education is more widespread at secondary levels (Elmiger 2006) even though there are also bilingual curricula at kindergarten and primary school level, which are more common in private schools (Grin and Schwob 2002); in primary schools, some subjects are taught in the target language (Elmiger 2006). However, schools often depend on the availability of suitable teachers. Counterintuitively, bilingual cities present a great shortage in suitable teaching staff. Elmiger (2008) presumes that this reflects the strict cantonal requirements for teachers in order to allow the highest quality of teaching. Indeed, the teachers must have a university degree in the target language or equivalent (Grin and Schwob, 2002).

Meune (2010) examined the individual bilingualism of the officially bilingual cantons and found the following percentages: 39.2% of the French-speaking inhabitants of Fribourg/Freiburg consider themselves bilingual compared to 72.9% of the German-speaking citizens. In the canton of Bern, this percentage is similar in proportions: 58.8% of German-speakers are bilingual compared to 52.1% of French-speakers. The bilingual canton with the lowest percentage of bilingualism is the canton of Valais/Wallis: 21% for French-speakers and 42.6% for German-speakers. This low percentage among the Valaisans/Walliser can be explained by a much clearer language boundary. In fact, the famous Röstigraben divides the canton into two very distinct parts and the semi-cantons function as juxtaposing parts (Meune 2010).

This blog investigates the provision of bilingual education in Switzerland by comparing the demographic differences between the cantons and their school curricula. It can therefore be asserted that Switzerland, although multilingual, has a monolingual ideology (Zimmermann 2019; Zimmermann and Häfliger 2019). The majority of regions have one official language and the majority of Swiss speakers are fluent in only one national language. Cantons are sovereign regarding their education policies, supporting their creation of school curricula according to their needs. Nevertheless, cantons’ sovereignty also implies that some can make less effort to make the population multilingual. Globally, bilingual education has a growing demand, as parents and pupils believe it to grow one’s socio-economic chances. The schools also use it to differentiate themselves and the biggest impediment to bilingual classes is teachers’ availability. Most bilingual education in Switzerland consists of an immersion period in a different linguistic territory and content courses in the target language in the home school at Gymnasium/gymnase. However, universities as well as other schools at a tertiary level offer bilingual curricula, either through agreements with other universities, or exchange programmes with other associated sites, especially for teacher trainees. The results of bilingual education are outstanding: not only do the pupils achieve better academic outcomes, but they also manifest more enthusiasm for education overall.

Can Switzerland be considered as a model for multilingual education? Switzerland has the difficulty of needing to handle several languages while also having to ensure that linguistic minorities speaking a national or a migrant language are represented. Furthermore, the principle of territoriality can be both a disadvantage, because it does not allow language mixing easily, and a strength, as it gives way to cantonal freedom to shape schooling according to the population’s needs and differences. If education policies were federal and “one-size-fits-all”, the schooling system would suit the people concerned far less. Therefore, we believe that Swiss education is always adapting itself to the community’s needs, which can be considered as the most important factor when looking for a model for multilingual education. We therefore believe that the growing demand of bilingual education in Switzerland shows the importance of acquiring a second language in the eyes of the population. Many of the current programmes are optional but promoted. Despite their optional nature, their popularity is continually increasing among students. Although secondary and tertiary school programmes seem to be successful, one could implement even more bi-/multilingual programmes at a young age, especially in bilingual regions, in order to facilitate language acquisition and allow earlier interaction between different speakers. Moreover, it is important to mention the rise in popularity of English. English was taken up as a subject in schools because parents and students saw the need for English economically. Schools quickly adopted the learning of English into their curricula (Stotz 2006). Some German-speaking cantons, such as Zurich, have even decided to teach English to children from the first year of primary school (ages 6 to 7). English is thus taught before French. Therefore, Stotz (2006) wonders how Swiss education will look like in a few years: with more and more students requiring English before any national language, national languages might soon not be considered worth learning anymore.

A limitation of this paper is that most of the extensive data on this subject is over a decade old and offers only a glimpse into the current situation. We assume that many policies and programmes have changed and grown and that more and more schools have adopted the approach of a multilingual education. In addition, the place of English as a potential lingua franca may also have evolved and be more significant than described. It could therefore be interesting to investigate the learning of English to the detriment of the national languages and its increasing presence in Switzerland.

References:

Brohy, C. 2008. “Und dann fliesst es wie ein Fluss…“: l’enseignement bilingue au niveau tertiaire en Suisse. Synergies: pays germanophones. 1, 51-66.

Elmiger, D. 2006. Deux langues à l’école primaire: un défi pour l’école romande, avec la collaboration de Marie-Nicole Bossart. Neuchâtel: Institut de recherche et de documentation pédagogique.

Elmiger, D. 2008. Die zweisprachige Maturität in der Schweiz: die variantenreiche Umsetzung einer bildungspolitischen Innovation. Schriftenreihe SBF.

García, O. 2009. Bilingual education in the 21st century: a global perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Grin, F. and Schwob, I. 2002. Bilingual Education and Linguistic Governance: The Swiss experience. Intercultural Education, 13:4, 409-426.

Lys, I. and Gieruc G. 2005. Etude de la maturité bilingue dans le canton de Vaud: Enjeux, outils d’évaluation et niveaux de compétence. Lausanne: Unité de recherche pour le pilotage des systèmes pédagogiques. 1-176.

Meune, M. 2010. La mosaïque suisse: les représentations de la territorialité et du plurilinguisme dans les cantons bilingues. Politique et Sociétés 29.1, 115–143.

Paternostro, R. 2016. Enseigner les langues dans des contextes plurilingues: réflexions socio-didactiques sur le français en Suisse italienne. Congrès Mondial de Linguistique Française. DOI: https://doi.10.1051/shsconf/20162707012

Stotz, D. 2006. Breaching the Peace: Struggles around Multilingualism in Switzerland. Language Policy. https://doi.10.1007/s10993-006-9025-4

Zimmermann, M. 2019. Prophesying success in the higher education system of multilingual Switzerland. Multilingua2020; 39.3, 299–320

Zimmermann, M. and Häfliger, A. 2019. Between the plurilingual paradigm and monolingual ideologies in the compulsory education system of multilingual Switzerland. Sección Monográfica. Lenguaje y Textos, 49, 55-66

Websites:

Canton du Valais, Kanton Wallis. 2006. Concept cantonal de l’enseignement des langues pour la pré-scolarité et la scolarité obligatoire. Département de l’éducation, de la culture et du sport, service de l’enseignement, Department für Erziehung, Kultur und Sport, Dienstelle für Unterrichtswesen. Available at: https://www.vs.ch/documents/212242/1231591/Concept+cantonal+de+l%27enseignement+des+langues.pdf/c8928ad0-678f-42f6-977c-43e1e4a1d07e. Accessed on: 13.12.2020.

Canton du Valais/Kanton Wallis. 2016. Le collège: la porte ouverte à toutes les professions du niveau supérieur. Available at: https://www.colleges-valaisans.ch/data/documents/Colleges-Valaisans/brochure_maturite_gymnasiale.pdf. Accessed on: 13.12.2020.

Etat de Fribourg/Staat Freiburg. 2020. Bilinguisme dans les écoles du secondaire supérieur et échanges linguistiques. Available at: https://www.fr.ch/formation-et-ecoles/ecoles-secondaires-superieures/bilinguisme-dans-les-ecoles-du-secondaire-superieur-et-echanges-linguistiques. Accessed on: 13.12.2020.

Illustrations:

Figure 1: White B. 2017. Ben White Photography. Available at: https://unsplash.com/photos/qDY9ahp0Mto. Accessed on: 20.12.2020.

Figure 2: Zanoli, M. 2006. Map Languages CH. Available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/. Accessed on: 20.12.2020.

Figure 3: centvues. 2012. Quelque chose a changé, en notre… Available at: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/ce8d781e-d05b-4598-b7e3-5b4acfc80c0c. Accessed on: 22.12.2020.

Figure 4: Serge1958. 2020. Switzerland trilingual and bilingual. Available at https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/94de9b9d-1e99-4f20-b5fa-8d1663ab4622. Accessed on: 22.12.2020.

Further Resources:

Elmiger D. 2020. Inventar des zweisprachigen Unterrichts in der Schweiz / Inventaire de l’enseignement bilingue en Suisse. Université de Genève.

Gohard-Radenkovic A. 2013. Radiographie de l’immersion dans l’enseignement supérieur en Suisse et à l’Université de Fribourg: les pré-requis nécessaires. French immersion at the University level. Vol. 6, 3-19

Langfocus. 2016. Languages of Switzerland – A Polyglot Paradise? Youtube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7p8GgX_hWyA. Accessed on: 20.12.2020

Le Pape Racine C., & Ross K. (2015). Code-Switching als Kommunikationsstrategie im reziprok-immersiven Unterricht an der Filière bilingue (FiBi) in Biel/Bienne (Schweiz) und didaktische Empfehlungen. Journal of Elementary Education, 8(1/2), 93-112.

Schoch, B. 2007. Lernen von den Eidgenossen? Die Schweiz – Vorbild oder Sonderfall? Osteuropa, 57, 27-46

The paradox of societal exploitation and unawareness of migrants’ multilingualism in Switzerland

Lina Junctorius

As multilingualism gains importance in the globalized word and migration becomes more frequent, new challenges arise for host societies in Europe. In Switzerland, migrants are at a disadvantage on the labour market if they are not fluent in the local languages. They therefore mostly have job positions that are rather invisible, and not well compensated. Their skills in non-local languages are not officially recognized. Simultaneously, migrant employees’ language skills are exploited by the companies to increase their efficiency and simplify the daily work life. Official unemployment institutions often choose to minimize costs instead of investing in migrant’s language learning. This leads to the discrimination of migrants as it limits their social mobility through professional chances. Switzerland and individual workplaces need to introduce strategies that handle the issues in the reviewed studies.

Keywords: Racism – Linguistic Discrimination – Swiss Labour Market – Immigration – Multilingualism

Switzerland, migration and language

In September 2020, Switzerland held a referendum about the free movement of people. The right-wing party, Swiss People’s party (SVP), tried to limit the immigration of non-national people. They argued that too many people immigrate to Switzerland. The referendum was rejected by 61.7% of the voters. It was not the first attempt of the SVP to limit the free movement of people. (Henley, 2020) The referendums are the result of the increase in migration related to the ongoing globalisation.